Financing Health Innovation: Grants, Seed Funds & Donor Models for Health Systems Innovation in Africa and the Global South

Financing health innovation is now a make-or-break issue for African and wider Global South health systems. As external aid plateaus and domestic budgets remain under pressure, governments, donors, investors, and innovators are searching for new ways to fund the tools, technologies, and service models that can deliver universal health coverage (UHC). This long-form feature unpacks how grants, seed funds, and donor financing models are evolving, and how they can be designed to support real health systems innovation rather than isolated pilot projects. Drawing on recent evidence from WHO, multilateral initiatives such as Gavi and the Global Fund, African health-tech investment trends, and case studies from countries like Ethiopia, Rwanda, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, India, and Brazil, the article offers a practical roadmap for financing innovation across the idea-to-scale continuum. It is tailored primarily to African and Global South audiences while remaining relevant to international funders and partners, and uses APA-style, evidence-based references throughout.

Introduction: Why Financing Health Innovation Matters Now

Health financing has always been a core function of health systems, but in Africa and much of the Global South, it is increasingly the pressure point that determines whether innovation remains a buzzword or actually changes people’s lives. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that millions of people still forgo needed care because of cost, while many others receive poor-quality services even when they do pay out of pocket. Carefully designed health financing policies are therefore essential for progress toward universal health coverage (UHC). World Health Organization

At the same time, the nature of health challenges is changing. The unfinished agenda of infectious diseases and maternal and child health now overlaps with rapidly rising non-communicable diseases (NCDs), mental health conditions, trauma, and climate-related shocks. For example, 5 billion people worldwide lack access to safe, timely, and affordable surgical and anaesthesia care, with unmet needs concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). BMJ Global Health Health systems in Africa and the Global South must innovate not just with new drugs, vaccines, or digital tools, but also with new models of service delivery, workforce, supply chain, regulation, and governance.

Yet innovation costs money at every step—from early-stage research and development (R&D), to piloting and testing, to scale-up and integration into routine systems. Traditional aid and government budgets are under strain. Development assistance for health (DAH) peaked around 2013 and has plateaued or declined in some areas, pushing low-income countries to rely more on domestic and “innovative” financing sources. The Lancet In Africa, overall startup funding—across all sectors—was about US$2.2 billion in 2024, just 0.6% of global startup funding, with health-tech capturing only a fraction. Where Founders are Stars

The question is no longer whether we need health innovation in the Global South, but how to pay for it in a way that strengthens health systems rather than fragmenting them.

This article looks at three major pieces of the puzzle:

-

Grants – from bilateral donors, philanthropies, and global health initiatives that seed ideas, de-risk experimentation, and underwrite public goods.

-

Seed funds and early-stage investment – including impact investors, accelerators, and blended finance vehicles that help ventures grow beyond the pilot stage.

-

Donor and “innovative” financing models – from vertical disease programs to pooled funds, results-based financing, social impact bonds, and more.

Throughout, we keep a close eye on health systems innovation: changes in how care is delivered, financed, governed, digitized, and regulated, not just new gadgets or apps.

The lens is primarily African and Global South, but the lessons are relevant to any region wrestling with limited budgets, rising expectations, and a flood of new health technologies.

1. Understanding Health Systems Innovation in the Global South

1.1 From gadgets to systems thinking

“Health innovation” can mean very different things: a point-of-care diagnostic, a new vaccine, an AI triage tool, a telemedicine platform, a novel community health worker program, or a new way of contracting private providers. Increasingly, experts emphasise health systems innovation rather than isolated products—solutions that:

-

Improve service coverage and quality

-

Enhance financial protection

-

Strengthen governance, information systems, and supply chains

-

Reduce inequities across geography, gender, income, or disability

WHO frames health financing as central to UHC, highlighting the need to reduce out-of-pocket payments, expand prepaid pooled funds, and align incentives to improve quality and efficiency. World Health Organization Financing is therefore not just a “tap” that pours money into the system; it shapes which innovations are developed, which are scaled, and whose needs are prioritised.

1.2 The Global South realities: high needs, thin margins

For African and Global South countries, several structural realities shape the innovation financing landscape:

-

High disease burden: Persistent infectious diseases like malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, and vaccine-preventable illnesses, alongside NCDs and injuries.

