Teleconsultation in Kenya: Reducing Patient Waiting Times Through Digital Innovation and Entrepreneurial Opportunity

This secondary research paper examines how teleconsultation in Kenya can reduce long patient waiting times while unlocking innovative, creative, and entrepreneurial opportunities across the country’s digital health ecosystem. It reviews national policies, empirical evidence, barriers, business models, and practical recommendations for policymakers, health providers, and start-ups.

Abstract

Kenya’s health system faces persistent challenges of limited health workforce, uneven geographical distribution of services, and long patient waiting times, especially in public and high-volume urban facilities. These delays reduce patient satisfaction and can negatively affect health outcomes and trust in the system. Recent advances in digital health – particularly teleconsultation (remote clinical encounters via video, audio, or text) – offer a promising pathway to alleviate congestion in physical facilities, extend specialist reach, and redesign patient flows.

This secondary research paper synthesizes existing literature, policy documents, reports, and grey literature on teleconsultation and broader telemedicine in Kenya, with a specific focus on how these tools can reduce waiting times and what innovative, creative, and entrepreneurial opportunities emerge as a result. It draws on Kenya’s National eHealth Policy 2016–2030, recent digital health regulations, workforce analyses, telemedicine utilization studies, and global evidence showing telemedicine’s impact on waiting times and access to care.ScienceDirect+4health.eac.int+4Ministry of Health+4

The paper begins with a contextual overview of Kenya’s healthcare system, highlighting the burden of long queues and the structural drivers such as health worker shortages and urban–rural disparities. It then reviews the evolution of teleconsultation in Kenya, including provider-to-provider and provider-to-patient models, and examines evidence on how telemedicine affects waiting times locally and globally. A dedicated section explores innovative and entrepreneurial opportunities: platform-based telehealth ventures, AI-assisted triage, integration with community health workers, digital pharmacy collaborations, and business-to-business (B2B) models serving hospitals, insurers, and employers.

The analysis also discusses constraints – such as connectivity gaps, digital literacy, regulatory complexities, reimbursement questions, and data protection requirements – and offers policy recommendations to create an enabling ecosystem for teleconsultation as a mainstream component of universal health coverage. The paper concludes that while teleconsultation will not automatically eliminate waiting times, it can substantially reduce avoidable queues, redistribute workload, and catalyze a vibrant digital health entrepreneurship landscape if strategically supported by government, regulators, investors, and providers.

Keywords: Teleconsultation, telemedicine, Kenya, waiting times, digital health, universal health coverage, entrepreneurship, health innovation

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Kenya, a lower-middle-income country in East Africa, has made important progress in expanding health services but still struggles with gaps in access, quality, and equity. A persistent structural constraint is the shortage and uneven distribution of health workers. Recent analyses suggest that Kenya has roughly 19 doctors per 100,000 people – about 1 doctor for every 5,263 citizens – far below the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendation and the densities associated with strong primary health care systems.Africa Uncensored+1 Even when nurses, midwives, and clinical officers are added, the combined health worker density remains significantly below global targets, and there is marked variation across counties.BMJ Global Health+2nairobibusinessmonthly.com+2

As a result, patients commonly encounter long queues at outpatient departments, emergency rooms, and specialist clinics. A recent study conducted in the emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Nairobi found that patients’ perception of waiting time significantly influenced satisfaction and their evaluation of care quality.PLOS These delays are not only an inconvenience; they shape utilization patterns, can deter timely care-seeking, and can exacerbate health inequities when marginalized populations face higher opportunity costs to attend clinics.

At the same time, Kenya has become a regional leader in mobile connectivity and digital innovation. High mobile phone penetration, expanding broadband, and a vibrant technology start-up ecosystem – famously associated with mobile money platforms like M-Pesa – have laid the foundation for digital health solutions. The Ministry of Health’s National eHealth Policy 2016–2030 explicitly recognizes telemedicine as a key tool for extending services and improving efficiency.health.eac.int+2repository.kippra.or.ke+2 More recently, the government has introduced digital health regulations and strategies that emphasize electronic health records, interoperable systems, and telemedicine as part of the path to universal health coverage (UHC) and Vision 2030.Ministry of Health+2Ministry of Health+2

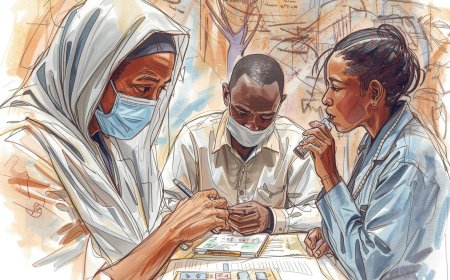

Against this backdrop, teleconsultation – synchronous or asynchronous remote consultations between patients and clinicians (or between providers) using information and communication technologies – has gained attention in Kenya. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated telemedicine adoption worldwide, and Kenyan studies report increased awareness and utilization of telemedicine among doctors, though much of it remains provider-to-provider rather than direct patient care.Wiley Online Library+2Europe PMC+2

