The Bedside-to-Business Pipeline: Leveraging Frontline Health Worker Innovation in Sub-Saharan Africa

A strategic framework for transforming the clinical insights of Sub-Saharan Africa's Frontline Health Workers into sustainable, profitable, and impactful MedTech ventures. It outlines the necessity of Human-Centered Design, Frugal Innovation, specialized patient capital, and systemic policy reform (e.g., WHO ML3 status and the Tanzania maintenance model) for successful scaling.

Executive Summary: The Bedside-to-Business Pipeline

The Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) healthcare landscape is defined by profound infrastructure constraints and a complex tapestry of localized disease burdens. Within this challenging environment, Frontline Health Workers (FLHWs), including Community Health Workers, nurses, and clinical officers, represent the continent’s most valuable, yet often underutilized, resource for innovation. These workers, who operate at the nexus of clinical care and community life, possess unique, granular "bedside insights" that can transform healthcare delivery.

This report establishes a strategic framework—the "Bedside-to-Business Pipeline"—designed to translate these grassroots observations into commercial ventures that are simultaneously lifesaving, profitable, sustainable, and impactful. The strategy requires a fundamental shift away from the reliance on imported, capital-intensive solutions towards locally derived, frugal innovations validated through Human-Centered Design (HCD).

The success of this pipeline hinges on three systemic interventions: first, the institutionalization of FLHWs as co-designers and essential distributors; second, the strategic deployment of patient capital and specialized incubation to de-risk market entry; and third, radical policy reform focused on regulatory harmonization (e.g., achieving WHO ML3 status) and integrated biomedical maintenance infrastructure, modeled on successful regional efforts like the one implemented in Tanzania. By prioritizing endogenous capacity building—from local rapid prototyping to the training of biomedical engineers—SSA can build resilient health ecosystems capable of attracting sustained follow-on investment and delivering widespread public health benefits.

I. Defining the Opportunity: The Strategic Value of Frontline Insights

The strategic imperative for localized health innovation in Sub-Saharan Africa is clear: imported medical technologies frequently fail due to their lack of congruence with local infrastructure, resource availability, and socio-cultural context. The solution lies in systematically harnessing the tacit knowledge held by the region’s frontline health workforce.

A. The Unique Role of Frontline Health Workers (FLHWs) as Innovators

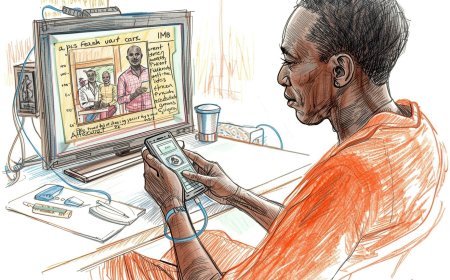

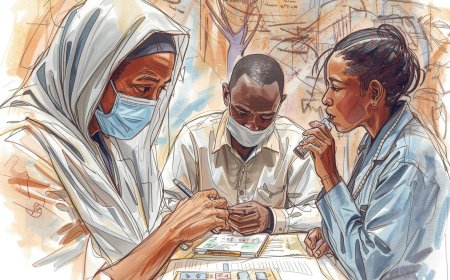

Frontline Health Workers are defined as frontline public health workers who are trusted members of, and possess an unusually close understanding of, the communities they serve.1 This intimate relationship allows the worker to serve as a liaison, link, or intermediary between formal health and social services and the community, facilitating access to necessary care.1

The Trust Dividend and De-risked Adoption

In many areas of SSA, particularly among historically marginalized groups, there is a deeply rooted distrust of external or formal medical systems, often stemming from historical and ongoing barriers to high-quality care.2 When trained members of the community, such as FLHWs, serve as advocates who counsel and support hesitant individuals to seek necessary medical care, they act as powerful agents for change.2

This role of trusted advocate represents an invaluable, non-financial asset that de-risks market adoption for locally created innovations. An intervention co-created with and delivered through an FLHW inherits a crucial level of community credibility. This substantially lowers the adoption barrier typically faced by foreign or 'top-down' health initiatives, thereby accelerating market entry and scaling potential. Moreover, programs utilizing Community Health Workers have been proven to increase quality of life, improve health outcomes, and significantly reduce hospitalizations and the overall cost of care.2

The Bedside Insight as the Core Asset

The daily operational experience of FLHWs provides an unparalleled dataset of "bedside insights." This includes firsthand knowledge of clinical pain points, logistical failure modes, infrastructural limitations (e.g., poor cold chain management, unreliable electricity), and deep cultural barriers that sophisticated, imported technologies often fail to recognize or address. Leveraging this source of viable problem definition is the foundational step in developing solutions that achieve high-impact outcomes.

