Decolonizing Global Health in the Age of Digital Transformation: Rethinking Aid and Partnerships as Africa Leads Its Future

This paper explores how the surge of digital transformation in health care intersects with the global movement to decolonize global health, especially in the African context. It critically examines power asymmetries in aid and partnerships, the legacies of colonialism in global health governance, and how Africa’s leadership—through digital innovation, data sovereignty, pharmaceutical sovereignty, and reimagined global partnerships—can reshape health equity.

Introduction

The 21st century has witnessed a profound transformation in global health driven by digital technologies: mobile health applications, telemedicine, health informatics, and artificial intelligence (AI) promise to connect populations, optimize care delivery, and improve outcomes. Yet, as these technologies proliferate, there is growing concern that they may reinforce rather than dismantle historical inequities rooted in colonialism, especially in low- and middle-income regions such as Africa (Corrales Compagnucci, 2025). The movement to decolonize global health has gained traction in recent years as scholars, practitioners, and policymakers critique the ways in which power asymmetries, funding structures, and knowledge production continue to reflect colonial patterns (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023; Tagoe et al., 2025). As Africa leads its own digital health future, it is essential to rethink traditional paradigms of aid, partnerships, and governance to ensure equitable, locally grounded, and sovereign health systems.

In this secondary research paper, I examine how the digital transformation of global health interacts with decolonization efforts, with a special focus on Africa’s evolving role. I analyze the structural and epistemic challenges, highlight emerging African-led models, and propose a framework for reimagining aid and partnerships that centers African agency.

This paper is structured as follows:

-

Conceptual foundations: decolonization, digital health, and power in global health

-

Historical legacy: colonialism and global health’s architecture

-

Digital transformation in African health systems: promise and pitfalls

-

The risk of coloniality in digital health

-

African-led innovations and sovereignty: data, pharmaceuticals, governance

-

Rethinking global aid and partnerships for a decolonized future

-

Policy recommendations and framework

-

Conclusion

1. Conceptual Foundations

1.1 Decolonization in Global Health

The call to decolonize global health challenges entrenched power asymmetries that mirror colonial hierarchies: decision-making, funding, and research are often dominated by high-income countries (HICs), while low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including many in Africa, remain recipients rather than equal partners (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023). Scholars identify several dimensions of colonialism in global health:

-

Colonialism within global health – power imbalances in partnerships, where Northern institutions hold disproportionate influence over agenda setting, resource allocation, and implementation.

-

Colonisation of global health – the dominance of Western epistemologies, methodologies, and knowledge hierarchies that marginalize local perspectives.

-

Colonialism through global health – how global health as a field perpetuates neo-colonial structures via intellectual property regimes, procurement practices, and governance (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023; Tagoe et al., 2025).

To decolonize global health, it is not enough to adopt equity checklists or improve representation; significant structural transformation is needed: shifting decision-making authority, redistributing resources, and holding power holders accountable (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023).

1.2 Digital Transformation and Global Health

Digital transformation in health refers to the integration of digital technologies — such as telemedicine, mobile health (mHealth), AI, health information systems, and interoperability standards — into health systems to improve the accessibility, quality, and efficiency of care (Corrales Compagnucci, 2025). These transformations are often hailed for their potential to leapfrog infrastructure gaps, especially in resource-constrained settings.

However, digital health is not inherently equitable: governance, data control, and infrastructure reflect existing inequalities. Without careful design and regulation, digital tools may exacerbate disparities rather than bridge them.

1.3 Power, Sovereignty, and Partnerships

In rethinking global health for a decolonized, digital era, three interlinked concepts are central:

-

Sovereignty: This includes data sovereignty (control over health data), pharmaceutical sovereignty (local production and access), and regulatory sovereignty (local capacity to govern digital health).

-

Partnerships: How global health partnerships are structured, including who sets priorities, who designs and implements interventions, and how benefits and risks are shared.

-

Power: The dynamics of power in global health funding, knowledge production, and technology development.

A decolonial framework must center African agency in all three domains.

2. Historical Legacy: Colonialism and Global Health Architecture

2.1 Colonial Origins of Global Health

Modern global health has roots in colonialism: during the colonial era, European powers introduced public health systems in their colonies primarily to protect colonial administrators and economic interests. These systems were often extractive, vertical, and externally driven, focusing on diseases that threatened colonial economies rather than local health priorities (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023).

The postcolonial global health architecture continued many of those patterns. International funding, research institutions, and high-level decision-making remained concentrated in the Global North, perpetuating a cycle of dependency (Tagoe et al., 2025).