1.2 Problem of Long Waiting Times in Kenya

Long patient waiting times in Kenyan health facilities arise from multiple drivers:

-

Health workforce shortages: Inadequate numbers of physicians and other cadres relative to population needs.Africa Uncensored+1

-

Maldistribution: Concentration of specialists in major urban centers like Nairobi and Mombasa, leaving rural and remote areas underserved.nairobibusinessmonthly.com+1

-

Infrastructure and logistics constraints: Limited consultation rooms, diagnostic capacity, and fragmented appointment systems.clincolhealth.com+1

-

Administrative inefficiencies: Paper-based or poorly integrated scheduling and triage processes that result in unpredictable queues and bottlenecks.

-

Demand–supply mismatch: Periodic health worker strikes and disruptions – as documented during COVID-19 – further reduce effective capacity and lengthen waiting times.ScienceDirect+1

Waiting time is thus both a symptom and a cause of system stress. Patients who experience very long waits may leave before being seen, delay follow-up visits, or avoid public facilities altogether, opting instead for private or informal providers where costs may be higher or quality variable.

1.3 Teleconsultation as a Response

Teleconsultation offers several potential mechanisms to address these challenges:

-

Decoupling location from consultation: Patients in remote or congested settings can see clinicians without physically traveling to a tertiary or county hospital.

-

Time-shifting and asynchronous care: Non-urgent cases can be managed via asynchronous messaging or store-and-forward consultations, smoothing demand across the day and reducing peak congestion.ScienceDirect+1

-

Optimized triage: Tele-triage can help determine whether a physical visit is necessary and, if so, prioritize cases, thereby shortening waits for those who truly need in-person care.

-

Task-sharing and extended reach: Specialists can support primary care providers through provider-to-provider teleconsultations, enabling local management of cases that would otherwise fill referral queues.Frontiers+1

Global evidence suggests that telemedicine, when properly implemented, can reduce waiting times for elective specialist consultations and follow-up visits, especially in disciplines like dermatology, psychiatry, and chronic disease management.bmjopen.bmj.com+2ScienceDirect+2

1.4 Purpose and Objectives of the Paper

This paper has two main aims:

-

To synthesize secondary evidence on teleconsultation in Kenya and its potential to reduce patient waiting times.

-

To identify innovative, creative, and entrepreneurial opportunities that emerge from integrating teleconsultation into Kenya’s health system.

Specific objectives are to:

-

Review the policy and regulatory context governing teleconsultation in Kenya.

-

Map current models and use cases of teleconsultation in Kenyan health care.

-

Examine empirical and theoretical evidence linking teleconsultation to reduced waiting times.

-

Explore business models and innovation spaces for Kenyan entrepreneurs and health-tech start-ups.

-

Discuss barriers, risks, and policy recommendations to unlock teleconsultation’s full potential.

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

2.1 Defining Teleconsultation and Telemedicine

Telemedicine is commonly defined as the delivery of healthcare services at a distance using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment, prevention of disease and injuries, research, and continuing education.MDPI+1

Teleconsultation is a specific subset of telemedicine, referring to remote clinical consultations, which may occur:

-

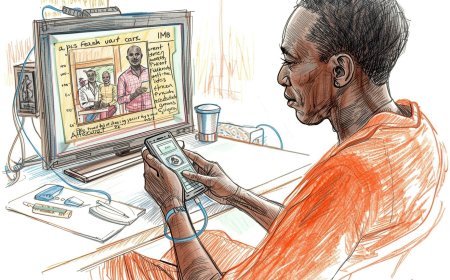

Provider-to-patient (P2P): A clinician consults directly with a patient via video, audio call, or secure messaging.

-

Provider-to-provider (P2P2): A clinician seeks advice from a specialist or another clinician regarding a patient’s case, often asynchronously.

In Kenya, available studies indicate that telemedicine is used more extensively for provider-to-provider consultations and education, with relatively limited direct use in routine patient care so far.Wiley Online Library+2Europe PMC+2

Teleconsultation occurs through several modalities:

-

Synchronous (real-time): Live audio or video sessions; closest analogue to traditional face-to-face consultations.

-

Asynchronous (store-and-forward): Transmission of clinical information, images, and history for later review.

-

Remote monitoring: Ongoing collection of patient data (e.g., blood pressure, glucose, asthma peak flow) with remote review and feedback.MDPI+1

2.2 Theoretical Lenses

This paper uses three complementary theoretical lenses:

-

Access-to-care frameworks (e.g., availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability, and accommodation) to understand how teleconsultation affects different dimensions of access, particularly the “accommodation” dimension, which includes scheduling and waiting times.