B. Mapping Clinical Pain Points to Market Needs

To ensure commercial ventures are both financially viable and strategically meaningful, innovation must be rigorously mapped against the dual imperatives of regional disease burden and the core tenets of business sustainability.

Targeting Regional Disease Burdens

Innovation should align with the most prevalent regional healthcare challenges. An analysis of current medical device clinical trials across Africa indicates distinct regional focuses.3 For example, device trials related to Malaria, HIV, and male circumcision are predominantly conducted in Eastern and Southern Africa.3 Conversely, trials related to dental issues, fertility, and obesity tend to be concentrated in Northern Africa.3 FLHW-led ventures must ensure their solution addresses a well-defined, region-specific clinical gap with significant patient volume.

Conceptualizing Multidimensional Success

Successful SSA health ventures must satisfy a multidimensional definition of success that goes beyond mere clinical efficacy:

-

Lifesaving and Impactful: The innovation must directly address high-burden issues by increasing access and efficacy. An example is the mScan team in Uganda, whose devices are being used in medical clinics to scan pregnant women, with a goal of training frontline health workers to reach 1,000 women.4 This demonstrates a direct link between technology, FLHW training, and critical maternal health outcomes.

-

Profitable: The venture must generate sufficient, predictable revenue. This is necessary not only to cover operating expenses but also to support local manufacturing, provide salaries for FLHWs, and, crucially, attract the necessary follow-on funding from impact and venture capital investors.5 High-end medical technology is capital intensive, and while initial investors may view LDCs as risky, proven profitability is the ultimate de-risking mechanism.7

-

Sustainable: Sustainability demands integrated operating models that prioritize local capacity and maintenance over reliance on costly imported spare parts or external technicians. The Tanzanian model for integrated medical device management serves as a crucial blueprint for this (discussed further in Section III).8

The Policy Requirement for Long-Term Viability

The analysis of successful FLHW models outside of SSA demonstrates a pattern: broad implementation and financial sustainability become within reach only when policy shifts occur. For instance, in the United States, a recent ruling from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, effective January 1, 2024, allowed for Medicare reimbursement of services provided by community health workers.2 This ruling provided a clear and consistent funding channel, representing a paradigm shift away from varied, temporary funding sources such as federal, state, and foundation grants.2

This pattern strongly suggests that SSA governments must formalize and integrate the FLHW role into national health and reimbursement structures. For profitability models to be truly viable and scalable in the long term, the FLHW must transition from being supported primarily by philanthropic grants to being a recognized, financially supported professional partner in the healthcare system, backed by consistent policy.

II. Phase 1: Contextual Innovation and Insight Validation

The transition from a raw bedside observation to a commercially viable Minimum Viable Product (MVP) requires specialized design methodologies that inherently account for resource scarcity and cultural nuance.

A. The Frugal Design Mandate

Frugal innovation is not simply about cheapening a product; it is a systematic approach to value creation in resource-constrained environments. A frugal innovation in healthcare achieves an optimal balance and combination of cost, functionality, and performance dimensions based on the applied technology.10

Core Principles and Strategic Objectives

Frugal innovations prioritize low-cost interventions while vigorously maintaining efficacy, accessibility, and scalability.11 For FLHW-led ventures, the strategic objectives of frugality are typically threefold:

-

Providing Service in Unserved Areas: Reaching populations with no prior access to a specific health service.

-

Offering a Better or More Suitable Service: Improving care quality in poorly served areas.

-

Offering an Additional Service: Competing with conventional solutions in already well-served regions by offering superior accessibility or lower cost.10

For grassroots innovation in SSA, the primary focus must be on the first two objectives, maximizing social impact and market penetration where established solutions fail to reach.

Frugality as a Global Value Proposition

While born out of necessity in low-income countries, frugal innovations hold immense promise for reducing healthcare costs and addressing disparities globally.11 The strategic implication of this is profound: innovations designed under SSA constraints, where cost and resource efficiency are paramount, can be adopted in higher-resource settings seeking to manage the rising costs of care.10 This elevates the SSA innovator's value proposition, positioning their venture not just as a solution for local poverty, but as a disruptive, globally scalable model for cost reduction. This broadening of the addressable market dramatically expands the potential investor pool beyond dedicated impact funds to general venture capital seeking disruptive, cost-saving technologies.

It is also crucial to note that many previous high-profile healthcare innovations failed because their models rewarded inconsistent participation in primary care and preventive services.12 Frugal design, by its very nature, demands high accessibility and resource appropriateness, thereby encouraging the consistent use required for better patient outcomes and systemic sustainability.