-

Limited fiscal space: Many governments face high debt burdens, competing priorities (education, infrastructure, security), and limited ability to expand health budgets rapidly. Think Global Health

-

Dependent on external aid: While domestic health spending is growing in some countries, DAH remains indispensable for many priority programs. However, DAH growth has slowed, and donors increasingly push for “value for money” and co-financing. The Lancet

-

Small, fragile innovation ecosystems: Tech and startup ecosystems are growing, but still attract modest funding compared to other regions, and health is often seen as risky or politically sensitive. African startups overall attracted US$2.2 billion in 2024; health-tech is only a small share of this. Where Founders are Stars

-

Fragmented implementation: Multiple donors, vertical programs, and short-term projects can fragment planning and overburden ministries of health.

This context means that how financing instruments are designed—eligibility rules, reporting requirements, risk-sharing structures, and timelines—can either enable or undermine innovation.

2. Grants: The Foundation of Health Innovation Finance

Grants remain the backbone of health innovation funding in low-resource settings. They typically come from:

-

Bilateral and multilateral agencies (e.g., USAID, World Bank, Global Fund, Gavi)

-

Philanthropic foundations (e.g., Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust)

-

National research councils and innovation funds

-

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs and prize challenges

2.1 What grants do well

Grants are uniquely suited to:

-

Fund early-stage, high-risk ideas where commercial models are unproven.

-

Support public goods like surveillance systems, open-source tools, or data platforms.

-

Cross-subsidize equity goals, allowing innovators to serve low-income or remote populations.

-

Build institutions and capabilities, such as regulatory agencies, national digital health units, or community health worker (CHW) programs.

For example, USAID’s Development Innovation Ventures (DIV) has funded hundreds of health and development innovations across LMICs. Between 2010 and 2021, it awarded 252 grants across 47 countries, with nearly half at the piloting stage and only a small share (about 4%) supporting the transition to scale. Speaking of Medicine and Health This illustrates both the strength of grants in seeding pilots and their weakness in supporting scale-up.

Similarly, global funds like Gavi and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria use grant mechanisms not only to procure commodities (vaccines, medicines, bed nets), but also to strengthen health systems—financing cold chain equipment, data systems, and human resources. healthimplementation.undp.org+1

Gavi’s Health Systems and Immunisation Strengthening (HSIS) policy, updated in 2023, explicitly focuses on resilient and sustainable immunisation systems, supporting areas like data quality, supply chains, and community engagement. Gavi

2.2 Grants and health systems strengthening (HSS)

There is long-running debate about whether major global health funders have sufficiently supported HSS. Early evaluations found that some HSS windows were fragmented or poorly aligned with country priorities, though Gavi’s HSS window has evolved to address these issues. Center For Global Development

In recent years, cooperation between Gavi, the Global Fund, and the Global Financing Facility (GFF) has intensified around joint planning, malaria, and HSS. healthimplementation.undp.org+1 The rationale is clear: innovation in one disease area often depends on system-wide capabilities—such as cold chain, community outreach, and integrated data systems.

An example is the recent Gavi–UNICEF deal to reduce the price of the R21 malaria vaccine, which will extend coverage to an additional 7 million children over five years despite lower-than-expected replenishment funding. Reuters The price reduction itself is an “innovation in financing” (a market-shaping intervention) that unlocks more impact per dollar.

2.3 National and regional grant mechanisms

Beyond global initiatives, many African and Global South countries have established national innovation funds and research councils:

-

Kenya’s National Research Fund and Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) support local research and health innovation.

-

South Africa’s Medical Research Council (SAMRC) funds health research, including vaccine and diagnostic development.

-

Nigeria, Rwanda, and Ethiopia have set up various innovation and entrepreneurship funds, some with explicit health windows.

Regional programs—like the African Development Bank’s innovation finance initiatives or Africa-focused challenge funds—have also emerged, though often with small ticket sizes.

A 2024 concept note prepared for an Africa Health Business symposium on health financing in Africa emphasised the need for regional policy dialogues, increased budget allocations for health, and integrated funding approaches that combine domestic and external resources. Africa Health Business

2.4 Weaknesses and unintended consequences of grant funding

Despite their importance, grant-based models also have limitations:

-

Pilotitis: Grants often fund pilots and proofs-of-concept, but provide little support for the expensive and politically delicate work of integrating innovations into national systems. The DIV example—where only 4% of investments go to transition-to-scale—captures this gap. Speaking of Medicine and Health

-

Short time horizons: Many grants are three years or less, misaligned with the longer cycles needed for institutional and behavioural change.

-

Donor-driven priorities: Innovators may chase donor themes rather than responding to local health system priorities or user needs.

-

Heavy reporting requirements: Small, locally grounded organisations are often at a disadvantage compared to large international NGOs that can handle complex compliance.

-

Fragmentation: When multiple donors fund narrow projects in the same country, ministries of health can be overwhelmed by coordination and reporting demands.