-

Technology Acceptance and Diffusion of Innovations theories to frame adoption among clinicians and patients, highlighting perceived usefulness, ease of use, compatibility with workflows, and social norms as determinants of teleconsultation uptake.MDPI+1

-

Queueing theory and operations management perspectives to analyze how teleconsultation changes patient flow, reduces congestion, and reallocates demand from physical to virtual “queues.” These perspectives emphasize managing arrival rates, service times, and variability to reduce waiting times without necessarily increasing total capacity.ScienceDirect+1

3. Methodology of the Secondary Research

This paper is based on secondary research – a desk-based narrative review rather than primary data collection. The process involved:

-

Searching academic databases (e.g., PubMed, Scopus), global organization repositories (WHO, World Bank), and Kenyan government portals for literature on telemedicine, teleconsultation, waiting times, and digital health in Kenya.

-

Reviewing Kenyan policy documents, including the National eHealth Policy 2016–2030, UHC policies, and recent digital health regulations and position papers.khf.co.ke+4health.eac.int+4PolicyVault.Africa+4

-

Identifying empirical studies on telemedicine utilization and barriers among Kenyan doctors and health facilities.Wiley Online Library+2Europe PMC+2

-

Including global systematic reviews on telemedicine and waiting times, where Kenyan-specific evidence was limited, to infer implications for the Kenyan context.bmjopen.bmj.com+1

-

Incorporating grey literature, think-tank reports, and media analyses on waiting times, health workforce shortages, and digital health innovations in Kenya.WHO | Regional Office for Africa+3Africa Uncensored+3BusinessWorld Africa+3

The goal is not to provide an exhaustive systematic review but to assemble a coherent synthesis that informs policy and entrepreneurial strategy.

4. Healthcare Access, Waiting Times, and System Pressures in Kenya

4.1 Health Workforce and Infrastructure

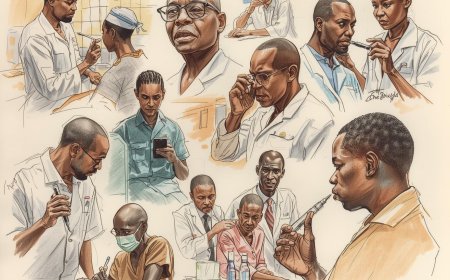

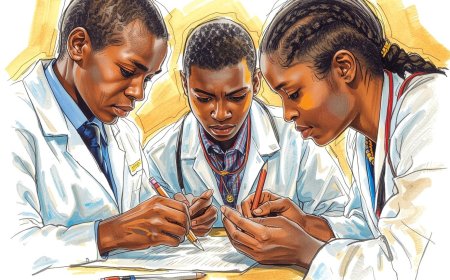

Kenya’s health workforce has roughly doubled in the past decade to nearly 190,000 active health workers across multiple occupations. However, this growth has not fully kept pace with population needs, and workforce density remains below the levels required for UHC.WHO | Regional Office for Africa+2BMJ Global Health+2

Estimates indicate:

-

Around 19 doctors per 100,000 people, translating to approximately 1:5,263 doctor–patient ratio, compared to WHO’s recommendation of about 1:1,000.Africa Uncensored+1

-

National density of core health personnel (doctors, nurses, midwives, clinical officers) around 15–30 per 10,000 population, below the threshold of 44.5 per 10,000 associated with progress toward SDG 3.Ministry of Health+2BMJ Global Health+2

-

Defined gaps in both numbers and distribution, with some counties exceeding recommended thresholds while many rural and marginalized areas fall far below.nairobibusinessmonthly.com+1

Infrastructure challenges compound these workforce issues. Many facilities lack sufficient consultation rooms, diagnostic equipment, and robust appointment systems, leading to crowded waiting areas and inefficient patient flow.clincolhealth.com+1

4.2 Evidence on Waiting Times and Patient Experience

Research on waiting times in Kenya is still emerging but growing. A 2023 prospective study in the emergency room of a major private-not-for-profit hospital in Nairobi found that:

-

Patients spent considerable time waiting before being seen, and

-

Their perception of waiting time (not only the actual duration) strongly predicted satisfaction and perceived quality of care.PLOS

While this study focused on an emergency department, its findings align with broader literature: long waits undermine trust, deter utilization, and may push patients toward private or informal providers even when they cannot easily afford them.

In public facilities, anecdotal and journalistic reports describe situations in which patients queue before dawn, wait many hours to see a clinician, or are asked to return another day due to overload. These experiences are especially pronounced in high-volume county referral hospitals and specialized clinics, such as oncology, dialysis, and obstetrics.