B. Human-Centered Design (HCD) in SSA Healthcare

Human-Centered Design (HCD) is the indispensable methodology for ensuring that a frugal idea achieves genuine Product-Market Fit (PMF). A lack of PMF is consistently cited as a top reason for startup failure across Africa.6 HCD serves as the core de-risking mechanism against this failure point by embedding user empathy and cultural context into the development cycle.

Prioritizing Empathy and Co-Creation

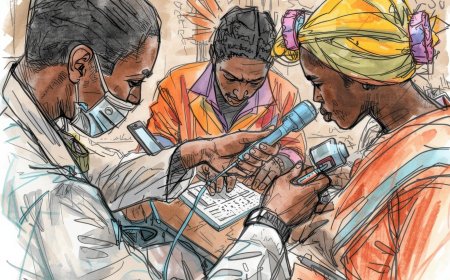

HCD begins by prioritizing empathy, which involves deeply understanding the lived experiences, challenges, and aspirations of the target population.14 This ensures that the resulting innovation addresses the root causes of health problems, rather than merely treating surface symptoms imposed by external perspectives.14 The process mandates engaging key stakeholders—including FLHWs, community leaders, and policymakers—in a collaborative design process to develop interventions that are culturally relevant, accessible, and truly reflective of local needs.14

For instance, programs utilizing HCD in East Africa have focused on rapid iteration and testing of interventions to strengthen a compassionate organizational culture within community health organizations.15 This collaborative approach transforms the FLHW from a user into a co-creator, ensuring that solutions are fit for purpose and operationally feasible within their daily work context.

C. Frameworks for Context Adaptation and Risk Communication

Innovators in low-resource settings must adopt frameworks that explicitly guide designers toward gaining a better understanding of the context of use.16 This formal contextual validation is essential for both technical development and investor relations.

Explicitly Addressing Infrastructural Gaps

Resource-limited settings present unique challenges related to infrastructure (e.g., unreliable power, poor logistics, limited connectivity). Specialized frameworks are necessary to prevent potential exploitation of research populations and the workforce in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) by adhering to existing ethical frameworks.17 Furthermore, these frameworks must include a mechanism for explicitly communicating potential infrastructural disadvantages to funders, sponsors, and auditors.17

This practice serves a critical dual function. Clinically, it informs the design of the device (e.g., maximizing battery life, ensuring robustness against dust). Commercially, it manages investor expectations regarding performance data collection and delivery mechanisms, protecting the venture from being judged unfairly against benchmarks derived from high-resource environments. By ensuring that the innovation includes "Context adaptation" as a core principle 17, the venture gains resilience.

Systemic Failure Attribution

A rigorous approach to HCD and Frugal design, which meticulously validates problem-solution fit, allows founders and investors to accurately assess the source of future scaling challenges. If a well-designed, context-adapted innovation falters, the cause is less likely to be attributed to an internal misstep, such as poor product-market fit or incorrect assessment of demand.13 Instead, failure can be attributed to external, systemic factors such as regulatory delays or overwhelming financial constraints.5 This accurate risk attribution is vital for guiding strategic action, allowing the ecosystem to focus lobbying and resource allocation efforts on addressing policy and financial hurdles, rather than wasting capital on unnecessary product tweaks.

III. Phase 2: Technical Development and Operational De-risking

The next phase moves from validated design principles to the creation of a physical or digital solution that is locally manufacturable, legally protected, and operationally resilient.

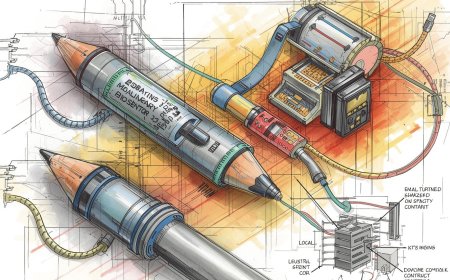

A. Prototyping and Local Manufacturing Capacity

In the medical device industry, the ability to prototype rapidly and accurately is pivotal for design validation and manufacturability.19 This capability allows developers to transform initial concepts into physical components that can be tested, refined, and validated, often within days.19

The Critical Prototyping Deficit

A significant bottleneck in SSA is the lack of robust, accessible rapid prototyping facilities. Without local rapid prototyping capacity, the iterative nature demanded by HCD and Frugal Design is severely compromised. The inability to quickly integrate feedback from FLHWs and clinicians delays timelines, increases development costs, and makes it challenging to optimize for Design-for-Manufacturability (DFM) using locally available materials and processes. This reliance on external prototyping services fundamentally undermines the principles of a localized, resource-appropriate innovation pipeline.