Rethinking grant design is therefore essential: rather than funding one-off “innovative projects,” grants should explicitly support a pipeline from early-stage ideation through scale-up and institutionalisation, ideally in partnership with other forms of capital.

3. Seed Funds, Impact Investing, and the Health Innovation Pipeline

Grants alone cannot carry a promising innovation from idea to fully scaled solution. As solutions mature, they require capital that can fund growth, infrastructure, working capital, and sometimes cross-country expansion. For ventures with revenue potential—health-tech platforms, diagnostics manufacturers, insurance schemes—this often means equity, quasi-equity, or patient debt.

3.1 The African health-tech investment landscape

Overall African startup funding has declined from its 2021–2022 peak, but remains relatively resilient compared to some other regions. A 2025 analysis suggests African startups raised about US$2.2 billion in 2024, accounting for only 0.6% of global startup funding—and that health-tech represents a modest share of that total. Where Founders are Stars

A separate 2023 roundup by Salient Advisory found that investors with a mandate to invest in African health announced more than US$600 million in new funds in 2023, even as deal volumes slowed. salientadvisory.com This suggests that capital is available, but often struggles to find investable opportunities that meet impact and financial criteria.

Dedicated health-tech or impact funds—such as those focused on digital supply chains, last-mile delivery, or primary care—have emerged in cities like Nairobi, Lagos, and Cape Town. Equity ticket sizes, however, are often too large for early-stage innovators (e.g., US$1–5 million minimum), while seed-stage deals (US$50,000–250,000) remain under-supplied.

3.2 Seed funds, accelerators, and health innovation hubs

Seed funds and accelerators play a crucial role in bridging the gap between grants and commercial capital:

-

They offer small tickets (US$25,000–300,000) to test business models and product–market fit.

-

They provide non-financial support: mentorship, investor readiness, regulatory advice, and connections to health systems.

-

Some use blended finance, where grants cover technical assistance or first-loss capital, reducing risk for private co-investors.

Across Africa and the Global South, examples include:

-

Villgro and other health-focused incubators, which provide seed funding and technical support to med-tech and digital health startups.

-

Country-specific hubs in Kigali, Addis Ababa, Nairobi, Lagos, Accra, and Cape Town focusing on e-health, diagnostics, and logistics.

-

Global accelerators like MassChallenge, Plug and Play, and others that run specialised health-tech cohorts including African and South Asian startups.

Despite these efforts, there remains a “missing middle” of financing: early-stage ventures often struggle to transition from donor grants and pitch-competition prizes to recurring revenue and larger investment rounds.

3.3 Risk, return, and the realities of health markets

Health markets in Africa and the Global South present particular risks and constraints:

-

Regulatory and policy risk: Shifts in health insurance schemes, price controls, or import regulations can make or break a business model.

-

Payment delays: Selling to governments, donors, or large NGOs may involve slow payments and complex procurement.

-

Low purchasing power: Individually financed health services face affordability limits, especially for preventive care.

-

Currency and macroeconomic risk: Devaluations can erode returns for foreign investors.

At the same time, health ventures often deliver double bottom line returns—financial and social. Innovative financing structures like revenue-based finance, convertible grants, or patient capital with longer tenors can better align risk and impact expectations.

3.4 Case examples: Supply chains, diagnostics, and drone delivery

Several high-profile African health innovations illustrate the interplay of grants, equity, and donor contracts:

-

Drone delivery of health products: Companies like Zipline, operating in Rwanda and Côte d’Ivoire, have used a mix of donor support, government contracts, and private investment to build autonomous drone networks that deliver blood, vaccines, and medicines to remote facilities. ssir.org+1 In Côte d’Ivoire, Zipline now serves around 300 health facilities, helping to solve the “last mile” problem and reduce stock-out-related deaths. Le Monde.fr

-

Local diagnostics manufacturing: In Nigeria, Codix Bio is building a facility to produce HIV and malaria rapid test kits, supported by partnerships with international firms and expected demand from both the Nigerian government and global health donors, partly in response to reduced U.S. aid. Reuters This illustrates how shifts in donor funding can catalyse local industry, if financing and regulatory support align.

-

Digital health for CHWs: In Ethiopia, Malawi, and Sierra Leone, digital tools support community health workers with training, case management, and data reporting, often funded initially by grants and then progressively integrated into national systems. Last Mile Health+1

In each case, seed and growth capital interacts with grants and donor contracts. Drone delivery and diagnostics manufacturing rely heavily on government and donor procurement (quasi-public revenue), while digital CHW tools often start as donor-funded pilots and then transition to government ownership.