4.3 COVID-19 and Care Disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted routine health services in Kenya, with documented declines in outpatient visits, immunization, and some diagnostic services.ScienceDirect+1 While some of the reduction in waiting times during lockdowns may have been due to fewer patients seeking care, this came at the cost of delayed diagnosis and treatment.

During this period, telemedicine emerged as an alternative channel for continuity of care and for provider-to-provider specialist support. Kenyan hospitals and NGOs experimented with virtual consultations, remote triage, and helplines – experiences that have shaped the current discourse on digital health and teleconsultation.

5. Teleconsultation Landscape in Kenya

5.1 Policy and Regulatory Environment

The Kenya National eHealth Policy 2016–2030 provides the foundational policy framework for digital health, including telemedicine. It articulates a vision to create an environment conducive to sustainable adoption of eHealth products and services, including telemedicine, mHealth, and health information systems.health.eac.int+2PolicyVault.Africa+2 The policy acknowledges the need for appropriate legislation, standards, and interoperability frameworks.

Subsequently, the Ministry of Health has developed:

-

Standards and guidelines for mHealth systems and health information systems interoperability;

-

Kenya Health Enterprise Architecture; and

-

Draft regulations addressing electronic health and telemedicine, including data protection and professional liability issues.KMPDC+1

In 2024, Kenya announced new digital health regulations and a strengthened digital health strategy as part of the “digital superhighway” pillar in national development agendas. These regulations aim to standardize digital health, including telemedicine, promote interoperability, and protect patient data, aligning with Vision 2030 and the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA).Ministry of Health+2PATH+2

Furthermore, Kenya’s Data Protection Act (2019) and related guidelines define sensitive health data and obligations for data controllers and processors, with implications for teleconsultation platforms handling personal health information.Transform Health+1

5.2 Current Use and Adoption of Telemedicine

A semiquantitative cross-sectional survey among doctors in Kenya reported high awareness of telemedicine but relatively limited use in direct patient care. Most telemedicine activity occurred in doctor-to-doctor consultations, education, and case discussions, with barriers including inadequate ICT infrastructure, limited skills, high setup costs, weak policy frameworks, and lack of dedicated time.Wiley Online Library+2Europe PMC+2

The Addis Clinic’s provider-to-provider telemedicine platform, implemented in Kenya, has demonstrated sustained use during and after the second year of COVID-19, enabling primary providers in remote areas to seek specialist input asynchronously.Frontiers This model illustrates how teleconsultation can support providers at the periphery, potentially reducing referrals, travel, and waiting times at tertiary facilities.

Beyond provider-to-provider models, a range of private telehealth companies, hospital-based virtual clinics, and nonprofit initiatives offer direct-to-patient teleconsultations. These include:

-

Hospital-based teleconsultation services for follow-up visits and chronic disease management;katanihospital.org+1

-

Mobile health platforms enabling appointment booking, remote consultations, and digital payments;BusinessWorld Africa

-

Community health worker (CHW) programs that pair in-person visits with remote clinician support.MedRxiv+1

5.3 Digital Health Ecosystem and Innovation Actors

Kenya’s broader digital health ecosystem includes government bodies (Ministry of Health’s Digital Health Directorate), private health-tech companies, telecom operators, donors, NGOs, and innovation hubs. Business media and policy briefs highlight the role of companies like Ilara Health, Savannah Informatics, CarePay and others in driving digital health innovations such as EMRs, claims platforms, and data analytics.BusinessWorld Africa+2khf.co.ke+2

Teleconsultation is increasingly integrated into these broader platforms: EMR systems embed telehealth modules; insurance platforms incorporate virtual care benefits; and digital health entrepreneurs position teleconsultation as an entry point to more comprehensive digital health offerings.

6. Teleconsultation and Reduced Waiting Times: Evidence and Mechanisms

6.1 Global Evidence on Waiting Times

Globally, systematic reviews and empirical studies have reported that telemedicine can reduce waiting times in several ways:

-

Specialist access: Teleconsultation in specialties such as dermatology, mental health, and chronic disease management has shortened waiting times for first consultations and for follow-up visits, particularly in systems with long elective queues.bmjopen.bmj.com+1

-

Emergency and acute care support: Telemedicine programs that provide remote triage and specialist support to emergency departments have been associated with more efficient patient flow and shorter time-to-treatment for some conditions.bmjopen.bmj.com+1

-

Reduced no-shows and delayed follow-up: Remote visits can reduce travel and time costs, which in turn lowers missed appointments and allows better scheduling, indirectly shortening waits for other patients.

One study on telemedicine for chronic heart disease developed a scalable telemedicine model that reduced waiting times for remote patients by optimizing prioritization and monitoring, demonstrating how digital queues and remote monitoring can improve service flow.ScienceDirect

While these studies are predominantly from high-income settings, they offer insights into how teleconsultation alters patient flows and queue dynamics.