The strategic imperative, therefore, is the establishment of decentralized, hub-and-spoke rapid prototyping centers that can handle early iteration and precision component creation.19 These facilities are necessary to streamline development and ensure that products are optimized for performance and usability before committing to costly production tooling.19

B. Strengthening Biomedical Infrastructure (The Tanzania Model)

A locally-derived medical device, no matter how clever or frugal, becomes unusable if its maintenance and repair protocols fail in the field. Across many sub-Saharan African countries, medical device management systems are either weak or completely absent.8

Operational Sustainability and Tiered Maintenance

The Government of Tanzania’s decade-long plan (2011–2023) to improve medical device management systems, implemented through Swiss–Tanzanian cooperation, provides a definitive blueprint for operational sustainability.9 This integrated systems approach addressed personnel, maintenance facilities, documentation, and government policy.

Key successes included:

-

Capacity Building: Increasing the availability of biomedical engineers through new training courses and the establishment of permanent government positions.9

-

Infrastructure Development: Building additional district and regional maintenance and repair workshops, including a model regional referral biomedical equipment maintenance workshop in Dodoma.8

-

Structured Management: Establishing an integrated, tiered maintenance system supported by administrative tools (forms for reporting problems, job cards, equipment history cards).8

This tiered structure is critical for innovators:

|

Maintenance Level |

Tasks |

Maintenance Provider |

Proportion of Maintenance Tasks |

|

Level 1: User Maintenance |

Cleaning, careful handling, function, and pre-use test 21 |

All users in health-care facilities 21 |

60–80% 21 |

|

Level 2: Basic Maintenance |

Preventive maintenance, basic repairs, supervision, training, management 21 |

District health facility in-house maintenance units or private companies 21 |

10–25% 21 |

|

Level 3: Middle-level/Complex |

Complex and electronic repairs, very complex repairs, equipment overhaul 21 |

Regional government workshops and private companies 21 |

5–15% 21 |

Designing for the Maintenance Pyramid

The success of the Tanzania model, which substantially increased the percentage of functioning equipment and reduced costs by repairing rather than replacing 9, dictates that every FLHW innovation must integrate Level 1 maintenance training into its core offering and business model. Furthermore, the technical specifications (robustness, modularity, simplicity of components) must be engineered such that the device rarely requires Level 3, complex electronic repair. If an innovation requires Level 3 service too frequently, the business model becomes inherently unsustainable, given the relative scarcity and travel logistics associated with regional Level 3 workshops. The design philosophy must be dictated by the local maintenance infrastructure.

C. Intellectual Property (IP) and Technology Transfer

Innovation must be protected and its value leveraged to facilitate local manufacturing. While the lack of clear guidance related to Intellectual Property (IP) management is a reported challenge (15.46% of responses) 5, the core impediment is often the ability to execute the transfer of technology effectively.

The IP-Manufacturing Paradox

The system that moves research from the lab to real-world solutions—technology transfer—is critical for securing investment and realizing market potential.22 For SSA innovators, IP protection serves two roles: preventing international co-option and attracting local investment. However, the greater strategic priority is building the capacity for local production itself. Initiatives focusing on IP and technology transfer capacity for African medical manufacturing stakeholders are essential to help local manufacturers scale up production of essential health technologies.23 Fostering a sustainable medical innovation ecosystem requires empowering countries to produce their own health technologies and drive growth through knowledge and technology sharing.23

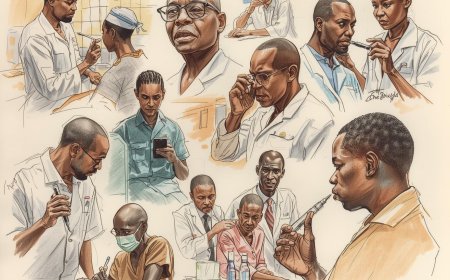

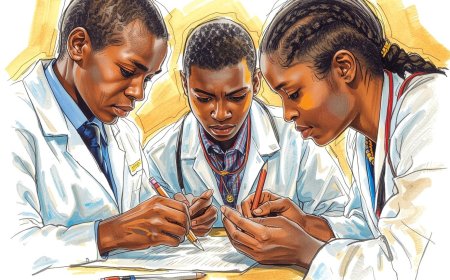

D. Addressing Human Resource Capacity

The scarcity of specialized personnel represents one of the most critical challenges to scaling health ventures in SSA. Insufficient human resource capacity is a major scaling hurdle, cited by 45.36% of respondents in one study.5 This challenge extends to the inability to entice the health workforce, particularly technically skilled workers, to stay and work in Africa.24

