African Pharmacies: The Next Frontier in Primary Care

Pharmacies are uniquely placed to expand primary care in Africa. Practical roadmap for integrating pharmacies into health systems through training, regulation and financing.

Across African cities, towns and villages, there’s a health asset too often overlooked: the neighbourhood pharmacy. They open early, close late, sit at market corners and main roads, and are frequently the first place people go when someone is ill. For many families, the local pharmacy is more accessible than a clinic, less intimidating than a hospital, and already embedded in daily life. That proximity and trust make pharmacies an untapped frontier for expanding primary care — if we reimagine their role and back them with the right training, regulation and financing.

Why pharmacies? Three simple reasons.

First, access. There are far more pharmacies than primary-care clinics in many settings, and they are distributed in underserved peri-urban and rural areas. Second, trust and continuity: community pharmacists often know their customers and their households, giving them relational continuity that is central to primary care. Third, speed and convenience: pharmacies meet people where they are — on their way to work, at the market, or after hours — making them ideal for early diagnosis, chronic disease follow-up, and simple preventive services.

Turning this potential into reality, however, requires deliberate shifts — not a wholesale replacement of clinics but an expansion of the primary-care ecosystem. Here’s a practical roadmap.

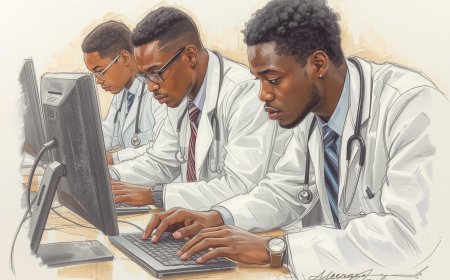

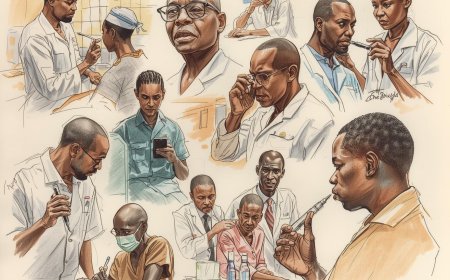

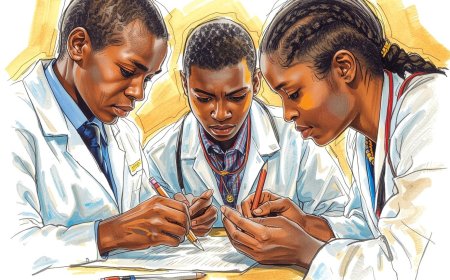

1. Re-skill and professionalize pharmacy practice

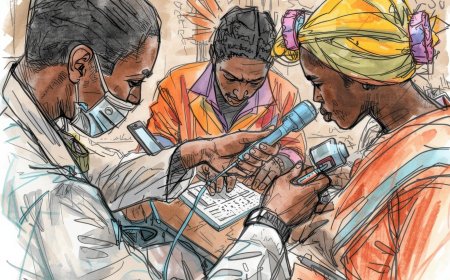

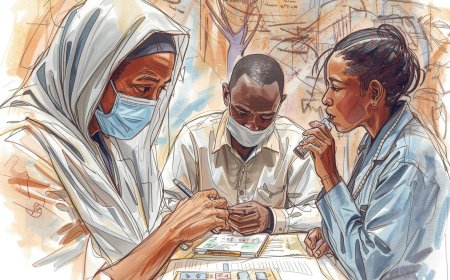

Pharmacists should be trained and certified to deliver a defined package of primary-care services: symptom triage, treatment for common ailments, point-of-care testing (malaria, HIV, glucose, HbA1c, pregnancy), basic wound care, immunizations where legal, adherence counseling for chronic disease, and medication therapy management. Short, modular training programs — combined with continuous professional development and mentorship — can build capacity rapidly.

2. Create clear regulatory frameworks and referral pathways

Regulators must define what pharmacies can safely do and how they should refer complex cases. Clear scopes of practice, standardized screening protocols, and simple referral forms will prevent scope creep while enabling pharmacists to treat and refer with confidence. Legal protection and supervision structures will encourage responsible task-shifting.