6.2 Emerging Evidence from Kenya and Sub-Saharan Africa

Kenya-specific quantitative evidence on teleconsultation’s impact on waiting times is relatively limited but growing. Rather than direct time-to-appointment measures, available studies focus on broader access and utilization outcomes:

-

A community-based telemedicine project integrating CHWs with virtual clinician support for maternal and newborn health showed improved uptake of postnatal care and engagement in underserved areas, suggesting a potential reduction in delays and missed visits.MedRxiv

-

A systematic review of telemedicine adoption and prospects in South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria concluded that telemedicine can address access barriers such as distance and long waiting times, but is constrained by infrastructure and policy challenges.MDPI

-

Provider-to-provider telemedicine services in Kenya, such as the Addis Clinic model, enable frontline providers to manage cases locally, potentially reducing the need for referral appointments at overburdened tertiary facilities.Frontiers+1

Even in the absence of direct Kenyan waiting-time metrics, combining global and regional evidence with Kenya’s policy objectives suggests that teleconsultation can:

-

Reduce physical crowding and queues for low-complexity and follow-up cases;

-

Shorten time-to-advice for health workers in remote facilities;

-

Prevent unnecessary referrals that would otherwise congest referral hospitals;

-

Provide alternative channels during system shocks (e.g., pandemics, strikes).

6.3 Mechanisms of Waiting Time Reduction

Teleconsultation can reduce waiting times through several operational mechanisms:

-

Digital Triage and Routing

-

Patients or CHWs complete structured symptom checkers or pre-consultation questionnaires.

-

Algorithms or clinicians score cases and route them to appropriate channels: self-care advice, teleconsultation, community visit, or in-person clinic.

-

Only those needing physical examination or procedures join the physical queue, shortening wait times for those who must be seen in person.

-

-

Asynchronous Consultation and Time-Shifting

-

Non-urgent queries (e.g., medication refills, lab result discussions, stable chronic disease reviews) can be handled via messaging or scheduled phone calls outside peak clinic hours.

-

Clinicians can batch these tasks, smoothing their workload and reducing congestion in walk-in clinics.

-

-

Decentralization of Care

-

Teleconsultation enables specialists to support primary care providers and CHWs in peripheral facilities. Local management of cases reduces referrals to central hospitals, shifting demand away from the longest queues.Frontiers+1

-

-

Reduced No-Shows and Improved Scheduling

-

Virtual visits lower travel time and cost, making it easier for patients to attend on time, reducing idle slots and allowing better prediction of demand.

-

-

Virtual “Fast-Track” Pathways

-

For certain conditions (e.g., mild dermatological issues, mental health counseling), entire episodes of care may occur virtually, bypassing physical queues altogether.katanihospital.org+1

-

When applied strategically, these mechanisms can significantly reduce average and maximum waiting times, even if the overall demand for care increases as access barriers are lowered.

7. Innovative, Creative, and Entrepreneurial Opportunities

A key focus of this paper is the innovation and entrepreneurship potential of teleconsultation in Kenya, particularly around reducing waiting times and improving patient flow. Kenya’s vibrant tech ecosystem, youthful population, and expanding digital infrastructure create fertile ground for health-tech ventures.

7.1 Platform-Based Teleconsultation Start-ups

Entrepreneurs can build or expand telehealth platforms that:

-

Provide on-demand or scheduled teleconsultations with general practitioners and specialists;

-

Integrate with mobile money and insurance systems for seamless payment;

-

Include appointment scheduling and digital queuing tools, allowing patients to “take a number” virtually and join either a physical or virtual queue;

-

Offer multilingual interfaces (English, Kiswahili, local languages) to increase accessibility.

Such platforms can partner with hospitals, clinics, and insurers to reduce waiting times by offloading low-acuity visits and providing alternative channels for follow-up care.

Business models include:

-

Direct-to-consumer (B2C): subscription or pay-per-consultation services marketed to middle-income urban users;

-

Business-to-business (B2B): white-label teleconsultation solutions for hospitals, employer health plans, or micro-insurance schemes;

-

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) with county governments or the national health insurance fund to provide virtual care to insured or vulnerable populations.BusinessWorld Africa+2khf.co.ke+2

7.2 AI-Enabled Triage and Queue Management

Innovative start-ups can develop AI-driven triage tools and queue management systems tailored to Kenyan conditions:

-

Symptom checker chatbots or voice-based systems that guide patients to appropriate care levels, reducing unnecessary facility visits.

-

Risk-stratification algorithms embedded in hospital information systems to prioritize high-risk patients and allocate teleconsultation vs in-person slots.

