Why Problem–Solution Fit Isn’t Enough When Commercialising Telehealth in Africa: Who Pays Matters — Cost Trumps Everything

Many African telehealth startups nail problem–solution fit but fail to scale because they ignore the payer: who will actually pay for the service? This article explains why identifying payers (governments, insurers, employers, donors, patients) and designing around cost constraints is more important than technical fit alone. It provides evidence from Africa on out-of-pocket spending, willingness-to-pay, and successful business models; practical pricing and payer-engagement strategies; and actionable “hacks” to improve commercial viability. Policy, procurement, and mobile-payments lessons are included to help founders build sustainable telehealth ventures that people can and will pay for.

Abstract

Many telehealth and telemedicine startups in Africa correctly achieve problem–solution fit (a clear health problem and a working technical solution) but still fail to scale. This paper argues that problem–solution fit is necessary but not sufficient: the critical determinant of commercial success is payer fit — identifying who will pay and whether the price point is affordable in the target financing ecosystem. In the African context, health financing is dominated by high out-of-pocket (OOP) spending, low insurance penetration, and fragmented public procurement — factors that shape demand elasticity and willingness to pay (WTP). Drawing on systematic evidence and case studies from across the continent, this article outlines practical strategies (payer segmentation, B2B/B2B2C models, mobile-money integration, value-for-payer ROI studies, blended finance and donor partnerships), tactical “hacks” for early traction (channel partnerships, per-visit micro-pricing, employer bundles), and research methods (WTP surveys, discrete-choice experiments, cost-effectiveness analysis) founders must use. The paper concludes with an actionable checklist for founders and policy implications for health system actors seeking to scale digital health sustainably.

Keywords: telehealth, telemedicine, payer strategy, pricing, health financing, Africa, willingness to pay, business model

Introduction

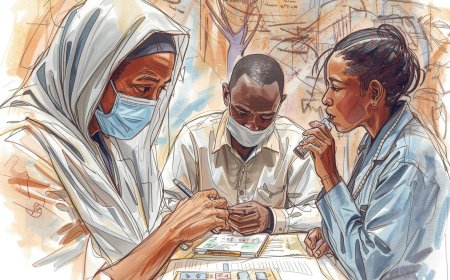

Problem–solution fit (PSF) — proving that your product solves an identified user problem — is the early milestone every founder celebrates. In telehealth, PSF often involves validating remote consultations, triage algorithms, or remote monitoring with clinicians and patients. Yet across Africa, many promising pilots stall at scale because no one is willing or able to pay the recurring costs of delivery, or because the chosen buyer (the end user) is not the real purchaser. In short: PSF gets you to product viability; payer fit gets you to commercial viability.

Three high-level features of the African context shape why payer considerations dominate commercialization outcomes: (1) high incidence of out-of-pocket health spending, (2) low and variable willingness to pay for private telehealth at prevailing prices, and (3) institutional purchasing (governments, insurers, donors, employers) that prefers demonstrable cost-savings or integration into existing payment channels. These features mean founders must design price and payment flows as core features of the product, not afterthoughts. WHO | Regional Office for Africa+2ScienceDirect+2

Evidence that Who Pays — and Cost — Drive Scale

Out-of-pocket spending is high and shapes demand elasticity

In the WHO African Region the average share of health expenditure financed from out-of-pocket payments remains high (well above recommended thresholds), which means most consumers in many countries pay directly for care and are sensitive to price. High OOP exposes households to catastrophic spending and makes them highly price-sensitive for discretionary services such as private teleconsultations. This reality constrains the price ceilings for direct-to-consumer (B2C) telehealth models. WHO | Regional Office for Africa+1

Willingness to pay (WTP) for telemedicine is variable and often limited

Multiple studies across African settings report wide ranges in WTP for telemedicine services: some populations show interest, but the proportion willing to pay and the amounts they will pay vary by country, income, age, and perceived risk. Reported WTP in several studies is modest (single-digit to low double-digit USD per consultation), and surveys often find only a minority willing to pay prevailing market rates for private teleconsultations. Startups that priced at “western” telehealth rates frequently discovered demand cliffs. PMC+2PMC+2

