Public–Private Partnerships in Kenya’s HealthTech Ecosystem: A Case Study of Teleconsultation Platforms; The Hits, the Misses, and the Opportunities Galore

Kenya’s health sector is rapidly digitising, with teleconsultation platforms emerging as a critical bridge between overstretched public systems and an innovative private HealthTech ecosystem. This secondary research paper examines how public–private partnerships (PPPs) are shaping teleconsultation in Kenya, focusing on regulatory reforms, flagship digital health initiatives, and leading platforms such as Sema Doc, Baobab Circle’s Afya Pap, MYDAWA, Penda Online and newer AI-driven telemedicine solutions. Drawing on policy documents, grey literature and industry reports, the paper unpacks “the hits” (access, efficiency, innovation), “the misses” (regulation, equity, business-model risk, data governance) and the “opportunities galore” as Kenya transitions from NHIF to SHIF and implements the Digital Health Act and related regulations. It concludes with actionable policy and investment recommendations for government, private innovators, development partners, and investors seeking to build a more inclusive, resilient and sustainable HealthTech ecosystem.

Abstract

Kenya’s health system is undergoing a profound digital transformation, driven by a combination of policy reforms, rising mobile connectivity and a dynamic private HealthTech ecosystem. Public–private partnerships (PPPs) increasingly sit at the heart of this transformation, particularly in the emerging teleconsultation market. This secondary research paper explores how PPPs are shaping Kenya’s HealthTech ecosystem through the lens of teleconsultation and related remote-care platforms. It synthesises evidence from national policy documents, grey literature, academic works and industry reports to answer three questions: (1) How are PPPs configured around teleconsultation platforms in Kenya? (2) What have been the major achievements (“hits”) and shortcomings (“misses”) of these PPPs? and (3) What opportunities exist to deepen and optimise PPPs for equitable, sustainable teleconsultation at scale?

The paper first outlines the broader policy and regulatory environment, including the Digital Health Act No. 15 of 2023, the E-Health Bill 2023 and draft digital health regulations that define and govern telemedicine and digital health data exchange.Keli Kenya+3Parliament of Kenya+3Ministry of Health Kenya+3 It then situates teleconsultation within Kenya’s mixed health system, where the private sector supplies around 45% of health goods, services and technologies and where PPPs are viewed as a key route to universal health coverage (UHC).DLA Piper Africa+1 Case examples—Sema Doc, Baobab Circle’s Afya Pap, MYDAWA, Penda Online, Hillgan Innovations, and PPP-enabled digital models such as Empower Health—illustrate how public actors, private innovators, telcos, banks, insurers and donors co-create digital care pathways.Medtronic LABS+9Sollay Kenyan Foundation+9Engineering For Change+9

“The hits” include expanded access in underserved areas, improved chronic-disease management, strengthened data-driven decision-making and new investment flows into HealthTech.Sauce+4VoiceOut+4Katani Hospital+4 “The misses” cluster around regulatory uncertainty, fragmented financing, the digital divide, concerns about data privacy, sustainability of business models and broader PPP governance challenges.Positive Voice of Kenya+7Katani Hospital+7VoiceOut+7 The paper argues that Kenya now stands at an inflection point: as NHIF transitions to the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) and digital health regulations are finalised, there is a unique opportunity to embed teleconsultation PPPs within an interoperable, rights-respecting, value-for-money UHC architecture.Parliament of Kenya+4KHF+4CR Advocates LLP |+4

The paper concludes with policy and practice recommendations, including aligning SHIF benefit packages with teleconsultation services, establishing PPP frameworks specific to digital health, strengthening data governance and cybersecurity, investing in last-mile connectivity, and incentivising evidence generation through real-world evaluations of teleconsultation PPPs.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background: Kenya’s health system and the rise of digital health

Kenya operates a mixed health system where public, private for-profit, faith-based and non-governmental providers all play significant roles. The private sector is especially prominent: by one estimate, private actors provide roughly 45% of health goods, services and technologies in the country, underpinned by a Ministry of Health Public–Private Collaboration Strategy that explicitly seeks to harness private capacity for public health goals.DLA Piper Africa

Despite this mix, systemic challenges persist: geographic inequities in service provision, a shortage and maldistribution of health workers, infrastructure gaps, and high out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure limit access to timely, quality care—particularly in rural and peri-urban areas.VoiceOut+1 Kenya’s commitment to universal health coverage (UHC) by 2030 has therefore driven a search for new service delivery and financing models that are scalable, sustainable and more efficient.

Digital health has emerged as a central pillar of this strategy. Kenya has seen a flourishing of electronic medical records, mHealth applications, health information systems, and telemedicine platforms that leverage the country’s relatively high mobile penetration to extend care beyond physical facilities.Keli Kenya+1 Teleconsultation—synchronous and asynchronous remote consultations via voice, SMS, chat or video—is one of the most visible and rapidly evolving components of this digital health landscape.kutrrh.go.ke+1

1.2 PPPs, HealthTech and teleconsultation

Public–private partnerships are broadly defined as long-term agreements between public authorities and private entities to design, finance, build, operate or deliver services, with shared risks and rewards. In Kenya’s health sector, PPPs have previously focused on infrastructure (e.g., the Medical Equipment Services programme), financing and specialized services.Ministry of Health Kenya+2IA Journals+2 Increasingly, however, PPPs are being used for digital health and HealthTech-enabled service delivery, including teleconsultation.