2.2 Power Asymmetry in Research and Funding

Research partnerships often reflect significant power imbalances: funders and institutions in high-income countries design studies, set agendas, and retain intellectual property, while LMIC partners contribute data collection but have limited influence in knowledge production (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023; Tagoe et al., 2025). This perpetuates epistemic injustice, where local knowledge systems and priorities are undervalued.

Additionally, funding models can encourage extraction: LMICs may rely on foreign grants that are not aligned with local priorities, undermining long-term capacity building. Scholars argue for redistribution of resources and local leadership in global health research (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023).

2.3 Global Health Governance and Coloniality

Global health governance institutions (e.g., WHO, multilateral donors) often reflect colonial-era power structures. Decision-making, standard setting, and resource allocation are heavily influenced by wealthy donor countries, limiting the capacity for LMICs to assert sovereignty (Tagoe et al., 2025).

Moreover, procurement and intellectual property regimes, such as those governing pharmaceuticals, are still structured to favor external producers. Africa’s reliance on imported medicines and vaccines is a legacy of colonial extraction intensified by structural adjustment policies and intellectual property protections (Mulumba, Oga, Koomson et al., 2025). These systems undermine local production and contribute to dependency.

3. Digital Transformation in African Health Systems: Promise and Pitfalls

3.1 The Promise of Digital Health in Africa

3.1.1 Scaling Access and Bridging Gaps

Digital health offers the promise of addressing long-standing access challenges in African health systems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital tools played a critical role: a UN report describes how Burkina Faso’s Ministry of Health leveraged the CommCare platform to rapidly deploy COVID-19 modules to frontline health workers. The success was due to existing scale, governmental champions, and strong partnerships (UN, 2023). United Nations

Moreover, investments in interoperable systems can help integrate fragmented health information systems, enabling better continuity of care and data-driven decision-making.

3.1.2 Strengthening Health Workforce and Infrastructure

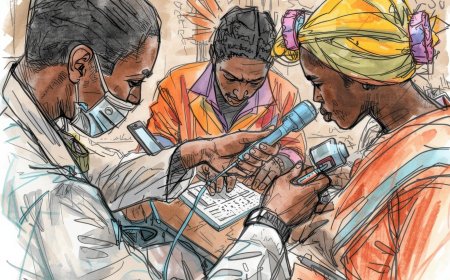

Digital health can support capacity building. For instance, the WHO Regional Office for Africa (WHO/AFRO) signed a cooperation agreement with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to build interoperable platforms, train digital health workforces, and engage telecommunications partners (WHO/AFRO-ITU, 2017). WHO | Regional Office for Africa

A concrete African-led initiative is "Africa on FHIR," championed by the Health Informatics in Africa (HELINA) network, Africa CDC, HL7 International, WHO, and other stakeholders. The initiative builds capacity in the use of HL7 FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) standards, thereby promoting standards-driven digital health transformation across the continent. helina.africa

3.1.3 Innovation, Sovereignty, and Local Agency

Digital transformation can enable greater African autonomy. By controlling their health data architecture, regulation, and implementation, African states can reduce dependency on external actors. The African Union (AU) and Africa CDC have expressed commitment to homegrown, digitally enabled health innovation aligned with Agenda 2063. African Union+1

3.2 The Pitfalls: Digital Coloniality

Despite the promise, digital transformation in global health is not neutral. Without intentional decolonial frameworks, it can entrench colonial power dynamics.

3.2.1 Data Governance and Sovereignty

In much of Africa, health data—collected locally—may be stored on servers owned by multinational corporations or subject to foreign jurisdictions, undermining data sovereignty. Corrales Compagnucci (2025) emphasizes the importance of reimagining digital health governance (DHG) to address such power imbalances. petrieflom.law.harvard.edu

Lack of governance can lead to exploitation: data extracted without robust protections, without local control, or without meaningful consent perpetuates colonial extraction in a digital form.

3.2.2 Ethical Disjunctures and Cultural Mismatch

AI ethics frameworks are often developed in the Global North and reflect Western values such as individualism and autonomy. These may not align with communalist and relational worldviews more common in many African societies (e.g., Ubuntu). SpringerLink

Without culturally grounded frameworks, digital health tools risk ethical misalignment, lack of trust, and reduced relevance to local contexts.

3.2.3 Commercialization and Fragmentation

Rapid digital health adoption, especially through private-sector actors, may encourage commodification of health, raising equity concerns (Corrales Compagnucci, 2025). petrieflom.law.harvard.edu The drive for profits may overshadow the public good.