-

Predictive models to forecast clinic demand and waiting times based on historical attendance, weather, public events, and disease trends, allowing managers to adjust staffing and teleconsultation capacity proactively.ScienceDirect+2bmjopen.bmj.com+2

These tools can be sold as software-as-a-service (SaaS) to hospitals, integrated with existing EMRs, or bundled with teleconsultation platforms.

7.3 Hybrid Models with Community Health Workers

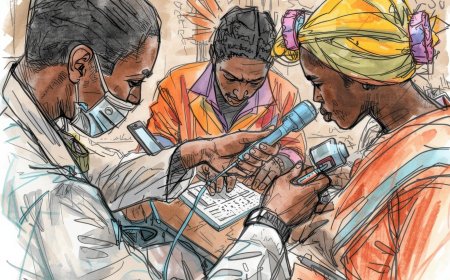

Kenya has a strong history of community health workers (CHWs) embedded in community health strategy. Teleconsultation creates opportunities for hybrid models:

-

CHWs equipped with smartphones or tablets conduct home visits, collect clinical data, and connect patients to remote clinicians in real time or asynchronously.

-

Teleconsultation hubs staffed by clinical officers or nurses can support CHWs across large geographic areas, reducing the need for patients to travel for routine follow-up and health education.MedRxiv+1

Entrepreneurial ventures can:

-

Provide devices, software, and connectivity bundles for CHWs;

-

Offer training and technical support;

-

Develop business models with county governments or NGOs where revenue comes from service contracts, performance-based payments, or donor funding.

By resolving many issues at the community level, these models can meaningfully reduce waiting times at higher-level facilities.

7.4 Teleconsultation in Pharmacies and Retail Health

Retail pharmacies are often more accessible than clinics, especially in urban informal settlements and small towns. Teleconsultation platforms can integrate with pharmacies to:

-

Offer remote consultations via kiosks, video booths, or shared tablets in pharmacies, enabling pharmacist-initiated teleconsultations with clinicians;

-

Provide rapid virtual review of prescriptions, drug interactions, or minor ailments, reducing crowding in primary care facilities.

Entrepreneurs can create networks of “tele-pharmacies” where waiting times are shorter, availability is extended into evenings and weekends, and services complement, rather than replace, formal clinics.

7.5 Niche Teleconsultation Vertical Start-ups

Specific clinical domains with high waiting times and specialist shortages present attractive niches:

-

Mental health: Virtual counseling, psychotherapy, and psychiatric follow-up where face-to-face capacity is scarce and stigma is high.

-

Maternal and newborn health: Teleconsultation support for antenatal and postnatal care, integrated with CHW home visits.MedRxiv+1

-

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs): Teleconsultations for hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease follow-up can substitute frequent facility visits.

-

Oncology and specialty care: Virtual follow-ups and second opinions to reduce travel and waiting times at specialized centers.kutrrh.go.ke

Each vertical can support specialized digital content, tailored triage tools, and custom workflows, providing competitive differentiation for start-ups.

7.6 Data and Analytics Ventures

As teleconsultation platforms scale, they generate rich data on demand patterns, waiting times, and clinical outcomes. Creative entrepreneurs can:

-

Develop analytics dashboards for hospitals and counties to monitor queues, teleconsultation uptake, and bottlenecks;

-

Offer decision-support tools that suggest where additional teleconsultation slots or CHW support could most reduce waiting times;

-

Support payers and policymakers in designing incentives for teleconsultation that align with UHC and cost-containment goals.BusinessWorld Africa+1

Of course, such data ventures must strictly comply with data protection laws and ethical standards.

8. Barriers, Risks, and Ethical Considerations

8.1 Infrastructure and Digital Divide

A major constraint is unequal internet and smartphone access, particularly in rural and low-income areas. While national smartphone penetration is rising, many Kenyans still have limited or unreliable connectivity.katanihospital.org+1

This digital divide risks creating two-tier access: urban, digitally connected populations enjoy reduced waiting times via teleconsultation, while rural and poorer groups remain stuck in long physical queues. Hybrid models that leverage CHWs, offline-first designs, and USSD or SMS-based triage can mitigate – but not entirely resolve – this challenge.

8.2 Capacity and Skills

Teleconsultation requires new skills for clinicians, managers, and patients:

-

Clinicians must adapt clinical reasoning and communication to remote modalities, including limitations in physical examination.

-

Facilities must reorganize workflows to integrate virtual and in-person queues.

-

Patients need guidance on using apps, video calls, and digital consent processes.