4. Donor and “Innovative” Financing Models

The phrase “innovative financing for health” covers a wide spectrum of instruments, from simple earmarked taxes to complex capital market products. A Lancet Global Health review defined innovative financing instruments as schemes that generate or mobilise funds in novel ways, often involving the private sector. The Lancet

4.1 Traditional vs. innovative financing

Traditional DAH involves grants or concessional loans from governments and multilaterals, typically channeled through projects or budget support. Innovative instruments include:

-

Solidarity levies and earmarked taxes – e.g., the airline ticket levy used by UNITAID, which raised hundreds of millions of dollars for HIV, TB, and malaria treatments.

-

Advance Market Commitments (AMCs) – guarantees from donors to buy a certain volume of a product (e.g., vaccines) at an agreed price if it is developed and meets specific criteria.

-

Pooled funds and trust funds – multi-donor vehicles that streamline contributions and fund large, multi-country programs (e.g., Gavi, the Global Fund, GFF).

-

Bonds and front-loading – such as the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), which issues bonds backed by long-term donor commitments.

-

Results-based financing (RBF) – payments linked to predefined outputs or outcomes, including performance-based financing schemes at facility level.

-

Social and Development Impact Bonds (SIBs/DIBs) – private investors finance interventions upfront and are repaid by donors or governments if outcomes are achieved.

-

Blended finance structures – combining grants, concessional loans, and commercial capital to de-risk investments in health infrastructure or enterprises. Harvard Public Health+1

A scoping review of social impact bonds in health found growing interest in applying them to NCDs, though evidence on effectiveness and efficiency is still limited and context-dependent. Harvard Public Health

4.2 What the evidence says about innovative financing

The Lancet review of innovative financing instruments from 2002–2015 concluded that such mechanisms mobilised roughly US$8.9 billion for health, mostly through UNITAID, IFFIm, and the Affordable Medicines Facility–malaria (AMFm). The Lancet However, it also noted that while these instruments can increase predictability and front-load resources, they do not necessarily expand overall donor willingness to pay.

A BMJ Global Health article on innovative financing for surgical systems highlighted the need for such mechanisms to prioritise equity and sustainability, avoid excessive complexity, and align with national priorities and capacities. BMJ Global Health+1

ThinkWell’s assessment of innovative finance for health for the G20 emphasised that these instruments should complement, not substitute, strong domestic financing and reforms in purchasing and pooling. ThinkWell

In the African context, WHO’s Regional Office for Africa and the Global Fund have convened regional technical meetings to explore innovative financing solutions, noting the importance of multi-sectoral collaboration, impact evaluation, and country-driven agendas. WHO | Regional Office for Africa

4.3 Donor models and health systems innovation

Donor models matter not just for how much money is available, but what kinds of innovation they incentivise:

-

Vertical disease programs can propel rapid innovation in specific areas (HIV, TB, malaria) but sometimes create parallel systems for procurement, data, and supply chains.

-

Sector-wide approaches and pooled funds (e.g., national health baskets) may be better for system-wide reforms and cross-cutting innovations like digital health or PHC strengthening.

-

RBF and performance-based aid can sharpen focus on results but may lead to gaming or neglect of non-measured areas if not carefully designed.

-

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) can bring in new investment and skills but require strong governance to avoid cost escalation or inequity.

For health systems innovation in Africa and the Global South, the most promising donor models:

-

Blend disease-specific and system-wide investments – for example, malaria vaccine funding accompanied by investments in cold chain, data systems, and CHWs.

-

Support locally led innovation ecosystems – funding not just isolated projects, but the hubs, accelerators, and regulatory bodies that sustain innovation.

-

Encourage domestic co-financing and ownership – to avoid “pilot dependence” and ensure long-term sustainability.

-

Use market-shaping and price-volume deals – like vaccine price reductions—to make innovations affordable at scale. Reuters+1

5. Health Systems Innovation in Practice: Case Studies

To make these financing dynamics concrete, consider several domains of health systems innovation that matter greatly in the Global South: community health, digital health, supply chains, and local manufacturing.

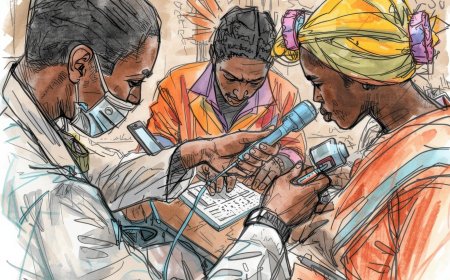

5.1 Community health workers (CHWs) and primary health care

CHW programs are a classic example of health systems innovation: they expand the health workforce, extend services to remote communities, and strengthen trust between health systems and communities.