The Role of the Founding Team

For entrepreneurial ventures, this translates into high demands for the founding team structure. Successful incubation programs often mandate a multi-disciplinary team with at least one technical co-founder.6 Given that conflicts among founders are a leading cause of startup failure 13, investment must be strategically channeled not just into capital, but into technical training and mentorship. This addresses the dual problem of capacity shortage and founder stability, strengthening the venture's internal resilience against the failure point of a broken team.13

IV. Phase 3: Commercialization, Scaling, and Financial Viability

Transitioning from a de-risked prototype to a scalable, profitable business requires meticulous planning to overcome systemic market and financial obstacles.

A. Addressing Systemic Barriers to Scaling

African startups face unique struggles related to funding and infrastructure compared to their Western counterparts.18 Failures often result from a blend of external constraints and internal missteps, such as incorrectly assessing the size of the market, demand, or whether customers will pay for the product.18

Mitigating Premature Scaling

Expanding too quickly—premature scaling—is a significant risk, as it can overstretch resources and expose core weaknesses before stability is achieved in the primary market.13 This is why specialized incubation is vital. Villgro Africa, for instance, focuses on providing patient capital and customized support designed to de-risk ventures by helping innovators refine their solution and strengthen their business model before connecting them with major investors.6

Furthermore, building a startup in Africa demands exceptional persistence, as the journey is often characterized by long regulatory delays or resource depletion.13 Founders must set realistic expectations and engage with mentors and investors to stay motivated, recognizing that success stories often take years to unfold.13

B. Sustainable Business and Operating Models

Achieving profitability in a low-resource setting requires sophisticated, non-traditional commercial strategies focused on value delivery and operational efficiency.

1. Pricing Strategies for Low-Income Communities

Traditional cost-plus pricing models are often unfeasible. MedTech companies entering these markets often utilize competition-informed price practices.25 A particularly effective approach is Portfolio Pricing.26

Portfolio pricing leverages the overall value of a company’s product line to optimize revenue and capture market share. Lower-priced, high-volume items can build customer loyalty and drive volume sales, while higher-margin or subscription-based services increase overall profitability.26 This strategy allows for internal cross-subsidization, successfully aligning the profit motive with the mission to deliver affordable, high-impact care to low-income populations. However, this strategy requires sophisticated sales and marketing to communicate the value of the entire portfolio.26

2. Digitally Enabled and Flexible Operating Models

To overcome complexity and sustainably reduce operating expenses, healthcare leaders must adopt digitally enabled and flexible operating models.27 Digital solutions are essential for modernizing operations and improving organizational agility.27

A key aspect of this is the generation and commercialization of data. The implementation of electronic medical device management systems (as demonstrated in Tanzania) provides crucial data to health facilities and the health ministry regarding the operational status of devices, the need for repairs, and spare parts management.9 An FLHW venture that utilizes digitally enabled models can transform this necessary maintenance system into an additional, profitable revenue stream by offering predictive maintenance subscriptions or selling anonymized utilization data to government bodies and NGOs.

3. Distribution and Maintenance Strategies

FLHWs are not just users; they are core components of the distribution and maintenance model. The successful scaling of mScan, for example, relies on training frontline health workers to use their diagnostic devices in rural East Africa, integrating the FLHW directly into the service delivery chain.4 This ensures localized repair (Level 1 maintenance 21) and immediate technical support, which is often impossible via centralized models.

C. The Funding Landscape: Strategies for Securing Patient Capital

Financial constraints represent the most dominant and frequently cited challenge to scaling health innovations in SSA (88.66% of respondents).5 Given the view of LDCs as risky by traditional investors, specialized strategies are necessary to secure funding.

The Role of Impact Investors and Incubators

The primary entry point for FLHW-led ventures is through specialized incubators and impact investors. Organizations like Villgro Africa support emerging healthcare businesses, providing personalized incubation to help them effectively scale ideas and navigate the African startup ecosystem.6 They focus on patient capital, taking the necessary time to prepare companies for further investment by refining their solution and strengthening the business.6

This process follows a rigorous de-risking mechanism focusing on five key aspects: the team, the business model, investability, the product, and exit feasibility.6 The financial trajectory demonstrates the model's success: while Villgro Africa has deployed over $3.3 million in cumulative seed funding, this initial patient capital has unlocked over $49 million in subsequent follow-on funding.6 The seed funding acts as "de-risking capital," validating the team and business model and making the venture attractive for much larger growth-stage investment.