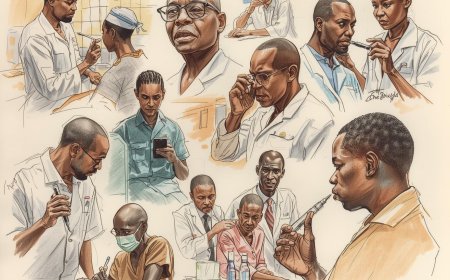

Sustainable telehealth business models in Africa tend to be B2B, B2B2C or hybrid

Recent literature and field reviews (including 2024–2025 studies) identify B2B (selling to employers, insurers, clinics), B2B2C (selling through payers who then offer services to consumers), and on-demand or subscription hybrids as more sustainable than pure B2C in many African markets. These models address the payment problem by targeting third-party payers who can internalize value (reduced absenteeism, lower referral costs) or aggregate many small users into a single payer. PMC+1

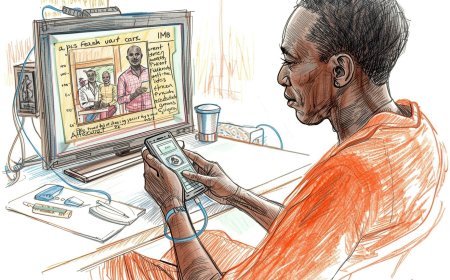

Mobile money and health wallets materially reduce friction — but do not replace payer engagement

Integration with mobile-money (e.g., M-Pesa) and health wallets reduces transaction costs and improves collection for micro-payments; such integrations have enabled programs to collect patient payments and to manage provider reimbursements more smoothly. However, mobile payments lower friction — they do not solve an affordability problem when willingness or ability to pay is absent. Thus payment rails are necessary but not sufficient without payer alignment. Tech In Africa+1

Procurement, insurance, and donor partnerships determine scale opportunities

Public procurement cycles, insurer formularies, and donor financing determine when and how digital health services get reimbursed at scale. Many pilots succeed clinically but fail to secure procurement or insurer reimbursement because they do not demonstrate payer-relevant outcomes (cost savings per patient, reductions in referrals, improved adherence). Bridging the “buyer–user” gap is essential: users may like the product, but buyers fund procurement decisions. digitalhealth-africa.org+1

What Founders Must Do: Strategy, Tactics, and “Hacks”

1. Start with a payer map — not only a user persona

Create a payer map that lists every plausible buyer: direct patients (B2C), employers, private insurers, national health insurance schemes, county/provincial health departments, NGOs/donors, pharmacies, and clinics. For each payer, document: (a) decision drivers (cost savings, quality, political priorities), (b) procurement cadence, (c) payment capacity, and (d) key contacts. Allocate product/market fit experiments to the payer with the fastest path to payment. irff.undp.org

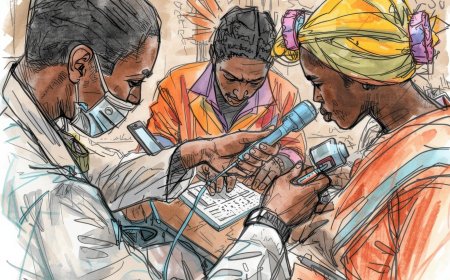

2. Use B2B/B2B2C pilots to overcome low WTP for direct consumers

Sell initial pilots to employers (occupational health), insurers (risk-sharing), or large clinics (provider efficiency). Employers and insurers can pay predictable per-employee/per-member fees and capture value (fewer sick days, lower referral costs). B2B contracts reduce CAC (customer acquisition cost) per paying user and stabilize revenue while you prove ROI. PMC+1

3. Make pricing a product decision — embed flexible, transparent pricing flows

Design tiered pricing (basic—teletriage, premium—video consult + meds delivery), micro-pricing for single sessions, and monthly subscriptions. Use tokenized payments or health-wallet top-ups for micropayments. Offer “pay-as-you-go” with clear caps and subsidies for low-income segments through cross-subsidization. Integrate billing and e-receipts to facilitate insurer reimbursement. Tech In Africa

4. Measure payer-relevant outcomes and build a simple ROI case

Track metrics that matter to payers: reduction in hospital referrals, average cost per episode, time saved per clinician, reduction in absenteeism for employers, and adherence improvements. Convert operational gains into monetary terms in a 12- or 24-month ROI model you can present during procurement. Payers buy demonstrated savings more readily than promises of “better care.” digitalhealth-africa.org

5. Use evidence-light “hacks” to demonstrate value fast

— Run time-motion studies in a single clinic to estimate consultation and referral reductions.

— Offer risk-sharing pilots (e.g., “you pay only if we reduce referrals by X%”).

— Bundle services with pharmacies or labs to create revenue share models.