Countries like Ethiopia, Uganda, and Malawi have scaled CHW programs significantly. The Africanica In Ethiopia, health extension workers serve rural populations using tools like electronic community health information systems (eCHIS), often supported by donor and grant financing. JSI Over time, digital tools for CHWs have been co-developed by ministries of health and partners to support training, decision support, and real-time data flows. Last Mile Health+1

Financing these programs typically involves:

-

Government salary budgets, sometimes with donor co-financing.

-

Grants for training, supervision, and digital tools.

-

Donor-funded pilots for new service packages (e.g., community case management of childhood illnesses, NCD screening).

-

Occasionally, results-based financing tied to coverage or quality indicators.

Sustaining CHW innovation depends on transitioning from project-based to line-item budget financing, with donor funds used strategically for upgrades (digitalisation, quality improvement) rather than basic operations.

5.2 Digital health platforms

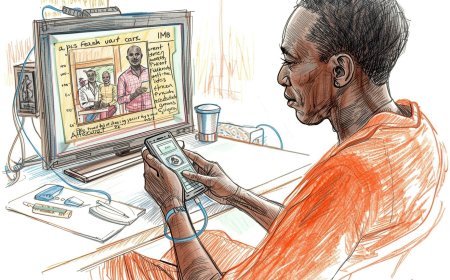

Digital health is one of the most visible arenas for innovation financing in Africa and the Global South:

-

Telemedicine and virtual care services.

-

mHealth apps for patient education and adherence.

-

Electronic medical records and hospital information systems.

-

Logistics and inventory management solutions.

-

Data analytics and AI decision-support tools.

Many digital health solutions start with grant funding from donors or foundations and are later tested as software-as-a-service products for governments or private providers. However, many pilots never move beyond grant cycles due to unclear business models, procurement bottlenecks, or lack of integration with national digital health architectures.

Evidence from countries like Ethiopia, Malawi, and Sierra Leone shows that digital tools for CHWs can improve training, documentation, and data use when integrated into national strategies and backed by sustained financing. Last Mile Health+1

Key financing lessons here include:

-

Donors should fund interoperability, standards, and governance (the “rails”) rather than an endless proliferation of stand-alone apps.

-

Governments and donors can use multi-year framework contracts to give digital providers predictable revenue.

-

Impact investors and seed funds can support early growth, but must align expectations with the realities of selling to public and donor markets.

5.3 Supply chains and last-mile delivery

Weak supply chains are a major barrier to health systems performance in the Global South. Innovations like autonomous drone delivery and digital logistics platforms are partially financed through:

-

Grants for R&D and early pilots (often from philanthropies and innovation funds).

-

Government and donor contracts for service delivery.

-

Equity investment for infrastructure, technology scale-up, and regional expansion.

Zipline’s operations in Rwanda and Côte d’Ivoire illustrate the potential and complexity of such models. Government contracts, backed in part by donor financing, pay per delivery, providing a revenue stream that can support private investment. ssir.org+1

Essential design questions include:

-

Are tariffs affordable for health systems in the long run?

-

How are subsidies structured, and who bears the risk as donor funds fluctuate?

-

How do such services integrate with broader supply chain reforms, rather than becoming a parallel track?

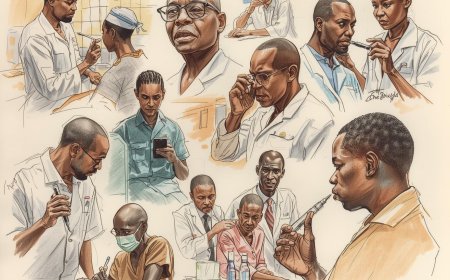

5.4 Local manufacturing and regional value chains

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the vulnerability of LMICs to global supply chain shocks, prompting renewed interest in local manufacturing of vaccines, diagnostics, and medicines.

The Nigerian case of Codix Bio’s new facility to produce HIV and malaria rapid tests illustrates how reduced external aid can create both challenges and opportunities. The plant, developed with support from WHO and international partners, aims to supply Nigeria and the broader West African region. Reuters

To finance such ventures:

-

Governments may provide land, tax incentives, or guaranteed procurement.

-

Donors and impact investors may offer blended finance, technical assistance, or risk-sharing.

-

Regional development banks can provide long-term loans for manufacturing infrastructure.

However, for local manufacturing to truly strengthen health systems, demand must be predictable (through long-term contracts or pooled procurement) and regulatory agencies must be capable of ensuring quality.

6. Designing Better Financing Instruments for Health Systems Innovation

Bringing these strands together, what does good financing for health innovation in Africa and the Global South actually look like? Several design principles stand out.

