The Beautiful Funeral: A Founder's Guide to Grief, Ghosts, and Rebirth in African Entrepreneurship

An in-depth exploration of entrepreneurial failure on the African continent, tailored to an African audience. This report delves into the profound, often silent, grief that accompanies business failure, contrasting the global "fail fast" mantra with the harsh cultural realities in Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, and Kenya. Through witty anecdotes, proverbs, and real-world case studies from the medical and healthcare industries, including a post-mortem of 54Gene, it examines the psychological trauma, public shame, and the unique societal pressures founders face. The report serves as both an autopsy of business death and a practical guide to the messy, painful, but ultimately possible art of rebirth, offering a playbook for resilience and rebuilding.

Introduction: When the Music Stops, But You Still Have to Dance

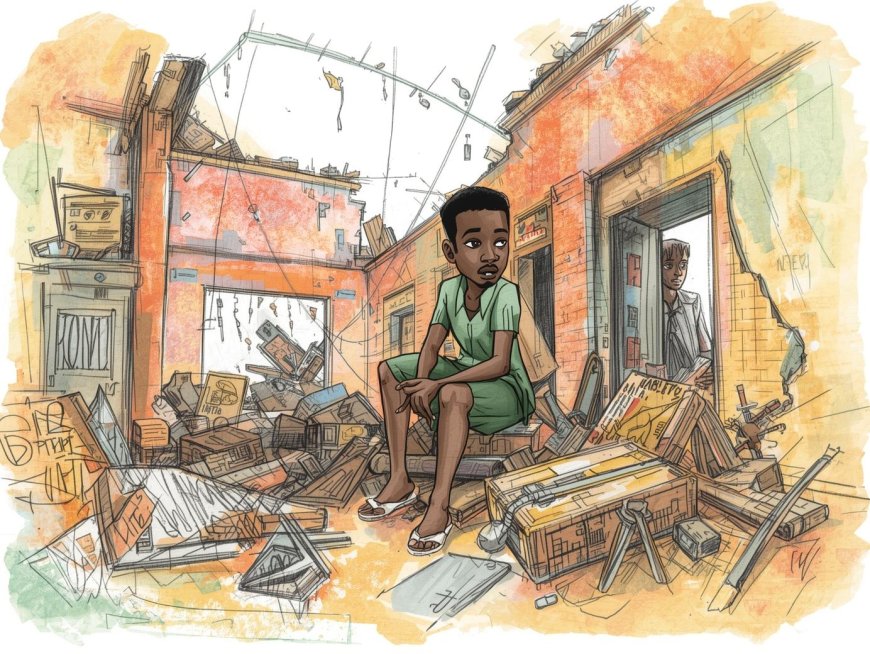

There is an African proverb that promises, “No rain that rains forever”.1 It is a simple, elegant assurance of resilience, a reminder that the fiercest storms eventually yield to clear skies. But when the storm is the collapse of a business you have built from nothing—a venture that has consumed your years, your health, your relationships—that promise can feel like a distant, cruel whisper. When a business fails, it does not just fail. It dies. And if you are its founder, you are not merely an attendee at the funeral; you are the chief mourner, the eulogist, and, in the eyes of many, the corpse.

This is a report about that funeral. It is an acknowledgment of the profound, often silent, grief that accompanies entrepreneurial failure on the African continent. It is a space to talk about the unspeakable: the shame, the fear, the disappointment, and the crushing weight of public expectation.2 Globally, the statistics are stark and oddly comforting in their universality. Ninety percent of startups will fail.3 Two out of three businesses will not survive.3 The lean startup movement even advocates for failing “fast and often” as a method of learning.4 These numbers are meant to normalize failure, to strip it of its sting and reframe it as a data point on the long road to success.

Yet, for an African entrepreneur, this is anything but a normal statistic. The global tech ecosystem may whisper that failure is a rite of passage, but the local community often screams that it is a personal disgrace. This creates a jarring dissonance. The founder is intellectually aware that most ventures fail, but they live in a cultural reality where that failure is personalized and catastrophized. In South Africa, the failure of an individual can bring shame to the entire group, a heavy burden in a collectivist society.5 In Ghana, it can lead to a devastating social exclusion known as ‘de-kinning,’ where family networks withdraw their support precisely when it is needed most.6 In Nigeria, where the pressure to project success is immense, failure is often seen not as an iteration but as a sign of incompetence and weakness, prompting founders to simply disappear into a digital graveyard of 404 errors and silent social media accounts.7

So, the African founder is caught between two worlds. One is the globalized, venture-backed world that preaches resilience and learning from mistakes.2 The other is the deeply-rooted, high-context world of community, kinship, and social reputation, where the stakes are infinitely higher than a balance sheet. This report navigates that treacherous space. It is an autopsy of business death, a cultural exploration of its ghosts, and a practical guide to the messy, painful, but ultimately possible art of rebirth. We will journey through the psychological wreckage, dissect the cultural pressures in Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, and Kenya, and examine the stark realities of failure and resilience in the continent’s burgeoning healthcare and HealthTech sectors. Because the rain does fall, and it is often a deluge. But the proverb holds true. It cannot rain forever. This is the story of what comes after the storm.