Entrepreneurs must also strategically leverage competitions and grants, such as the Frontline Health Worker Innovation Challenge, which awards seed funding (e.g., $50,000).28 Various funding calls and grants are continuously available for African healthcare entrepreneurs focusing on MedTech devices for Low and Middle Income Communities (LMICs).29

The following table summarizes the primary challenges and the required strategic interventions across the ecosystem:

Table 2: Financial and Capacity Gaps vs. Required Ecosystem Interventions

|

Identified Challenge Cluster |

Primary Impact on Scaling |

Prevalence/Key Metric |

Strategic Intervention Required |

|

Financial Constraints |

Limits R&D, manufacturing, and talent retention |

88.66% reported challenge 5 |

Patient capital, seed funding, and de-risking mechanisms (Incubators) 6 |

|

Human Resource Capacity |

Inability to entice health workforce, weak founding teams |

45.36% reported challenge 5 |

Customized technical support, specialized mentorship, and technical co-founder mandates 6 |

|

Regulatory Fragmentation |

Slows market entry and increases cost of compliance |

Country-by-country evaluation required 31 |

Regional harmonization efforts (COSECSA), acceleration to ML3 status, and specific policy guidance for digital health 32 |

|

Operational Sustainability (Maintenance) |

High costs from equipment failure and replacement |

Weak/Absent management systems pervasive in SSA 8 |

Integrated policy reform following the Tanzania model (tiered maintenance, biomedical engineer training) 9 |

V. Policy and Ecosystem Recommendations for Sustained Impact

The ability to scale grassroots innovations from the bedside to a pan-African business requires high-level systemic transformation, primarily driven by governments and regulatory bodies.

A. Harmonizing Regulatory Systems and Ensuring Quality

The lack of harmonized medical device regulations across SSA countries creates a significant obstacle to scaling. Current underdeveloped regulatory processes often necessitate a complex, country-by-country evaluation for new medical devices.31

The ML3 Imperative as Economic Policy

A stable and effective regulatory environment is fundamental for supporting local manufacturing and fostering trust. The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Benchmarking Tool (GBT) Maturity Level 3 (ML3) status signifies such a stable environment.32 The achievement of ML3 status by several African nations—including Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa—is a critical milestone.32

While ML3 status is primarily a public health benefit, reducing substandard and falsified medicines 32, its secondary effect is profound economic stimulation. A stable regulatory environment de-risks local manufacturing, which encourages companies to produce health technologies locally.23 This aligns directly with the "Profitable" and "Sustainable" goals of the pipeline by retaining capital, creating jobs, and improving national health resilience.

Actionable Regulatory Steps

Governments must accelerate the harmonization of regulatory systems, drawing lessons from existing regional bodies such as the College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa (COSECSA).31 Furthermore, given the rapid adoption of smartphones across SSA (expected to reach 65% of connections by 2025) 33, appropriate regulatory standards and guidance must be developed specifically for health applications and digital tools to facilitate the adoption of evidence-based, safe, and efficient digital health solutions.33

B. Government Policy Support and System Strengthening

Sustained political commitment and adequate resource allocation are prerequisites for strengthening national regulatory and management systems.32

Institutionalizing the Grassroots Input Loop

Following successful examples where government agencies solicit voluntary assistance from the public (crowdsourcing) to inform future policy and service decisions 34, SSA governments should establish formal mechanisms (e.g., innovation challenges or dedicated digital platforms) to obtain FLHW input on policy and service delivery challenges. This practice institutionalizes the "bedside insight" as an official data source for governance innovation, directly connecting grassroots clinical realities to high-level policy formulation.

Strategic Investment in Health Tech Hubs

Africa is rapidly emerging as a hub for disruptive health innovation, having attracted $550 million in investments between 2020 and 2023.35 Governments must make strategic policy decisions to leverage this traction, focusing on technologies associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), such as digital diagnostics and biotechnology.35 These targeted investments will deploy diagnostic tools more effectively, compensate for doctor shortages, and accelerate African-led health discoveries.35

C. A Strategic Roadmap for Stakeholders

The Bedside-to-Business Pipeline demands coordinated action from all ecosystem players:

The Bedside-to-Business Pipeline: Operationalizing FLHW Insights

|

Pipeline Phase |

Success Metric |

FLHW Role in Validation |

Ecosystem Enabler (Policy/Finance) |

|

Insight Generation |

Problem-Solution Fit 6 |

Identifying root causes and cultural barriers (HCD Empathy) 14 |

Government crowdsourcing of clinical pain points 34 |

|

Design & Prototyping |

Context Adaptation/Frugality 10 |

Field testing, usability feedback, and DFM input 19 |

Local rapid prototyping facilities; Technology Transfer Capacity 23 |

|

Commercial Scaling |

Profitability and Follow-on Funding 6 |

Training, distribution, and Level 1 maintenance provision 4 |

Impact Investor Seed Funding; Portfolio Pricing Models 6 |

|

Systemic Impact |

Policy Integration and Health Outcomes Improvement 2 |

Continuous data feedback via digital models 9 |

ML3 Regulatory Status; Formal FLHW Reimbursement Policy 2 |

Governments and Policymakers must prioritize regulatory harmonization (achieving and maintaining ML3 status) 32, invest in technology transfer and IP protection capacity 23, and make dedicated financial commitments to decentralized maintenance infrastructure (the Tanzania model).9

Investors (VC/Impact) must recognize the necessity of patient capital and customized incubation.6 Funding should be directed toward ventures demonstrating rigorous HCD and Frugal design validation, focusing on de-risking internal scaling challenges like human resource capacity and product-market fit.5

Academic Institutions and NGOs should partner with local innovation hubs to establish and manage rapid prototyping facilities.19 They must also develop standardized curricula to address the severe capacity constraint in technical roles, such as training biomedical engineers and technical co-founders.

Frontline Organizations and FLHWs must actively seek institutional support that aligns with standards development and policy.5 Their role in governance innovation and co-creation (HCD) 14 is paramount, ensuring that the innovation pipeline remains grounded in community needs.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The transformation of SSA healthcare through grassroots innovation is fundamentally an exercise in systems integration and strategic resource redirection. The evidence demonstrates that the most impactful and sustainable ventures are those that intentionally de-risk their solutions at every stage by leveraging the inherent advantages of the local context—chief among them, the intimate knowledge and trust held by the Frontline Health Worker.

A key conclusion derived from the systemic analysis is that success in SSA requires a philosophical shift away from models inherited from the colonial past, which often focused on the individual and relied on imported theories.24 By centering the innovation process on the FLHW, the ecosystem naturally pivots toward community-focused, population-based solutions, ensuring contextual relevance.

The primary strategic recommendation is the immediate and comprehensive adoption of the Integrated De-Risking Strategy (IDS):

-

Mandate HCD and Frugality: All early-stage healthcare investment and grant funding must be contingent upon documented HCD validation (proving Product-Market Fit with FLHWs) and adherence to Frugal Innovation principles (designing for cost, accessibility, and Level 1 user maintenance).10

-

Institutionalize Maintenance and Data Streams: Governments must adopt the integrated Tanzanian maintenance model, allocating human and financial resources to district and regional workshops.9 Innovators must incorporate digital tools that report device operational status, commercializing this data stream to create profitable, ongoing service and maintenance revenue.9

-

Deploy Patient De-Risking Capital: Impact investors must continue to expand specialized incubation programs, viewing initial seed capital not merely as investment, but as capacity-building and de-risking expenditure necessary to unlock larger follow-on funding, specifically targeting the internal challenges of human resource capacity and founding team stability.5

-

Accelerate Regulatory Harmonization (ML3 Focus): Policymakers must treat the achievement of WHO ML3 status and the establishment of local IP/technology transfer capacity as critical economic policy initiatives, essential for attracting capital and enabling local manufacturing.23

By executing this IDS framework, SSA can move beyond episodic, grant-funded projects to create self-sustaining, profitable, and systemically impactful health technology ventures driven by those who understand the local challenges best: the healthcare frontline.

Works cited

-

Community Health Workers in Rhode Island: Growing a public health workforce for a healthier state, accessed November 24, 2025, https://health.ri.gov/sites/g/files/xkgbur1006/files/publications/reports/CommunityHealthWorkersInRhodeIsland.pdf

-

These workers can be pivotal in improving U.S. health equity - Northwestern Now, accessed November 24, 2025, https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2024/03/community-members-can-be-key-partners-in-improving-u-s-health-equity

-

A compound analysis of medical device clinical trials registered in Africa on clinicaltrials.gov, accessed November 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11453074/

-

Meet the Healthcare Start-ups That Won the Africa Innovation ..., accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.jnj.com/innovation/meet-the-healthcare-start-ups-that-won-the-africa-innovation-challenge-2-0

-

Towards a Healthcare Innovation Scaling Framework—The Voice of the Innovator - PMC, accessed November 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9735727/

-

Villgro Africa | Supporting Emerging Healthcare Businesses, accessed November 24, 2025, https://villgroafrica.org/