Teleconsultation platforms rely on a complex ecosystem: regulators, professional councils, national and county governments, mobile network operators (MNOs), banks, insurers, technology start-ups, NGOs and donors all interact to determine whether services are affordable, trusted and sustainable. Examples include Sema Doc’s collaboration with Safaricom, a bank and an insurer to bundle teleconsultation with health savings and loans; Baobab Circle’s Afya Pap, which partners with health providers and organisations to offer remote coaching and virtual consultations for chronic diseases; and MYDAWA, which integrates teleconsultation, telepharmacy and diagnostics through a digital-first model.Sauce+7GSMA+7Engineering For Change+7

These arrangements exemplify PPPs or PPP-like public–private collaboration, even when they are not branded as such in policy documents: public actors enable, regulate or co-finance services provided through private technology platforms, while the latter extend and modernise public health functions.

1.3 Policy transitions: Digital Health Act and SHIF

Kenya’s rapid digitalisation is being codified through a series of legal instruments. The E-Health Bill, 2023, sets out principles and structures for e-Health, including the establishment of telemedicine and mHealth systems and the registration of digital health providers.Parliament of Kenya The Digital Health Act No. 15 of 2023 and subsequent draft regulations from 2024 further outline governance for digital health data exchange, define “telemedicine health providers,” and stipulate licensing, interoperability and data protection requirements.Ministry of Health Kenya+2Ministry of Health Kenya+2

Parallel to this, Kenya is transitioning from the long-standing National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) to a new Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), administered by the Social Health Authority (SHA). This reform aims to improve risk pooling, benefit design and provider payment mechanisms in pursuit of UHC, with digital systems and robust data management seen as essential for effective reimbursement and fraud control.Medinous+3KHF+3Nation Africa+3

These two transitions—digital health regulation and SHIF—are intimately connected to teleconsultation PPPs. How teleconsultation services are licensed, reimbursed and integrated into public benefit packages will determine whether they remain niche services for the connected middle class or become core components of Kenya’s UHC infrastructure.

1.4 Objectives and research questions

This paper uses secondary research to map and critically analyse PPPs in Kenya’s teleconsultation space, guided by three questions:

-

Configuration: How are public–private partnerships around teleconsultation platforms structured and governed in Kenya’s HealthTech ecosystem?

-

Performance: What have been the main “hits” (successes) and “misses” (shortcomings) in terms of access, quality, equity, financial sustainability and system integration?

-

Future prospects: What “opportunities galore” exist to deepen and optimise PPPs for teleconsultation in light of ongoing policy and financing reforms?

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Background

2.1 Public–private partnerships in health

PPPs in health encompass a wide spectrum: from simple service contracts and management agreements to complex design–build–finance–operate arrangements and joint ventures. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Kenya, PPPs have been promoted as instruments to mobilise private capital, transfer technical expertise, share risk and enhance efficiency in settings where public resources and managerial capacity are constrained.Academia+1

However, the PPP literature also highlights common pitfalls: asymmetric information between public and private partners, weak contract management, lack of transparency, inequitable risk-sharing and the danger that PPPs prioritise commercially attractive services over public health needs.Academia+1 These tensions are particularly salient in digital health, where private platforms may scale rapidly while regulators and public purchasers struggle to keep pace.

2.2 Digital health and teleconsultation as ecosystem phenomena

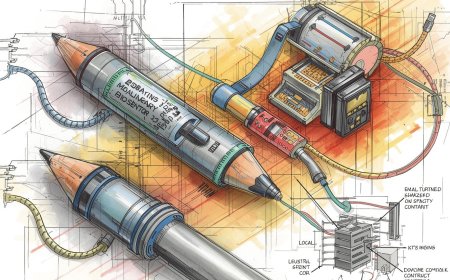

Digital health ecosystems are characterised by network effects, platform dynamics and data flows. Teleconsultation is not simply a single “product” but a composite of:

-

Digital interfaces (USSD, apps, web portals, call centres)

-

Connectivity infrastructure (mobile networks, broadband, devices)

-

Clinical and back-office systems (electronic health records, decision-support tools, logistics and payment systems)

-

Human resources (licensed clinicians, call centre agents, community health workers)

-

Data and analytics (clinical data, claims data, population health insights)

Telemedicine is generally defined as the use of telecommunication technologies to deliver medical services remotely, including consultations, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up.kutrrh.go.ke+1 Teleconsultation refers specifically to the remote interaction between a patient and clinician (or between clinicians) for assessment, advice and care planning.

In Kenya, teleconsultation often occurs through mobile-based channels—voice, SMS, chat and increasingly video—integrated with services such as e-prescriptions, lab referrals and medicine delivery.Hillgan Innovations+3MYDAWA+3Penda Health+3

2.3 Kenya’s digital health policy and regulatory landscape

Kenya’s policy frameworks increasingly recognise digital health as a strategic enabler. The Digital Health Bill and Act, together with draft regulations, aim to establish a coherent system for registration, accreditation and oversight of digital health providers, including telemedicine providers.Keli Kenya+3Parliament of Kenya+3Ministry of Health Kenya+3 Key features include:

-

Definition of telemedicine and mHealth systems as formal health service modalities

-

Roles for the Cabinet Secretary for Health and the Council of Governors in establishing e-health centres and telemedicine networks

-

Provisions on data protection, interoperability, consent and patient rights in digital health

-

Licensing and duties of e-health providers, including professional standards and quality of care requirements

A Regulatory Impact Statement prepared by the Ministry of Health underscores the intent to regulate digital health in alignment with national data protection laws and UHC goals, while recognising that telemedicine services were previously offered in a fragmented, largely unregulated manner.Ministry of Health Kenya+1

2.4 Health financing reforms: From NHIF to SHIF

The transition from NHIF to SHIF seeks to address longstanding criticisms of Kenya’s social health insurance, including limited coverage, inadequate benefits and administrative inefficiencies.Nation Africa+2CR Advocates LLP |+2 The Social Health Authority Act and related regulations envisage more comprehensive and progressive benefit packages, restructured contribution mechanisms and greater use of digital systems for enrolment, verification and claims management.KHF+1

For teleconsultation PPPs, the key questions are:

-

Will teleconsultation (and associated services such as e-prescriptions, home-based care and telemonitoring) be explicitly included in SHIF benefits?