6.1 Match capital to the innovation lifecycle

Innovations move through stages: ideation, proof of concept, pilot, validation, scale-up, and integration. Different types of capital are appropriate at each stage:

-

Idea & early proof of concept

-

Research grants, challenge funds, and fellowships.

-

University and research-institute funding, often with bilateral or philanthropic backing.

-

-

Pilot and validation

-

Larger grants (e.g., DIV Stage 2, philanthropic catalytic grants). Speaking of Medicine and Health

-

Seed funding from impact investors and accelerators.

-

Outcomes-based grants that reward early evidence of effectiveness.

-

-

Scale-up and integration into systems

-

Blended finance models: grants plus equity or concessional debt. ThinkWell+1

-

Government and donor procurement contracts (e.g., framework agreements).

-

RBF and, in some cases, impact bonds tied to coverage or outcomes.

-

-

Mature operations and regional expansion

-

Commercial loans, private equity, and bonds for capital-intensive expansions.

-

Regional pooled purchasing and trade agreements for cross-border scale.

-

One of the biggest gaps in Africa and the Global South is financing for scale-up, where risk remains high but grants taper and investors demand clearer pathways to return. Deliberately building grant-to-equity “on-ramps”—for example, convertible grants or structured transition plans into outcome-based contracts—can help close this gap.

6.2 Align incentives with health outcomes and equity

Financing instruments shape behaviour. If grants reward shiny tech rather than verified health impact, or if investment terms encourage quick exits over long-term embedding in public systems, innovations may drift away from public health goals.

Key elements of good alignment include:

-

Clear, measurable health outcomes linked to funding tranches (e.g., coverage, quality, equity indicators).

-

Equity safeguards to ensure vulnerable populations benefit, not just urban elites.

-

Incentives for integration with national health strategies and digital architectures.

-

Transparency on pricing, margins, and subsidies, particularly in PPPs.

RBF and impact bonds offer one way to align financing with outcomes, but they must be carefully designed to avoid excessive transaction costs or perverse incentives. Harvard Public Health+1

6.3 Local ownership, “decolonized” funding, and governance

There is growing recognition that global health financing has often marginalised local actors and perpetuated unequal power dynamics. Rethinking innovation financing in Africa and the Global South therefore requires:

-

Locally led agenda-setting: National health and innovation strategies should define priorities, with donors aligning behind them.

-

Direct funding to local organisations and firms, not just international intermediaries.

-

Stronger domestic resource mobilisation, including tax reform and earmarked health revenues, to reduce over-dependence on external aid. Think Global Health+1

-

Regional collaboration, for example through African Union and regional economic communities, to develop shared regulatory standards, regional value chains, and pooled procurement.

Recent policy dialogues, such as the 2025 WHO Africa–Global Fund regional technical meeting on innovative financing, emphasise the need for multi-sector partnerships and more evidence-based decision-making, with African governments in the lead. WHO | Regional Office for Africa+1

6.4 Data, evidence, and learning loops

Any financing model is only as good as the evidence that informs its design and evolution. Priorities include:

-

Rigorous impact evaluation of grant-funded and innovative finance programs, not just success stories.

-

Comparable metrics across innovations to inform portfolio management—e.g., cost-effectiveness, scalability, equity impact, and health system integration.

-

Open data and knowledge sharing, especially across African and Global South contexts, to avoid reinventing the wheel.

Rethinking health innovation funding in Africa will require funders to take more calculated risks, but also to learn systematically from both successes and failures. Speaking of Medicine and Health+1

7. Regional Perspectives: Africa, South Asia, and Latin America

While this article focuses on Africa, similar financing dynamics play out across the Global South, offering opportunities for cross-regional learning.

7.1 Africa: Innovation amid fiscal constraints

Africa faces a combination of high health needs, constrained public budgets, and uneven donor support. A Think Global Health article by Zimbabwe’s finance minister highlights how debt burdens and fluctuating aid flows constrain public investment in health and innovation, arguing for better domestic resource mobilisation and smarter use of limited funds. Think Global Health

At the same time, African innovators are leading in areas such as:

-

Digital health platforms for chronic disease management and telemedicine. salientadvisory.com

-

Community-based primary care models and CHWs. The Africanica+1

-

Last-mile supply chain innovations, including drone delivery. ssir.org+1

-

Regional plans for vaccine manufacturing and diagnostics production. Reuters

The challenge is to build financing models that can sustain and integrate these innovations into public health systems, not just showcase them as isolated success stories.