-

Strengthening Medical Technology Innovation Ecosystems to address Non-communicable Diseases in Least Developed Countries - WIPO, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/web-publications/strengthening-medical-technology-innovation-ecosystems-to-address-non-communicable-diseases-in-least-developed-countries/assets/81778/strengthening-medical-technology-2025-en.pdf

-

Medical device management reform, United Republic of Tanzania - World Health Organization (WHO), accessed November 24, 2025, https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/bulletin/online-first/blt.23.290636.pdf?sfvrsn=9a00206_3

-

Medical device management reform, United Republic of Tanzania - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed November 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11362694/

-

Frugal Innovation for Point-of-Care Diagnostics Controlling Outbreaks and Epidemics | ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, accessed November 24, 2025, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01712

-

Frugal Innovations in Orthopaedics - PMC - PubMed Central - NIH, accessed November 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12446174/

-

3 Major Healthcare Innovations That Ultimately Failed ... And Why - Vera Whole Health, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.verawholehealth.com/blog/major-healthcare-innovations-that-ultimately-failed

-

Top 5 Reasons African Startups Fail —and How to Beat the Odds - Pitchwise, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.pitchwise.se/blog/top-5-reasons-african-startups-fail---and-how-to-beat-the-odds

-

Human Centered-Design (HCD): Creating public health innovations with the people and for the people, accessed November 24, 2025, https://designforhealth.cchub.africa/human-centered-design-hcd-creating-public-health-innovations-with-the-people-and-for-the-people/

-

Human Centered Design - The Task Force for Global Health, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.taskforce.org/face-human-centered-design/

-

(PDF) Towards A Framework for Holistic Contextual Design for Low-Resource Settings, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312475191_Towards_A_Framework_for_Holistic_Contextual_Design_for_Low-Resource_Settings

-

A qualitative study based on interviews with investigators, sponsors, and monitors conducting clinical trials in sub-Saharan Africa - Research journals - PLOS, accessed November 24, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010121

-

Why over 50% of Africa's startups might not survive, accessed November 24, 2025, https://techpoint.africa/insight/africas-startups-might-not-survive/

-

The Role of Rapid Prototyping in Medical Device Development, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.photofabrication.com/the-role-of-rapid-prototyping-in-medical-device-development/

-

Overcoming Challenges in Medical Prototype Development - Kritikal Solutions, accessed November 24, 2025, https://kritikalsolutions.com/medical-prototype-development/

-

(PDF) Medical device management reform, United Republic of Tanzania - ResearchGate, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383662555_Medical_device_management_reform_United_Republic_of_Tanzania

-

Comment: A two-fold threat to medical research and innovation, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.heraldnet.com/opinion/comment-a-two-fold-threat-to-medical-research-and-innovation/

-

IP and Tech Transfer Capacity for African Medical Manufacturing Stakeholders - WIPO, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/global-health/w/news/2025/ip-and-tech-transfer-capacity-for-african-medical-manufacturing-stakeholders

-

The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities - PMC, accessed November 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7123888/

-

(PDF) Price-Setting Strategies for Product Innovations in the Medtech Industry, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322960582_Price-Setting_Strategies_for_Product_Innovations_in_the_Medtech_Industry

-

Medtech pricing strategies & how to optimize yours - Definitive Healthcare, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.definitivehc.com/blog/medtech-pricing-strategies

-

Healthcare | SSA & Company, accessed November 24, 2025, https://ssaandco.com/capabilities/healthcare/

-

Frontline Health Worker Innovation Challenge Winners - Villgro Africa, accessed November 24, 2025, https://villgroafrica.org/frontline-health-worker-innovation-challenge/

-

Health Care Grants in Africa - Instrumentl, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.instrumentl.com/browse-grants/africa/health-care-grants

-

Funding Calls - Villgro Africa, accessed November 24, 2025, https://villgroafrica.org/news-events/funding-calls/

-

The Evolving Landscape of Medical Device Regulation in East, Central, and Southern Africa - Global Health: Science and Practice, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/ghsp/early/2021/03/24/GHSP-D-20-00578.full.pdf

-

Strengthening National Regulatory Authorities in Africa: A Critical Step Towards Enhancing Local Manufacturing of Vaccines and Health Products - NIH, accessed November 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12197664/

-

Regulatory standards and guidance for the use of health applications for self-management in Africa: scoping review protocol | BMJ Open, accessed November 24, 2025, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/12/2/e058067

-

Open Government Initiative | SSA, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.ssa.gov/open/

-

Health care in Africa: Emerging technologies at play - Brookings Institution, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/health-care-in-africa-emerging-technologies-at-play/

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0