-

How will reimbursement for teleconsultation be structured (fee-for-service, capitation, bundled payments, value-based models)?

-

How will digital health platforms integrate with SHIF’s data and claims infrastructure?

At present, teleconsultation platforms operate predominantly on out-of-pocket payments, employer/insurer-funded packages, donor-funded pilots or hybrid models, with limited systematic integration into national insurance schemes.Positive Voice of Kenya+3GSMA+3MYDAWA+3 This has significant implications for both equity and sustainability.

3. Methodology

This study employs a secondary research (desk review) design. No primary data were collected.

3.1 Data sources and search strategy

The review draws on four broad categories of sources:

-

Policy and legal documents from Kenyan government institutions, particularly the Ministry of Health, Parliament and the Social Health Authority (or its transition structures). Key documents include the E-Health Bill 2023, the Digital Health Act 2023 and associated draft regulations, as well as FAQs and guidance on the SHIF transition.Medinous+5Parliament of Kenya+5Ministry of Health Kenya+5

-

Grey literature (reports, briefs, NGO and think tank publications, law firm analyses) on PPPs, digital health and telemedicine in Kenya.Keli Kenya+3DLA Piper Africa+3Academia+3

-

Web content from Kenyan health facilities and HealthTech companies, including teleconsultation platforms such as MYDAWA, Penda Health, Baobab Circle/Afya Pap, Hillgan Innovations and others.Sauce+7MYDAWA+7Penda Health+7

-

Opinion and explainer pieces from Kenyan organisations and commentators discussing telemedicine’s role, opportunities and challenges in Kenya, as well as PPP case descriptions such as Sema Doc and Empower Health.Positive Voice of Kenya+7VoiceOut+7Katani Hospital+7

Search queries combined terms such as “Kenya telemedicine”, “teleconsultation platform Kenya”, “digital health PPP Kenya”, “Digital Health Bill 2023 Kenya”, “NHIF SHIF digital”, and “Sema Doc Baobab Circle MYDAWA Penda telemedicine”.

3.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included materials:

-

Focus on Kenya (or multi-country initiatives with substantial Kenyan components)

-

Address telemedicine/teleconsultation, digital health or PPPs in health

-

Published mainly between 2015 and 2025, with emphasis on more recent materials (post-2020) especially for regulatory and market developments

Excluded materials:

-

Purely clinical telemedicine research with little relevance to PPPs or platform governance

-

Opinion pieces without factual grounding or that duplicated more robust sources

Given the fast-moving nature of HealthTech, the review prioritised sources published or updated more recently, especially for market and regulatory developments.

3.3 Limitations

As a secondary research paper, this study is constrained by the availability, depth and quality of existing documentation. Some PPP arrangements and commercial details are not publicly documented, and many teleconsultation platforms remain understudied. The paper therefore interprets available evidence cautiously and indicates where inferences are being drawn. Moreover, “PPP” labels are not consistently applied across sources; in some cases, PPPs are implied through collaboration between public entities and private digital health providers rather than being formally designated as PPPs in legislation or contracts.

4. Overview of Kenya’s Teleconsultation Ecosystem and PPPs

4.1 Telemedicine and teleconsultation in Kenya: A snapshot

Over the past decade, Kenya has witnessed a steady rise in telemedicine initiatives. Early models included health hotlines and USSD-based services offering advice and basic triage; later evolutions incorporated real-time voice and video consultations, electronic prescriptions, and integration with pharmacies and labs.kutrrh.go.ke+2GSMA+2

Key drivers include:

-

High mobile phone penetration and growing smartphone adoption

-

Urban–rural disparities in the distribution of specialised health workers

-

Demand for convenient services from an increasingly digital-savvy population

-

Policy emphasis on UHC and digitalisation of government services

-

COVID-19, which accelerated acceptance of remote care modalities

Teleconsultation platforms now serve diverse segments: low-income and rural populations via USSD or basic phones, urban middle-class users via apps and web portals, chronic disease patients through telemonitoring and life coaching, and corporate or insured clients through employer–insurer packages.PharmAccess+5Baobab Circle+5Swiss Re Foundation+5

4.2 Public–private collaboration in digital health and teleconsultation

Kenya’s Ministry of Health has explicitly acknowledged the role of private sector actors in digital health and has developed strategies and legal instruments that envisage greater public–private collaboration.DLA Piper Africa+2Keli Kenya+2 This is complemented by PPPs such as:

-

Medical Equipment Services Programme, where private vendors supply, install and maintain diagnostic equipment (e.g., CT scans) under long-term contracts with public hospitals, paid per service delivered.Ministry of Health Kenya

-

Empower Health, a nationally scaled programme run by Medtronic LABS in partnership with the Ministry of Health and several counties, using digital tools, training and data analytics to power community-based chronic disease care.Medtronic LABS+1

-

Philips–Amref–Makueni County PPP, which modernises primary care through digital diagnostics, training and improved referral pathways in support of the county’s UHC efforts.Accenture

While these examples extend beyond pure teleconsultation, they illustrate how PPPs are already being used to embed digital technologies into Kenya’s service delivery architecture.