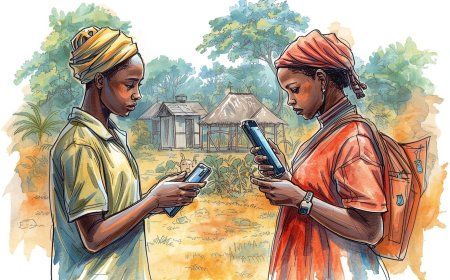

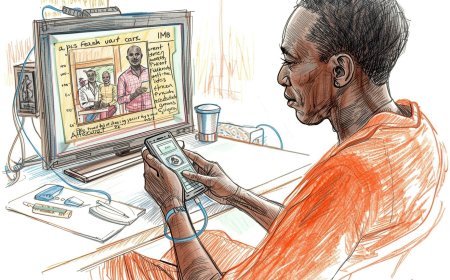

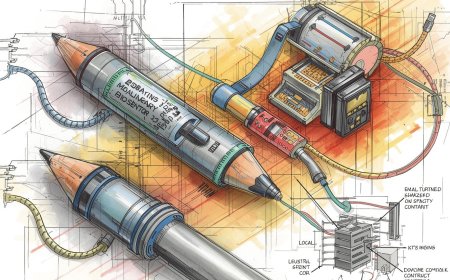

3. Equip pharmacies with point-of-care diagnostics and digital tools

Affordable diagnostic kits and simple electronic records (even low-bandwidth mobile apps) let pharmacists make better, evidence-based decisions and document care. Digital referrals and teleconsultation links to clinicians can handle the trickier cases without destabilizing the local clinic. Data collected at pharmacies should feed into national health information systems to improve surveillance and planning.

4. Align financing and incentives

Current payment models often leave pharmacies reliant on medicine sales, which can skew behaviors. Blended financing — small fees for consultation, outcome-based payments for chronic disease management, or government reimbursements for basic services — can realign incentives toward quality care. Insurance schemes and public purchasing should include accredited pharmacies as contracted providers.

5. Strengthen supply chains and quality assurance

Pharmacies must have reliable access to quality medicines and supplies. Strengthening procurement pools, track-and-trace systems, and quality-inspection capacity reduces counterfeit risk and stockouts, protecting patients and reputation. Accreditation programs and routine audits promote standards without being punitive.

6. Foster partnerships with clinics and communities

Pharmacies should not act in isolation. Formal linkages — MOUs with clinics, joint community outreach, and shared continuing education — build mutual trust and create shared care pathways. Community engagement ensures services meet local needs and respects cultural norms.

7. Protect equity and affordability

Expanding pharmacy-led care must not create two-tier access. Policymakers should ensure subsidized services for low-income populations, include pharmacies in public insurance schemes, and monitor costs. Sliding-scale fees, vouchers, or government reimbursements can keep essential services affordable.

A checklist for scaling pharmacy-led primary care

-

Define a minimum primary-care package pharmacies can deliver.

-

Implement modular training + certification for pharmacists and pharmacy assistants.

-

Establish legal scopes of practice and explicit referral protocols.

-

Pilot point-of-care diagnostics and a lightweight digital record that syncs with national systems.

-

Create payment mechanisms that reward quality (consultation fees, capitation, or outcome payments).

-

Set up accreditation, supply chain safeguards, and periodic audits.

-

Include pharmacies in public health campaigns (immunization drives, screening days).

Who should act — and how

Policymakers: Update regulations to enable safe task-shifting, integrate pharmacies into public contracting, and include them in national health strategies.

Regulators: Build accreditation and quality frameworks that are supportive and capacity-building.

Funders & investors: Finance training, digital tools, and supply-chain modernization; pilot innovative reimbursement models.

Pharmacists & associations: Lead on standards, embrace training, and build referral relationships with clinics.

Clinicians: Partner on supervision, teleconsultation and shared care protocols to maintain quality and continuity.

Why this matters now

African health systems face stretched budgets, rising chronic disease burdens, and persistent geographic gaps in access. Pharmacies offer a pragmatic, lower-cost way to expand primary care reach rapidly. Done right, pharmacy-led primary care can shorten time to treatment, improve chronic disease control, reduce unnecessary hospital visits, and strengthen disease surveillance. It is not a panacea — clinics and trained clinicians remain essential for complex care — but integrating pharmacies into the primary-care architecture multiplies the system’s capacity where people already seek help.

This is a moment to be bold yet practical. Reimagining pharmacies as community primary-care hubs is one of those high-leverage moves: it builds on existing infrastructure, meets people where they are, and can produce measurable gains fast. For entrepreneurs, regulators and funders ready to pivot from isolated pilots to system-facing investments, pharmacies are the next frontier—and one that could reshape primary care across the continent.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0