7.2 South Asia: Scale, digital public goods, and insurance

South Asian countries, particularly India, offer lessons on leveraging scale and digital public infrastructure:

-

India’s Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission and health insurance scheme have created large-scale platforms that can incorporate private and public innovations in digital health, telemedicine, and health financing.

-

Social health insurance schemes in the region often purchase services from mixed public–private providers, creating opportunities for innovative delivery models.

Financing instruments include hybrid public–private insurance pools, PPPs, and outcome-based contracts, alongside traditional DAH and domestic budget allocations. These experiences can inspire African policymakers exploring national health insurance reforms and digital health architectures.

7.3 Latin America: Social protection and rights-based approaches

Countries like Brazil and Mexico have adopted rights-based, universal health systems (SUS and Seguro Popular/INSABI), financed predominantly from domestic tax revenues. While fiscal pressures and political cycles have challenged these systems, they show how domestic financing and legal entitlements can drive innovation in primary care, community participation, and integrated networks.

Innovative financing in Latin America has included:

-

Sin taxes (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, sugary drinks) earmarked for health.

-

PPPs in hospital infrastructure.

-

Use of conditional cash transfers and social protection schemes to influence health behaviours.

For Africa and the wider Global South, Latin American experiences highlight the value of constitutional and legal frameworks that anchor health as a right, providing a durable foundation for innovation even in the face of changing donor priorities.

8. Practical Guidance for Key Actors

To move from theory to action, it helps to consider what different stakeholders—governments, donors, investors, innovators, and civil society—can actually do.

8.1 Governments and ministries of health/finance

1. Develop a national health innovation and financing strategy

-

Define priority problem areas (e.g., primary care, NCDs, maternal health, surveillance, digital health, supply chain).

-

Map existing financing flows—domestic, donor, private—and identify gaps along the innovation lifecycle.

-

Establish principles for innovation financing: equity, integration, sustainability, local ownership.

2. Integrate innovation into core budgets, not just projects

-

Include line items for CHW programs, digital health infrastructure, and quality improvement.

-

Use domestically raised revenues and, where feasible, earmarked taxes (e.g., tobacco or alcohol) to fund innovation linked to NCD prevention.

3. Use purchasing power strategically

-

Design procurement to reward cost-effectiveness, interoperability, and local value creation.

-

Implement multi-year framework contracts for digital and service innovations, enabling providers to invest and scale.

4. Build capabilities for assessing value

-

Invest in health technology assessment (HTA) and economic evaluation to inform financing decisions.

-

Strengthen regulatory agencies and digital governance units to evaluate new technologies.

8.2 Donors and global health initiatives

1. Re-engineer grant portfolios to support the full innovation pipeline

-

Allocate explicit funding windows for transition-to-scale and system integration, not just pilots.

-

Simplify application and reporting workflows to increase access for local innovators and smaller organisations.

2. Align health innovation funding with country-owned plans

-

Support joint planning and funding compacts with governments, avoiding project fragmentation.

-

Fund regional public goods (standards, data platforms, regulatory networks) that underpin local innovation.

3. Use innovative finance judiciously

-

Employ AMCs, price-volume deals, and market-shaping to reduce costs of key innovations (e.g., vaccines). Reuters+1

-

Pilot RBF and impact bonds where outcomes are measurable and stakeholders have capacity, but avoid over-engineered instruments that increase transaction costs.

4. Shift power to local actors

-

Increase direct funding to local organisations and firms, with flexible, long-term support.

-

Support regional funds or platforms managed by African and Global South institutions.

8.3 Impact investors, seed funds, and venture capital

1. Design products for health, not just generic tech

-

Offer ticket sizes and instruments appropriate to health ventures—e.g., revenue-based finance, longer tenors, or blended structures.

-

Partner with donors who can provide first-loss capital, technical assistance, or guarantees. ThinkWell

2. Invest in “boring but essential” infrastructure

-

Logistics, digital platforms, and quality improvement tools may not be flashy, but they are critical for health systems.

3. Measure and report health impact transparently

-

Use standard metrics where possible (e.g., DALYs averted, service coverage, quality indicators).

-

Avoid “impact washing” by linking financing terms to independently verified outputs or outcomes.

8.4 Innovators and implementers

1. Start with the health system problem, not the technology

-

Co-design with ministries, providers, and communities to ensure relevance and adoptability.

-

Align with national strategies and digital architectures from the outset.

2. Build hybrid financing strategies

-

Combine grants (for R&D and evidence generation) with revenue-generating models (e.g., service contracts, licensing).

-

Plan early for how the innovation will be financed after donor support ends.