Teleconsultation platforms themselves often incorporate PPP characteristics even without explicit PPP branding:

-

Use of public infrastructure (e.g., regulatory approvals, integration with national ID or insurance systems)

-

Partnerships with public or faith-based facilities for referrals and follow-up

-

Collaboration with government-backed initiatives (e.g., community health worker programmes)

-

Donor or development partner funding aligned with national health strategies

5. Case Examples of Teleconsultation Platforms and PPP-Like Arrangements

5.1 Sema Doc: Teleconsultation bundled with financial services

Sema Doc is one of Kenya’s earlier telemedicine services. It operates on the Safaricom network with approval from the Ministry of Health and was described as one of the first commercially licensed telemedicine services in Sub-Saharan Africa.GSMA Users dial a USSD short code to subscribe, pay a monthly fee and access doctor consultations by phone.

A later description portrays Sema Doc as a collaboration between multiple private actors: Hello Doctor (for medical consultations), NCBA (for health savings and loans) and Cannon Assurance (for hospital cash benefits).Engineering For Change The model thus bundles teleconsultation with health financing and micro-insurance, leveraging mobile money channels for subscription and payments.

From a PPP lens, Sema Doc exemplifies:

-

Public–private–private collaboration: public authorities licensing and enabling the service, an MNO providing network access, and financial/insurance partners de-risking health shocks.

-

Innovative packaging: combining teleconsultation with savings and credit to address both access to advice and the ability to pay for care.

-

Scalability challenges: subsequent reports on telemedicine hotlines in Kenya highlight difficulties such as low awareness, high churn and pricing sensitivity.GSMA+2Sollay Kenyan Foundation+2

5.2 Baobab Circle’s Afya Pap: Remote chronic care and teleconsultation

Baobab Circle, headquartered in Nairobi, has developed Afya Pap, a multi-award-winning digital platform focused on personalised chronic disease management.Baobab Circle+2CB Insights+2 Afya Pap uses AI and behavioural science to provide:

-

Personalised health coaching (e.g., diet, exercise)

-

Remote monitoring of blood pressure and blood glucose

-

Health education content

-

Virtual access to qualified health providers for advice and e-prescriptions

The service targets people living with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in countries including Kenya and Uganda, with a basic package reportedly priced as low as approximately USD 1 per month for low-income users.Swiss Re Foundation

Baobab Circle’s partnerships with providers, insurers and NGOs are not fully documented in the public domain, but project descriptions suggest collaboration with health systems and organisations to integrate remote monitoring and teleconsultation into chronic care pathways and to support value-based care models.Swiss Re Foundation+2PharmAccess+2 This places Afya Pap squarely within the PPP-enabling environment, particularly where public or donor funds subsidise access for low-income populations.

5.3 MYDAWA: Telehealth integrated with e-pharmacy and diagnostics

MYDAWA is one of Kenya’s most prominent digital health platforms. Initially launched as an online pharmacy, it has evolved into an integrated digital health ecosystem offering online doctor consultations, lab testing, electronic prescriptions, chronic care management and home delivery of medicines.IndigiLife+3MYDAWA+3Sauce+3

MYDAWA’s telehealth service allows users to speak with licensed healthcare providers via phone, who can then order medicines, lab tests and other services through the platform.MYDAWA+1 The company has attracted significant private equity investment to fuel expansion across Kenya and into Uganda, positioning itself as an all-in-one health platform.TechMoran+2Sauce+2

Although MYDAWA’s public sector linkages are not always explicitly framed as PPPs, they include:

-

Compliance with Ministry of Health regulations for pharmacies and telehealth providers

-

Potential integration with national health insurance financing and corporate/insurer health plans

-

Alignment with national digital health strategies that encourage interoperable, patient-centred digital care

MYDAWA’s growth illustrates how private investment can scale teleconsultation services, while raising questions about integration with public UHC frameworks and equity of access.

5.4 Penda Online: Low-cost teleconsultation and integrated care

Penda Health, a Kenyan primary-care provider, offers “Penda Online,” a telemedicine service promising access to a doctor in under 10 minutes, 24/7, at a low flat fee (e.g., KSh 99), including free medicine delivery within Nairobi.Penda Health

This model connects teleconsultation with a network of physical clinics and pharmacies, enabling:

-

Remote triage and consultation

-

Electronic prescribing

-

Medication delivery

-

Referral to in-person care as needed

Penda’s teleconsultation service demonstrates how private providers can blend virtual and physical care, with potential for PPPs where county health systems contract or collaborate with such networks for specific services or populations.

5.5 Hillgan Innovations: AI-powered telemedicine

Hillgan Innovations has developed an AI-powered telemedicine platform in Kenya, combining intelligent video consultation, adaptive bandwidth (to function in low-connectivity areas), smart diagnostics and digital prescriptions.Hillgan Innovations The platform aims to address geographic disparities in access, citing the concentration of specialists in urban centres and transportation barriers for rural patients.Hillgan Innovations+2VoiceOut+2

By leveraging AI and bandwidth optimisation, Hillgan represents a new generation of HealthTech actors whose technologies could be integrated into public service delivery—provided that regulatory frameworks for AI in healthcare, data use and accountability are robust.