Additionally, fragmented systems without interoperability may result in silos, duplicative tools, and inefficiencies. Without standards, digital health may replicate colonial-era fragmentation rather than heal it.

3.2.4 Resource and Funding Dependence

Digital health projects in Africa are often funded by external donors. However, reliable data on the real cost of digital transformation is limited, making it challenging for LMIC governments to plan long-term investments. Transform Health Coalition notes that while 60–70% of digital health funding needs could potentially be covered by domestic sources, the remainder still relies heavily on multilateral donors, development banks, and other external partners. Transform Health

This dependence undermines sustainability and local leadership, perpetuating patronage rather than partnership.

4. Risk of Coloniality in Digital Health: A Decolonial Lens

To fully apprehend the risk that digital health may reinforce coloniality, one must apply a decolonial analytical lens.

4.1 Coloniality of Power and Digital Technologies

The concept of coloniality of power (Quijano, 2000) refers to the persistence of colonial-era social and economic hierarchies, even after formal decolonization. In the digital age, this persists through who owns, governs, and benefits from technology.

For example, AI systems trained on data from African populations may still be developed, controlled, and monetized by Northern institutions, reinforcing power inequities. A study by Asiedu et al. (2024) found that participants identified colonial history, country of origin, and national income as axes of AI bias in health systems. arXiv

4.2 Epistemic Injustice and AI Ethics

AI ethics frameworks often reflect Western philosophical traditions. In Africa, ethical perspectives are influenced by communalism, relationality, and context-specific understandings of care and responsibility (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023). The disjuncture can lead to misalignments in how fairness, consent, accountability, and harm are conceptualized (Ong’era Mogaka & Stewart, 2023; turn0search3).

Decolonizing AI ethics involves centering African values and participatory processes, co-creating frameworks with communities, and ensuring algorithms are contextually validated (turn0search3).

4.3 Governance and Consent

Digital health governance must contend with the question: Who controls data? Where is it stored? Under whose laws? Corrales Compagnucci argues for a multi-faceted governance model that emphasizes equity, consent, and shared accountability. petrieflom.law.harvard.edu Without such models, health data may become a new frontier of neo-colonial extraction.

4.4 Structural Dependence and Commercialization

Commercial actors (tech companies, platform providers) often play a dominant role in digital health in Africa. While private sector involvement can accelerate innovation, it can also skew priorities toward market-driven models rather than public good. The risk is that digital health becomes a tool of profit rather than justice (Corrales Compagnucci, 2025).

Moreover, fragmented investments funded by external actors can sideline national health strategies, undermining sovereignty.

5. African-led Innovations and Sovereignty: Shifting the Paradigm

Despite the risks, Africa is not a passive recipient of digital health: many actors are asserting sovereignty, innovation, and leadership, offering decolonial alternatives.

5.1 Data Sovereignty and Governance

African stakeholders are beginning to build data governance models that center sovereignty and accountability. For instance, the push for interoperable standards (e.g., Africa on FHIR) reflects a desire to own the data architecture of health systems (HELINA, Africa CDC) rather than rely on externally imposed platforms. helina.africa

Decolonial governance also insists on community participation, transparency, and mechanisms for feedback and redress (Corrales Compagnucci, 2025).

5.2 Pharmaceutical Sovereignty

The quest for pharmaceutical sovereignty is a key strategy in decolonizing global health. Mulumba, Oga, Koomson, Kara, Cynthia, and Forman (2025) highlight how Africa’s dependency on imported medicines and intellectual property regimes undermines health equity. BioMed Central+1

They identify four major barriers: patent exclusivities, immature regulatory capacity, under-investment, and import-biased procurement. Overcoming these requires synchronized action: regulatory harmonization through the African Medicines Agency (AMA), pooled procurement, technology transfer partnerships, and civic engagement (Mulumba et al., 2025).

Their analysis shows that pharmaceutical sovereignty is not just political rhetoric but operationally achievable.

5.3 Research Ecosystems and Knowledge Production

Decolonial action in global health research involves transforming whose voices, knowledge systems, and institutions count. Tagoe, Abimbola, Bilardi, Kamuya, Gilson, Molyneux, and Atuire (2025) propose a mapped health research ecosystem that centers African institutions, local priorities, and rebalanced funding structures. BioMed Central

They recommend both incremental and radical reforms in five domains: knowledge production, funding, education, tool development, and uptake. These reforms aim to dismantle epistemic hierarchies and build locally rooted research capacity.