Studies among Kenyan doctors highlight limited ICT skills among both providers and patients as an important barrier to telemedicine uptake.Wiley Online Library+1

8.3 Regulatory and Reimbursement Uncertainty

Although Kenya has made progress in digital health policy, operational details around teleconsultation remain evolving:

-

Licensing and jurisdiction issues when clinicians serve patients across counties;

-

Standards of care and malpractice liability in remote consultations;

-

Rules on e-prescriptions and remote ordering of controlled medicines;

-

Reimbursement policies under national health insurance and private insurers for teleconsultation services.KMPDC+2PolicyVault.Africa+2

Ambiguity in these areas can discourage providers and investors. Clear regulations and pilot reimbursement models are essential to mainstream teleconsultation.

8.4 Data Protection and Privacy

Sensitive health data handled by teleconsultation platforms must comply with the Data Protection Act and related regulations, including robust security measures, informed consent, data minimization, and clear rights for data subjects.Transform Health+1

Risks include:

-

Unauthorized access or data breaches;

-

Misuse of health data for discriminatory purposes (e.g., insurance exclusion, employment decisions);

-

Loss of patient trust if privacy is compromised.

Entrepreneurs must embed privacy-by-design principles and invest in cybersecurity, encryption, and regular audits.

8.5 Quality and Equity Concerns

There is a risk that teleconsultation:

-

Exacerbates inequities if primarily targeted at affluent, digitally savvy populations;

-

Offers variable quality if unregulated platforms or unqualified providers deliver remote consultations;

-

Results in fragmented care if teleconsultation is not integrated with primary care records and referral systems.

Strong governance, accreditation of telemedicine services, and integration with national health information infrastructure are crucial to ensure that teleconsultation improves, rather than undermines, quality and equity.

9. Policy and Ecosystem Recommendations

To harness teleconsultation for reduced waiting times and innovation, coordinated action is needed across government, regulators, providers, and private sector actors.

9.1 Government and Regulators

-

Finalize and operationalize telemedicine regulations

-

Clearly define teleconsultation standards, scope of practice, informed consent requirements, and liability frameworks.

-

Align with the National eHealth Policy, UHC policies, and digital health strategy, while ensuring harmonization with the Data Protection Act.Transform Health+3health.eac.int+3PolicyVault.Africa+3

-

-

Establish reimbursement and financing mechanisms

-

Recognize teleconsultation as a reimbursable service under national health insurance schemes and public funding streams, at least for defined use cases (e.g., chronic disease follow-ups, mental health counseling).

-

Pilot bundled payments or capitation models that give providers flexibility to mix in-person and virtual care in ways that reduce waiting times and improve outcomes.

-

-

Invest in digital infrastructure and interoperability

-

Expand broadband coverage, especially in rural and underserved counties;

-

Promote use of interoperable EMRs and health information exchanges, guided by national standards and architectures;repository.kippra.or.ke+2KMPDC+2

-

Support shared teleconsultation platforms for public facilities to avoid fragmentation and duplication.

-

-

Incorporate teleconsultation into UHC and community health strategy

-

Embed teleconsultation explicitly in implementation guidelines for UHC, including packages of essential virtual services;

-

Provide frameworks and funding for CHW-linked telemedicine models, particularly in rural and informal urban settlements.MedRxiv+2Ministry of Health+2

-

9.2 Health Facilities and Providers

-

Redesign patient flow and triage systems

-

Introduce pre-visit tele-triage to route patients to virtual or in-person queues, with clear criteria for escalation;

-

Use appointment systems and digital tokens to reduce idle time and overcrowding in waiting rooms.

-

-

Integrate teleconsultation into routine care pathways

-

Identify clinical areas where remote care is safe and effective (e.g., chronic disease follow-up, stable HIV management, post-surgical check-ins) and embed teleconsultation into standard operating procedures.

-

-

Train health workers in digital competencies

-

Provide training in remote clinical assessment, communication etiquette, documentation, and privacy.

-

Encourage clinician champions to co-design teleconsultation workflows.Wiley Online Library+1

-

-

Measure and monitor waiting times

-

Collect data on both physical and virtual waiting times before and after teleconsultation implementation;

-

Use this data to iteratively refine triage, scheduling, and demand management strategies.PLOS+1

-

9.3 Entrepreneurs and Innovators

-

Design for low-resource settings

-

Build platforms that work on low-end Android phones, tolerate intermittent connectivity, and support offline workflows for CHWs;

-

Provide USSD/SMS options alongside apps to reach feature-phone users.

-

-

Align with national priorities and regulations

-

Engage early with the Ministry of Health, regulator bodies, and county governments to ensure compliance and co-creation;

-

Develop offerings that support government priorities like UHC, maternal and child health, and NCD control.Ministry of Health+2Ministry of Health+2

-

-

Focus on measurable value, including waiting time reduction

-

Demonstrate how platforms reduce waiting times, improve patient satisfaction, or increase provider productivity, using robust metrics;

-

Offer outcome-based pricing or shared-savings contracts where appropriate.