5.6 Empower Health and digital chronic care PPPs

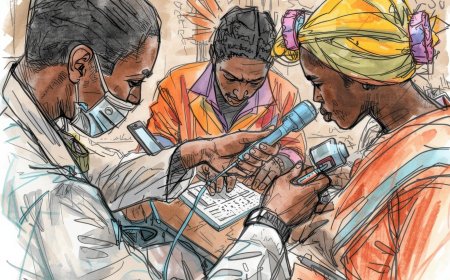

Empower Health, implemented by Medtronic LABS in partnership with Kenya’s Ministry of Health and several county governments, represents a nationally scaled PPP for technology-powered community healthcare delivery, especially for NCDs.Medtronic LABS+1 The model uses digital platforms, self-management devices and data analytics to support community health workers and clinics in managing hypertension and diabetes, including remote monitoring and patient engagement.

While Empower Health focuses more on longitudinal chronic care and less on direct patient-initiated teleconsultation, it showcases how PPPs can:

-

Embed digital tools into routine public service delivery

-

Enable data-driven, outcomes-focused care

-

Provide a blueprint for integrating teleconsultation and telemonitoring into UHC programmes

6. The Hits: Achievements of Teleconsultation PPPs in Kenya

6.1 Expanded access and convenience

Teleconsultation platforms have demonstrably expanded access to healthcare services, especially for patients in remote or underserved areas who face geographic, financial and social barriers to visiting facilities.Hillgan Innovations+4VoiceOut+4Katani Hospital+4 Key aspects of this “hit” include:

-

Overcoming distance and transportation costs: Patients can consult with clinicians without leaving their homes, saving travel costs and time away from income-generating activities.Katani Hospital+2Easy Clinic+2

-

Time-sensitive access: 24/7 models (e.g., Penda Online) allow patients to seek care outside regular clinic hours, which is particularly valuable for emergencies, parents with young children, or people in formal employment.Penda Health+1

-

Stigma reduction for sensitive conditions: Telemedicine offers a more private channel for mental health, sexual and reproductive health and other sensitive services, potentially reducing stigma-related barriers.Katani Hospital+2VoiceOut+2

These access gains are magnified when platforms integrate with medicine delivery (MYDAWA, Penda), chronic-care programmes (Afya Pap, Empower Health) or health financing mechanisms (Sema Doc’s savings and credit model).

6.2 Improved management of chronic diseases

Kenya, like many LMICs, faces a growing burden of NCDs, including hypertension and diabetes. Teleconsultation and remote-monitoring tools can support continuous, patient-centred management of these conditions.

Case studies from digital chronic-care models in Kenya demonstrate that combining self-management devices, digital platforms and clinical oversight can improve treatment adherence, monitoring and clinical outcomes.The Health Tech+3PharmAccess+3Medtronic LABS+3 Afya Pap’s remote coaching and virtual consultations, Empower Health’s community-based NCD model and telehealth components in MYDAWA’s chronic-care offerings all illustrate this potential.Sauce+3Swiss Re Foundation+3Medtronic LABS+3

From a PPP lens, chronic-disease teleconsultation can:

-

Reduce pressure on public outpatient clinics by shifting stable patients to remote follow-up

-

Enable task-sharing with community health workers supported by digital tools

-

Generate rich data for monitoring programme performance and informing policy

6.3 Efficiency and system-level benefits

Teleconsultation PPPs may improve system efficiency through:

-

Better triage: Teleconsultation can filter out cases that do not require facility visits, freeing up resources for more complex cases.kutrrh.go.ke+2Katani Hospital+2

-

Integration with logistics and diagnostics: Platforms like MYDAWA and Penda Online coordinate consultations, prescriptions, lab tests and delivery, streamlining patient journeys and reducing duplication.Sauce+3MYDAWA+3Penda Health+3

-

Data for planning: PPPs like Empower Health generate outcome and utilisation data that can inform policymaking, resource allocation and quality improvement.Medtronic LABS+1

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine globally and in Kenya helped maintain continuity of care while reducing infection risk, demonstrating the value of remote services for health system resilience.VoiceOut+1

6.4 Mobilisation of private capital and innovation

Teleconsultation PPPs have attracted private investment and innovation:

-

Private equity and impact investors have supported platforms like MYDAWA to scale, bringing capital and managerial expertise.TechMoran+2IndigiLife+2

-

HealthTech start-ups such as Baobab Circle and Hillgan Innovations are piloting AI, behavioural science and adaptive technologies that can enhance care quality and access.CB Insights+3Baobab Circle+3The Health Tech+3

-

International industry players such as Philips and Medtronic, through PPPs with Kenyan actors, have introduced digital diagnostic and chronic-care models that demonstrate scalable, data-driven care.Medtronic LABS+2Accenture+2

These innovations align with the Ministry of Health’s recognition that digital ecosystems will be central to future healthcare, and that private sector capacity is essential to build and sustain these systems.DLA Piper Africa+2Keli Kenya+2

7. The Misses: Gaps and Challenges in Teleconsultation PPPs

Despite clear gains, Kenya’s teleconsultation PPPs face multiple challenges.