3. Document and share evidence

-

Invest in rigorous monitoring and evaluation, including cost-effectiveness where feasible.

-

Share results transparently, including challenges and failures, to inform funders and peers.

8.5 Civil society and communities

1. Hold funders and governments accountable

-

Track how innovation funds are allocated and who benefits.

-

Advocate for equity and community engagement in innovation design and financing.

2. Co-create and co-implement innovations

-

Community-based organisations bring trusted relationships and local knowledge that can make or break an innovation’s effectiveness.

9. Looking Ahead: Financing the Next Generation of Health Systems

Health systems in Africa and the Global South are at a critical juncture. The old model—largely dependent on external aid, focused on vertical disease programs, and reliant on project-based pilots—cannot deliver on the promise of UHC and resilience in an era of pandemics, climate shocks, and demographic change.

The emerging model must:

-

Blend domestic and external resources, with a gradual shift toward greater domestic financing.

-

Combine grants, seed funds, and innovative financing instruments in a coherent pipeline that supports the entire life cycle of health innovations.

-

Centre health systems innovation, not just individual technologies, and ensure that financing instruments reward integration, equity, and long-term impact.

-

Elevate local leadership, knowledge, and institutions, including regional platforms in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.

Recent developments—from regional meetings on innovative financing in Africa WHO | Regional Office for Africa to expanding African manufacturing capacity Reuters—show that the ingredients are coming together. What is needed now is deliberate design: financing architectures that connect the dots between ideas, investments, and institutional change.

For African and Global South policymakers, funders, and innovators alike, the next decade will determine whether financing is a brake or an accelerator on health systems innovation. The choices made today—about who pays, how, and for what—will shape not only the trajectory of health innovation, but the lives and futures of hundreds of millions of people.

References

Note: URLs are provided via citations above; years reflect publication or latest update where available from sources.

African Health Business. (2025). Leveraging innovation financing for health to advance UHC in Africa (Symposium concept note). Africa Health Business

Disrupt Africa. (2024). The African tech startups funding report 2023. Disrupt Africa

Founders Africa. (2025, February 2). African startups secured $2.2B in 2024 – Funding trends & key insights. Where Founders are Stars

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. (2025). Health system and immunisation strengthening (HSIS) policy. Gavi

Glassman, A., & Silverman, R. (2017). Gavi’s approach to health systems strengthening: Reforms for enhanced effectiveness. Center for Global Development. Center For Global Development

Global Fund, Gavi, & World Health Organization. (2023). Impactful partnership in action: Global Fund, Gavi and WHO. The Global Fund+1

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2023). Innovative financing (Health Systems Innovation Lab). Harvard Public Health

Last Mile Health. (2024, November 1). Three digital health innovations helping community health workers deliver quality care. Last Mile Health

Mishra, S., et al. (2020). Innovative financing to fund surgical systems and expand surgical care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health, 5(6), e002375. BMJ Global Health

Salient Advisory. (2024). 2023 roundup: Investments in African healthtech. salientadvisory.com

Seelos, C., Sofer, M., Burton, C., & Mair, J. (2024). Zipline drone delivery offers lessons for health care innovation in Africa. Stanford Social Innovation Review. ssir.org

Think Global Health. (2025). Financing health innovation in Africa. Council on Foreign Relations. Think Global Health

ThinkWell. (2020). Innovative financing mechanisms for health. ThinkWell

UNDP. (2024). Gavi and the Global Fund – Health implementation manual. healthimplementation.undp.org

USAID Development Innovation Ventures. (2024). Rethinking health innovation funding in Africa for maximum impact. PLOS Speaking of Medicine & Health (blog). Speaking of Medicine and Health

World Health Organization. (2025). Health financing. World Health Organization

World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. (2025, September 23). Fourteen African countries explore innovative financing solutions for health in the African region. WHO | Regional Office for Africa

Zipline & Government of Côte d’Ivoire. (2025). La Côte d’Ivoire développe la livraison de produits de santé par drones [News article]. Le Monde.fr

JSI. (2024). A community health worker’s dedication, strengthened through innovation [Story]. JSI

Reuters. (2025, June 19). Nigerian company to make HIV, malaria test kits after US funding cut. Reuters

Reuters. (2025, November 24). Gavi, UNICEF sign deal to cut malaria vaccine price. Reuters

The Africanica. (2025). Revolutionizing healthcare: African innovations changing lives in 2025. The Africanica

The Lancet Global Health. (2017). Innovative financing instruments for global health 2002–15: A systematic review of their characteristics and effects. The Lancet

FundsforNGOs. (2025). 50+ grant opportunities for health projects in Africa (listing). Funds for NGOs

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0