-

-

Build trust through privacy and quality

-

Adopt privacy-by-design principles, secure architectures, and transparent data use policies;

-

Collaborate with reputable providers and professional associations to maintain clinical quality.Transform Health+2KMPDC+2

-

-

Explore blended financing and partnerships

-

Combine revenue from B2B contracts, donor projects, and pay-per-use models to achieve financial sustainability;

-

Leverage innovation hubs, accelerators, and impact investors interested in health and technology.

-

10. Conclusion

Teleconsultation is not a magic bullet, but it is a powerful tool in Kenya’s quest to reduce long patient waiting times, expand access to care, and build a more resilient health system. Kenya’s combination of health workforce shortages, infrastructure constraints, and high patient demand generates predictable congestion in health facilities, especially in public and referral centers. At the same time, the country’s strengths in digital innovation, mobile connectivity, and entrepreneurship create a promising environment for teleconsultation to flourish.

Secondary evidence from global telemedicine research shows that remote consultations can reduce waiting times, particularly for specialist and follow-up care, by decoupling care from location, enabling time-shifting, and optimizing triage. Kenyan studies and programs – from provider-to-provider telemedicine platforms to CHW-linked telehealth pilots – demonstrate feasibility and growing adoption, even if direct empirical measures of waiting time reduction remain limited.MDPI+4bmjopen.bmj.com+4ScienceDirect+4

Teleconsultation also represents a rich frontier for innovation and entrepreneurship. Start-ups and established firms can build telehealth platforms, AI-enabled triage tools, analytics solutions, hybrid CHW–telemedicine models, pharmacy-based teleconsultation stations, and disease-specific vertical services. If designed inclusively and responsibly, these ventures can both create economic opportunity and contribute to public goals such as universal health coverage and equitable access.

However, realizing this potential requires deliberate action. Policymakers must complete and enforce supportive regulations, invest in digital infrastructure, and integrate teleconsultation into UHC and community health strategies. Providers must re-engineer workflows, train staff, and measure waiting times to ensure teleconsultation truly reduces congestion rather than simply adding new layers of complexity. Entrepreneurs must design for low-resource contexts, embed privacy and quality, and align their business models with health system priorities.

In short, teleconsultation in Kenya sits at the intersection of health system reform and digital innovation. Used well, it can transform queues from long, frustrating lines outside overcrowded clinics into flexible, patient-centered, and efficient pathways that blend physical and virtual care. For Kenya’s patients, this could mean shorter waits, earlier care, and more dignified service experiences. For innovators and policymakers, it offers an opportunity to co-create a health system that is not only more efficient, but also more responsive, equitable, and future-ready.

References

Note: The following references are derived from the sources cited in this paper. Some web-based documents do not provide full traditional bibliographic details; they are formatted here as accurately as the available information allows.

Addis Clinic. (2022). Use of provider-to-provider telemedicine in Kenya during the COVID-19 pandemic [Article]. Frontiers in Public Health.

BusinessWorld Africa. (2025). Kenya’s healthcare transformation by 2030: Community health strategy and digital innovations.

Giannoni, A., et al. (2025). Reducing outpatient wait times through telemedicine: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 15(1), e088153.

Government of Kenya, Ministry of Health. (2016). Kenya National eHealth Policy 2016–2030.

Government of Kenya, Ministry of Health. (2018). Optimizing human resources for quality health services in Kenya.

Government of Kenya, Ministry of Health. (2023). Health Labour Market Analysis for Kenya.

Government of Kenya, Ministry of Health. (2023). Kenya’s path to universal health coverage enhanced by digital health innovations.

Government of Kenya, Ministry of Health. (2024). Kenya takes major step towards digital health transformation with new regulations.

Katanihospital.org. (2024). The role of telemedicine in expanding healthcare access in Kenya.

Kenya Healthcare Federation. (2024). Position paper on the digital superhighway and the standardization of digital health.

Kiptoo, M., et al. (2023). Perception of waiting times on patient satisfaction at a tertiary hospital emergency department in Kenya. PLOS ONE, 18(8).

Mwakala, M. (2024). Mapping out a digital health strategy in Kenya. PATH.

Ndetei, D., et al. (2024). Telemedicine adoption and prospects in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria. Healthcare, 13(7), 762.

PesaCheck / Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Kenya’s doctor-to-patient ratio fact-check.

ReliefWeb / WHO. (2023). Strengthening the availability of evidence and fostering dialogue to stimulate investment in Kenya’s health workforce.

Transform Health. (2023). Legislative guide on digital health technologies and data in Kenya.

Wiley / Hindawi. (2023). Experiences on the utility and barriers of telemedicine in healthcare delivery in Kenya. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications.

World Bank. (2022). Physicians (per 1,000 people) – Kenya.

World Health Organization. (2024–2025). Medical doctors per 10,000 population – global health workforce statistics.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0