7.1 Regulatory uncertainty and fragmentation

Although the Digital Health Act and E-Health Bill mark significant progress, the regulatory environment for teleconsultation remains in flux. Draft regulations for digital health and telemedicine are still being finalised, and questions persist around:

-

The precise scope and licensing pathways for telemedicine providers

-

Cross-border service provision (e.g., foreign-based clinicians consulting Kenyan patients)

-

Standards for clinical quality, record-keeping and prescriptions

-

Integration with professional councils’ regulations and disciplinary processes

The Ministry of Health’s regulatory impact statements acknowledge that telemedicine had previously operated in a largely unregulated space, and that coherent regulations are needed to safeguard patient rights and data while encouraging innovation.Ministry of Health Kenya+2Ministry of Health Kenya+2

From a PPP perspective, regulatory uncertainty can deter both public purchasers (e.g., SHIF) and private investors from fully committing to teleconsultation models, leading to short-term pilots rather than long-term, scaled partnerships.

7.2 Fragmented financing and limited integration into SHIF

Teleconsultation platforms in Kenya currently rely predominantly on:

-

Out-of-pocket payments (e.g., subscription or per-consultation fees)

-

Corporate or private insurance packages

-

Donor-funded or project-based subsidies

Systematic inclusion of teleconsultation in national health insurance benefits remains limited and is not yet clearly articulated in the SHIF transition discourse.Positive Voice of Kenya+4Nation Africa+4KHF+4

This has several implications:

-

Equity: low-income and informal-sector populations may be priced out of teleconsultation services unless subsidies or public purchasing mechanisms are implemented.

-

Sustainability: platforms must balance affordability with cost-recovery, often resulting in narrow offerings or urban-focused models.

-

Incentives: without clear reimbursement policies, providers may underinvest in teleconsultation capacity or use it mainly as a marketing funnel to in-person services.

Further, reimbursement designs (e.g., fee-for-service vs. capitation vs. value-based contracts) will shape whether teleconsultation is used appropriately or overused for revenue generation.

7.3 The digital divide and exclusion risks

While mobile penetration is high, access to reliable internet, smartphones and digital literacy remains uneven across Kenya. Telemedicine analyses highlight limited internet and smartphone access in rural areas as a major constraint to telehealth expansion.Easy Clinic+3Katani Hospital+3VoiceOut+3

Groups most at risk of exclusion include:

-

Rural and remote populations without stable connectivity

-

Women, especially in low-income households, where phone ownership and control may be gendered

-

Older adults with lower digital literacy

-

People with disabilities requiring accessible interfaces

Unless PPPs deliberately invest in inclusive design—supporting USSD/voice channels, community digital literacy, subsidised devices or connectivity—teleconsultation risks widening, rather than narrowing, health inequities.

7.4 Data protection, privacy and trust

Digital health inherently involves collecting, storing and processing sensitive health information. Kenyan civil society and legal analyses have emphasised that digital health policies must place patient empowerment, privacy and data governance at their core.Keli Kenya+2Ministry of Health Kenya+2

Concerns include:

-

Who owns and controls health data collected by private teleconsultation platforms?

-

How are data shared with public systems, insurers or third parties?

-

Are consent processes meaningful for patients, especially in low-literacy settings?

-

What safeguards exist against data breaches, misuse or discriminatory profiling?

These questions are not unique to Kenya but are particularly salient in PPP contexts, where public authorities may rely on private platforms for data infrastructure. Insufficient attention to data governance can erode public trust and undermine adoption of teleconsultation services.

7.5 Business model fragility and pilot fatigue

Telemedicine commentary and case profiles suggest that many teleconsultation initiatives struggle with commercial viability, user acquisition and retention. Health hotlines and mobile subscription services have faced limited awareness, pricing sensitivity and difficulties achieving sustainable scale.GSMA+2Sollay Kenyan Foundation+2

Business model challenges include:

-

High customer acquisition costs and low willingness or ability to pay

-

Regulatory and licensing costs that may be burdensome for start-ups

-

Limited integration with formal payment streams (e.g., SHIF, employers, insurers)

-

Dependence on donor funding with unclear paths to long-term sustainability

Moreover, PPPs in Kenya’s health sector have sometimes been criticised for limited transparency, inadequate value-for-money assessment and misaligned incentives.IA Journals+1 Without robust governance, teleconsultation PPPs risk becoming short-lived pilots or raising public concern about private enrichment at the expense of public funds.

8. Opportunities Galore: Future Directions for Teleconsultation PPPs

Despite the “misses,” Kenya’s current policy, technological and financing transitions create a rich opportunity space for teleconsultation PPPs.

8.1 Aligning SHIF benefit design with teleconsultation

As SHIF benefit packages and provider payment mechanisms are finalised, Kenya has a window to explicitly integrate teleconsultation services in ways that promote equity and efficiency.KHF+2CR Advocates LLP |+2 Potential approaches include:

-

Including teleconsultation as a covered service for primary care and selected specialist consultations, with appropriate clinical protocols

-

Bundling teleconsultation into capitation or blended payment models for primary care networks, incentivising continuity and prevention

-

Piloting value-based contracts, where teleconsultation platforms are rewarded for improving outcomes or reducing avoidable hospitalisations (e.g., for NCDs)

Such integration would transform teleconsultation from a primarily out-of-pocket, privately accessed service into a mainstream component of UHC.

8.2 Developing PPP frameworks specific to digital health

Kenya’s PPP frameworks have historically focused on infrastructure and large-scale service contracts. To fully harness teleconsultation, there is a need for PPP guidance tailored to digital health, addressing:

-

Procurement and contracting models for digital platforms

-

Risk-sharing arrangements around technology obsolescence, cybersecurity and data loss

-

Interoperability and open standards as contractual requirements

-

Local innovation and capacity-building provisions

Law firm analyses already note that digital technologies are expanding the space for private sector involvement in healthcare and that the Digital Health Bill is timely in this regard.DLA Piper Africa+2Keli Kenya+2 Turning these insights into operational PPP frameworks would help both public and private actors negotiate more balanced, transparent partnerships.