— Offer to pilot at no upfront cost and use usage-based billing after month 3 if target metrics are met. These low-friction contracts often unlock procurement conversations faster than long tenders. PMC+1

6. Use rigorous pricing research before you set prices

Conduct discrete-choice experiments or WTP surveys in your target geographies to estimate elasticities and segment customers by price sensitivity. Pair WTP studies with costing exercises (provider cost per consult) to find break-even and subsidy needs. Many African studies show WTP is context-specific — do your homework locally. PMC+1

7. Design for the payment rails that exist — mobile money, health wallets, insurance gateways

Integrate M-Pesa, MTN Mobile Money, Airtel Money and local insurance APIs where available. Provide invoicing formats insurers require (diagnosis codes, clinician IDs). Work with local payment aggregators to reduce transaction fees and support reconciliations. Mobile-money lowers friction but align with payers for subsidized models. Tech In Africa+1

8. Consider blended financing and subsidized rollout for equity and scale

Donors and development partners often fund early scale where private payer markets are thin. Consider staged models: donor-subsidized rollout to prove impact, followed by transition to insurer/employer payment. Be transparent about transition timelines to avoid sustainability cliffs when subsidies end. irff.undp.org

Research & Evidence: How to Structure Your Internal Evaluation

-

Willingness-to-Pay (WTP) Study — sample n by region; use contingent valuation and discrete choice; report median WTP and proportions willing to pay at target price points. PMC+1

-

Costing Analysis — micro-cost the service (clinician time, platform costs, transaction fees, logistics); compute marginal cost per consult and break-even price given CAC. PMC

-

Pilot ROI Study — randomized or matched pilot with measured outcomes (referrals, admissions avoided, absenteeism); convert to monetary value for targeted payer. PMC

-

Procurement Readiness Checklist — legal, data protection, invoicing, clinician credentialing, local tax/compliance; required for insurer/government contracts. digitalhealth-africa.org

Quick Checklist for Founders (Actionable)

-

Build a payer map and rank by speed to revenue.

-

Run local WTP studies before setting consumer prices.

-

Prioritize B2B/B2B2C pilots (employers, insurers, clinics).

-

Integrate mobile money and insurer billing APIs from day one.

-

Offer short, metric-linked pilots (90–180 days) to buyers.

-

Prepare a 12-month ROI that converts clinical outcomes into cost reductions.

-

Plan staged financing (donor → payer transition) if consumer payments are insufficient. PMC+2Tech In Africa+2

Policy and Systemic Implications

For governments and insurers: supporting interoperability, publishing clear reimbursement rules for telehealth, and integrating digital health in essential benefits can unlock private innovation. For donors: targeted transitional financing that conditions scale on measurable payer adoption reduces the risk of unsustainable pilots. For regulators: transparent standards for telehealth invoicing and data exchange lower transaction costs for payers and suppliers alike. PMC+1

Conclusion

Problem–solution fit is an important early milestone for telehealth startups, but in Africa it is not sufficient for commercial scaling. The overriding question founders must answer is: who will pay, and at what price? High out-of-pocket spending, variable willingness to pay, and payer procurement dynamics mean that cost considerations must be designed into the product, business model, and go-to-market strategy from day one. Founders who treat pricing, payer engagement, and measurable ROI as core product features — and who choose the right payer channels (B2B/B2B2C, insurers, employers, donors) — stand the best chance of moving from promising pilots to sustainable scale.

References

Adzakpah, G., et al. (2023). Determining patients’ willingness to pay for telemedicine services and associated factors amidst fear of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Ghana. [Article]. PMC

Agbeyangi, A. O., et al. (2025). Telemedicine adoption and prospects in sub-Saharan Africa. [Article]. PMC

Arize, I., et al. (2017). Acceptability and willingness to pay for telemedicine. Journal/Report. PMC

Digital Health Africa. (n.d.). Understanding the buyer–user gap in digital health: Why great innovations struggle to scale in Africa. Digital Health Africa. digitalhealth-africa.org

Irihamye, E., et al. (2025). Sustainable by design: Digital health business models for telemedicine in Africa. ScienceDirect / Journal. ScienceDirect

Naggirinya, A. B., et al. (2025). Enablers, obstacles, value chain and business models for digital health in Africa. [PMC article]. PMC

Segun-Omosehin, O. A., et al. (2025). Evaluating the digital health technology landscape in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature / Communications Medicine. Nature

UNDP / IRFF. (2024). Insurance and telemedicine in Africa: case studies and partnership models. Report. irff.undp.org

World Health Organization, African Region. (2023). WHO African Region health expenditure atlas 2023. WHO | Regional Office for Africa

World Bank. (2023). Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure). World Bank Data. World Bank Open Data

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0