5.4 Ethical AI and Communal Contexts

Decolonizing AI ethics in Africa’s healthcare involves rethinking principles such as fairness, inclusion, justice, and beneficence through communalist lenses. The work by African ethicists suggests that frameworks grounded in relationality, community benefits, and shared responsibility better reflect African values (turn0search3).

Furthermore, algorithm development and validation should be participatory, context-sensitive, and accountable to local communities (turn0search3).

5.5 Continental Strategies: Africa CDC and AU Leadership

Institutionally, Africa is advancing its digital health sovereignty. Africa CDC’s Digital Transformation Strategy (2023) aligns with the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and underscores the importance of interoperable systems, digital health workforce capacity, and continental leadership. Dala Group

Also, at the AU level, leaders have reaffirmed commitment to homegrown, cost-effective, digitally enabled innovations. In a high-level event on World Health Day 2025, AU stakeholders highlighted the need for locally led digital health innovation (turn0search9).

6. Rethinking Aid and Partnerships for a Decolonized Digital Health Future

To support a decolonized global health ecosystem in an era of digital transformation, global aid and partnerships must be fundamentally rethought.

6.1 Principles of Decolonial Partnerships

Based on the literature, the following guiding principles emerge:

-

Subsidiarity and agency: African partners should lead in setting priorities, designing digital health solutions, and governing data.

-

Equity in decision-making: Partnerships should share power in governance structures, funding decisions, and accountability.

-

Long-term capacity building: Rather than short-term pilots, aid should support sustainable infrastructure, workforce development, and regulatory systems.

-

Data and technology sovereignty: Support should be for architectures and platforms that local stakeholders control, not lock-in to proprietary external systems.

-

Mutual accountability: Partners should be accountable to local communities, not just donors, with mechanisms for redress and evaluation.

-

Ethical co-creation: Digital health interventions should be co-designed with local communities, respecting cultural values, and embedding ethics from the start.

6.2 Reforming Funding Models

Traditional donor models must shift:

-

Flexible funding: Grants should support core digital infrastructure, interoperable standards (e.g., FHIR), and capacity building.

-

Pooled financing: Continental mechanisms (e.g., African Development Bank, AU funds) could co-invest in digital health, reducing dependency.

-

Risk-sharing partnerships: Encourage venture philanthropy, social investment, and public–private co-investments, aligned with public health goals.

-

Investment in sovereignty: Support technology transfer, capacity for local software development, and regional regulatory harmonization.

6.3 Strengthening Governance and Regulation

To ensure digital transformations align with decolonial aims:

-

Regulatory institutions: Support and strengthen continental and national bodies like Africa CDC, AMA, and digital health authorities to regulate data, AI, and technologies.

-

Standards adoption: Promote interoperable standards (e.g., FHIR) to avoid fragmentation and vendor lock-in.

-

Ethical frameworks: Co-create AI ethics frameworks rooted in African values and governance practices.

-

Data governance frameworks: Develop policies for data ownership, consent, sharing, and reuse that protect local sovereignty.

-

Community accountability: Institutionalize mechanisms that allow communities to provide input, give feedback, and seek redress regarding digital health tools.

6.4 Building Research and Knowledge Ecosystems

Strong partnerships must nurture African-led research:

-

Funding to African institutions: Prioritize grants that flow directly to African research institutions, not just through Northern partners.

-

Capacity building: Invest in training for health informatics, AI, bioethics, and data governance.

-

Knowledge co-production: Encourage co-leadership in research design, implementation, and dissemination.

-

Peer networks: Support networks such as the Decolonisation and Global Health Research Exchange to facilitate exchange and collective action (Tagoe et al., 2025).

7. Policy Recommendations & Framework for Action

Based on the analysis above, I propose a decolonial digital health policy framework that African governments, regional bodies, donors, and partners can adopt.

| Domain | Goal | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Governance & Regulation | Sovereign digital health systems | - Establish or strengthen national/regional digital health authorities - Adopt interoperable standards (e.g., FHIR) - Create data governance policies prioritizing data sovereignty |

| Funding & Partnerships | Equitable, sustainable investment | - Set up continental pooled digital health fund - Encourage blended financing (public, private, philanthropic) - Shift donor funding to support core infrastructure, not just pilots |

| Ethics & Community Engagement | Contextual, inclusive innovation | - Develop community-informed AI ethics frameworks - Ensure participatory design and consent in digital health interventions - Build accountability mechanisms (feedback, redress) |

| Research & Knowledge | African-led knowledge production | - Fund African-led digital health research - Invest in capacity building (informatics, AI, governance) - Support knowledge networks and co-creation platforms |

| Pharmaceutical & Data Sovereignty | Reduce external dependency | - Support local pharmaceutical production via technology transfer - Harmonize regulation through bodies like the African Medicines Agency (AMA) - Build platforms for sovereign data storage and processing |

8. Challenges and Risks to the Proposed Framework

While the above framework outlines a hopeful and just future, real-world challenges must be acknowledged.