8.3 Strengthening data governance and patient rights

As draft regulations under the Digital Health Act are finalised, Kenya can embed strong protections for data privacy and patient rights while enabling responsible data use.Ministry of Health Kenya+2Ministry of Health Kenya+2 For teleconsultation PPPs, this could entail:

-

Clear rules on data ownership, storage, access and sharing between public and private parties

-

Mandatory adoption of privacy-by-design and security-by-design principles in digital platforms

-

Requirements for transparent, user-friendly consent mechanisms

-

Independent oversight bodies or mechanisms with enforcement powers

Such governance would build trust in teleconsultation services and reduce the risk of harmful data practices.

8.4 Building inclusive connectivity and digital literacy

Closing the digital divide is essential to ensure teleconsultation benefits are equitably distributed. PPPs can support inclusive digital infrastructure and skills through:

-

Partnerships between government, MNOs and donors to extend network coverage and subsidise connectivity for health services

-

Device-financing schemes (possibly linked to health savings/insurance products) for low-income users

-

Community-based digital literacy programmes (e.g., training community health workers and patient advocates to support teleconsultation uptake)

Telemedicine analyses of Kenya already highlight how government–private collaborations in expanding digital infrastructure have laid foundations for telehealth growth.VoiceOut+1 Scaling such collaborations, with equity explicitly foregrounded, would enhance the reach of teleconsultation PPPs.

8.5 Supporting AI and advanced analytics responsibly

AI-powered telemedicine, exemplified by Hillgan Innovations and data-driven models such as Empower Health and Afya Pap, offers opportunities to:

-

Enhance diagnostic accuracy and decision-support

-

Personalise care based on behavioural and clinical data

-

Optimise resource allocation through predictive analytics

However, PPPs must ensure that AI systems are transparent, contestable and subject to ethical and regulatory oversight, particularly where they influence clinical decisions or benefit determinations.Medtronic LABS+3Hillgan Innovations+3PharmAccess+3

Developing guidelines for AI in healthcare under the Digital Health Act framework—and incorporating them into PPP contracts—would help avoid algorithmic bias and ensure accountability.

8.6 Regional expansion and cross-border learning

Kenya’s teleconsultation platforms and PPP experiences are increasingly relevant beyond its borders. Platforms like MYDAWA and Afya Pap have expanded or plan to expand into other African markets, while PPPs such as Empower Health operate across multiple countries.Medtronic LABS+3TechMoran+3Sauce+3

This creates opportunities for:

-

Cross-country learning on teleconsultation regulation, reimbursement and PPP models

-

Harmonisation efforts (e.g., East African Community standards) that facilitate cross-border telehealth services

-

Export of Kenyan HealthTech innovations and partnership models, supporting economic as well as health development

9. Policy and Practice Recommendations

Drawing on the hits, misses and opportunities identified, this section outlines practical recommendations for key stakeholder groups.

9.1 For the Government of Kenya and the Ministry of Health

-

Explicitly integrate teleconsultation into SHIF benefits and provider payment mechanisms.

-

Identify essential teleconsultation services for primary care and selected specialties.

-

Develop reimbursement tariffs and clinical guidelines aligned with quality and cost-effectiveness.Positive Voice of Kenya+3KHF+3CR Advocates LLP |+3

-

-

Finalise and operationalise digital health and telemedicine regulations with clear licensing pathways.

-

Provide detailed guidance on registration and accreditation of telemedicine providers.

-

Clarify cross-border service provision and liability arrangements.Parliament of Kenya+3Ministry of Health Kenya+3Ministry of Health Kenya+3

-

-

Develop PPP frameworks specific to digital health.

-

Issue model contracts and guidelines for digital health PPPs, including risk allocation and performance metrics.

-

Embed requirements for interoperability, open standards and data governance in all digital health PPPs.Accenture+3DLA Piper Africa+3Keli Kenya+3

-

-

Strengthen multi-level governance and coordination.

-

Support county governments to design and manage digital health PPPs aligned with national standards.

-

Create inter-agency mechanisms linking MoH, ICT authorities, data protection offices and professional councils around teleconsultation governance.

-

9.2 For Teleconsultation Platforms and Private HealthTech Companies

-

Design for equity and inclusivity.

-

Maintain and improve USSD and voice channels for low-end phone users.

-

Partner with community-based organisations and CHWs for digital literacy and onboarding.Easy Clinic+3Katani Hospital+3VoiceOut+3

-

-

Work towards SHIF compatibility and integration.

-

Align platform data structures and workflows with national health information system standards.

-

Engage with the Social Health Authority to pilot teleconsultation reimbursement models.Medinous+2KHF+2

-

-

Adopt privacy- and security-by-design.

-

Implement robust data protection, encryption and access controls.

-

Provide transparent privacy policies and patient-friendly consent flows.Keli Kenya+2Ministry of Health Kenya+2

-

-

Generate and share evidence.

-

Conduct and publish real-world evaluations of teleconsultation’s impact on access, outcomes and costs, ideally with independent partners.Academia+3PharmAccess+3Medtronic LABS+3

-

9.3 For Development Partners and Investors

-

Support catalytic PPPs that are embedded in national systems.

-

Prioritise programmes that integrate teleconsultation into public primary care, chronic-disease and community health strategies rather than one-off pilots.Medtronic LABS+2Accenture+2

-

-

Encourage responsible innovation.

-

Fund AI and advanced analytics projects that include ethical, regulatory and equity components.Hillgan Innovations+2Swiss Re Foundation+2

-

-

Support digital public goods and open standards.

-

Invest in shared infrastructure (e.g., interoperability layers, open-source tools) that multiple teleconsultation platforms can use, reducing vendor lock-in.

-

10. Conclusion

Kenya’s HealthTech ecosystem, and teleconsultation in particular, stands at a pivotal moment. Over the last decade, a combination of entrepreneurial energy, supportive policy rhetoric and pragmatic public–private collaboration has produced a diverse array of teleconsultation platforms—from early USSD-based hotlines like Sema Doc to integrated chronic-care models like Afya Pap and large-scale digital health ecosystems like MYDAWA.TechMoran+6GSMA+6Engineering For Change+6

“The hits” are real: teleconsultation has expanded access and convenience, improved chronic-disease management, introduced new efficiencies and attracted private capital and technological innovation. Articles and case studies on telemedicine in Kenya consistently highlight its potential to bridge geographic and infrastructural gaps and to support confidential, patient-centred care.Hillgan Innovations+3VoiceOut+3Katani Hospital+3

Yet “the misses” cannot be ignored. Regulatory uncertainty, fragmented financing, digital divides, data governance concerns and fragile business models mean that teleconsultation risks remaining a patchwork of pilots and boutique services rather than a cornerstone of UHC. Evaluations of PPPs in Kenyan healthcare more broadly also warn that without careful design and oversight, such partnerships may not deliver the promised value for money or equity gains.Positive Voice of Kenya+3IA Journals+3Academia+3

The “opportunities galore” lie in the alignment of three trends: (1) the finalisation and operationalisation of the Digital Health Act and related regulations, (2) the design and rollout of SHIF and its benefits and payment structures, and (3) the maturation of Kenya’s teleconsultation market and broader digital infrastructure.VoiceOut+6Ministry of Health Kenya+6Ministry of Health Kenya+6

If Kenya seizes this moment—by embedding teleconsultation within SHIF, creating PPP frameworks tailored to digital health, investing in inclusive connectivity and digital literacy, and upholding strong data governance—teleconsultation PPPs could become powerful engines of equitable, resilient and people-centred health systems. Conversely, if these opportunities are missed, teleconsultation may entrench a two-tier system, where digital convenience is the privilege of those who can pay or connect, while public systems lag behind.

In short, Kenya’s experience with teleconsultation PPPs offers a compelling case study for other countries navigating the intersection of digital health, public–private collaboration and UHC. The next few years will determine whether this story is remembered primarily for its hits, its misses, or for the bold choices that transformed “opportunities galore” into tangible health gains for all.

References

(Formatted in APA style; URLs omitted here for brevity but should be included in a final manuscript.)

Baobab Circle. (n.d.). Baobab Circle Limited: Transforming healthcare from anywhere.

Baobab Circle. (n.d.). Managing chronic disease through digital tech: Afya Pap.

DLA Piper Africa. (2023). Digital technologies expand space for private sector in healthcare.

Engineering for Change. (n.d.). Sema Doc.

Health.go.ke. (2023). The E-Health Bill, No. 32 of 2023.

Health.go.ke. (2023–2024). Digital Health Act (No. 15 of 2023) and draft digital health (data exchange) regulations.

Health.go.ke. (2024). Regulatory Impact Statement for regulations to the Digital Health Act No. 15 of 2023.

Hillgan Innovations. (2025). AI-powered telemedicine: How Hillgan Innovations connects patients and doctors anywhere in Kenya.

Katanihospital.org. (2025). The role of telemedicine in expanding healthcare access in Kenya.

KELIN Kenya. (2023). Patient empowerment, innovation, interoperability and privacy: The core of the Digital Health Bill 2023.

Kenya Healthcare Federation. (2024). Frequently asked questions on the Social Health Authority (SHA).

Medinous. (2024). Navigating NHIF in Kenya: What it is, why it matters, and integration with hospital systems.

Medtronic LABS. (n.d.). Empower Health Kenya partnership.

MYDAWA. (n.d.). Telehealth: Talk to a doctor on phone for free, anywhere.

Penda Health. (n.d.). Talk to a Penda doctor online – 24/7.

PharmAccess Foundation. (2024). Research brief: Digital and mobile-based chronic care model in Kenya.

Positive Voice of Kenya. (2025). Telemedicine in Kenya: A promising solution or a temporary fix?

SD Onyango. (2019). Telemedicine in Kenya – 5 years on.

Sollay Kenyan Foundation. (2024). Innovations in telemedicine: Connecting remote areas to healthcare services in Kenya.

Swiss Re Foundation. (n.d.). Baobab Circle: Managing chronic disease through digital tech.

TechMoran & other tech media. (2025). MYDAWA raises funding to expand its AI-driven digital health platform across Kenya & Uganda.

The HealthTech Hub Africa. (n.d.). Baobab Circle company profile.

Voiceout.or.ke. (2024). Telemedicine: A digital bridge to healthcare in Kenya.

Accenture. (n.d.). Model of health for primary care in Kenya: Philips–Amref–Makueni PPP.

IAJournals.org. (n.d.). Influence of public–private partnership on healthcare service delivery in Kenya.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0