-

Resource constraints: Many African governments may lack the fiscal space to invest in digital infrastructure or regulatory bodies.

-

Political will and governance: Power dynamics between national governments, regional bodies, and donors may impede aligned action.

-

Capacity gaps: There may be insufficient trained workforce (health informaticians, digital health regulators, data scientists) to operationalize the framework.

-

Commercial resistance: Private companies may resist interoperable standards or data sovereignty policies if they threaten profit models.

-

Fragmented donor agendas: Donors may continue funding project-based approaches rather than system-level, long-term investments.

To mitigate these risks, coordinated advocacy, capacity-building, and Southern-led institution building are vital. The role of regional bodies like the AU, Africa CDC, and AMA is crucial in convening stakeholders, aligning strategies, and mobilizing resources.

Conclusion

The intersection of digital transformation and decolonizing global health presents both opportunity and peril. Without intentional action, digital health may replicate colonial hierarchies through data extraction, external control, and profit-driven models. Yet, Africa is not a passive observer: the continent is actively shaping its future through digital sovereignty, pharmaceutical production, ethical innovation, and new partnership paradigms.

Decolonizing global health in the digital age requires a fundamental reimagining of aid, governance, and agency. The proposed decolonial framework centers African leadership — through data governance, research ecosystems, regulatory institutions, and ethical co-creation. It calls on donors, governments, regional bodies, and civil society to shift from extractive models toward equitable, long-term, accountable partnerships.

As Africa leads its future, the global health community must reconcile digital ambition with justice. Only then can digital transformation become a tool of liberation, not colonization.

References

Asiedu, M., Dieng, A., Haykel, I., Rostamzadeh, N., Pfohl, S., Nagpal, C., Nagawa, M., Oppong, A., Koyejo, S., & Heller, K. (2024). The case for globalizing fairness: A mixed methods study on colonialism, AI, and health in Africa. arXiv. arXiv

Bankole, F. O., & Mimbi, L. (2016). ICT and health system performance in Africa: A multi-method approach. arXiv. arXiv

Corrales Compagnucci, M. (2025, June 16). Decolonizing Digital Health: Reclaiming Equity, Consent, and Governance in Global Health Innovation. Petrie-Flom Center. petrieflom.law.harvard.edu

Mulumba, M., Oga, J., Koomson, N., Kara, T.-A., Cynthia, A. N., & Forman, L. (2025). Decolonizing global health: Africa’s pursuit of pharmaceutical sovereignty. BMC Health Services Research, 25(1015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-13211-9 BioMed Central

Ong’era Mogaka, F., & Stewart, J. (2023). Global Health: Building better practices for equitable collaborations and decolonizing global health (ICRC Toolkit). International Clinical Research Center. HCMCIM

Roberts, J. S., & Montoya, L. N. (2022). Decolonisation, global data law, and Indigenous data sovereignty. arXiv. arXiv

Tagoe, N., Abimbola, S., Bilardi, D., Kamuya, D., Gilson, L., Molyneux, S., & Atuire, C. (2025). Creating different global health futures: mapping the health research ecosystem and taking decolonial action. BMC Health Services Research, 25(565). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-12566-3 BioMed Central

Tshimuila, J. M., Kalengayi, M., Makenga, D., Lilonge, D., Asumani, M., Madiya, D., … & Kasoro, N. M. (2024). Artificial intelligence for public health surveillance in Africa: Applications and opportunities. arXiv. arXiv

World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa & International Telecommunication Union. (2017). The transformation: Cooperative agreement on digital health services. WHO/AFRO & ITU. WHO | Regional Office for Africa

African Union Commission. (2025, April 23). Africa reaffirms commitment to health innovation: strengthening systems for sustainable development. AU Press Release. African Union+1

Health Informatics in Africa (HELINA), Africa CDC, HL7 International, & WHO. (n.d.). Africa on FHIR – Empowering the ecosystem. HELINA. helina.africa

Transform Health Coalition. (2023, October). Closing the digital divide: Africa brief. Transform Health

UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa. (2023). Digital health and COVID-19 in Africa. United Nations. United Nations

AI & Ethics. (2025). Decolonizing AI ethics in Africa’s healthcare: An ethical perspective. AI and Ethics, 5(3129–3142). SpringerLink

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0