Part I: The Anatomy of a Business Death

Chapter 1: The Founder's Autopsy - More Than Just Bad Numbers

Before the public announcement, before the final payroll is missed, and long before the website goes dark, the death of a business begins as an internal collapse. It is a quiet, private unraveling within the founder's mind. To treat this purely as a financial event—a matter of burn rates and market fit—is to miss the profound human tragedy at its core. Business failure is a psychological shock, a deep trauma that reverberates through every aspect of an entrepreneur's life, often leading to long-term mental and physical health issues.9 It is an autopsy of the soul.

The experience is fundamentally one of grief. Research on post-failure entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa identifies a distinct process of recovery that mirrors the stages of mourning a loved one.10 This journey, as outlined by scholars, typically moves through four phases: grief and despair, transition, formation, and finally, a legacy phase where lessons are integrated.10 The initial phase is the most acute. It is characterized by a "devaluation of self-worth, doubt in their abilities, uncertainty about future career prospects, and negative emotions like guilt and shame".9 The founder is not just a person whose business failed; they feel like a failure as a person. Confidence and courage evaporate, replaced by a persistent sense of helplessness and hopelessness.9

This is because the business was never just a business. For most founders, it is a tangible extension of their identity, a manifestation of their dreams, intellect, and ambition. Its death is therefore experienced as the death of a part of oneself. The logo was their face; the brand was their reputation. When it disappears, it leaves a void that is both professional and deeply personal. This loss of identity is one of the most painful and disorienting aspects of the experience.

Compounding this grief is a unique and isolating form of guilt. Unlike the death of a loved one, where the bereaved is a victim of circumstance, the founder is often the one who has to make the final, fatal decision. They are the one who "pulls the plug," who signs the dissolution papers, who informs the team that the dream is over. This positions them as both the chief mourner and the executioner, a psychologically torturous role that can trap them in an endless loop of "what-ifs" and self-recrimination. Society has no rituals for this kind of death. There are no funerals for a limited liability company, no community-sanctioned mourning periods for a shuttered startup. While friends and family may gather to support someone who has lost a relative, they often fall silent or keep a respectful distance from someone who has lost a business. This silence, born of awkwardness or a fear of saying the wrong thing, leaves the founder to grieve alone.

This isolation is precisely what short-circuits the learning process that is meant to be the silver lining of failure. The entrepreneurial ecosystem is fond of the mantra "learn from your failures".8 However, genuine learning—the kind that leads to the "phoenix effect" of rising from the ashes to build something stronger—cannot begin until the grief has been processed.2 An ecosystem that stigmatizes the fall and provides no space for mourning is, in effect, preventing its entrepreneurs from absorbing the very lessons that could fuel future success. The founder, trapped in an unresolved cycle of grief and guilt, is unable to perform a clear-eyed autopsy on what went wrong. The emotional trauma obscures the strategic missteps, making it impossible to distinguish between market realities and personal failings. Before one can learn, one must first be allowed to grieve.

Chapter 2: The Public Hanging - When Your Failure is a Spectator Sport

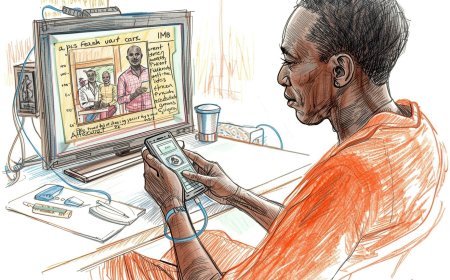

The private agony of a business's death is made exponentially worse when it unfolds under the public gaze. In the modern entrepreneurial landscape, particularly in the hyper-connected tech sector, founders are encouraged to "build in public." They share their wins, announce funding rounds with celebratory posts, and cultivate a brand persona to attract talent, customers, and investors. This visibility is the engine of growth. But when the engine seizes, that same visibility becomes an instrument of public humiliation. The failure becomes a spectator sport, and the founder is the main event.

The user’s query captured this horror perfectly: "people don’t just see a business that failed — they see you as the failure. They think you died." This is the brutal reality of the weaponization of visibility. The digital tools essential for building a brand—social media, the tech press, industry forums—do not disappear when the business does. The triumphant articles announcing a seed round remain online, forever searchable, standing in stark, mocking contrast to the eventual silence. This digital ghost haunts the founder, a permanent record of a dream that died.

This experience is particularly acute in Africa's high-context, collectivist cultures, where social esteem and reputation are invaluable currencies.5 In Nigeria's tech scene, for instance, there is an unspoken rule known as the "Always Up" delusion.7 Founders are expected to project an aura of relentless progress and unshakeable confidence. Every public communication is curated to signal growth, from celebrating vanity metrics to announcing partnerships. Admitting struggle is taboo; it is perceived as weakness or incompetence. The result is an ecosystem where "dead startups don't talk".7 When a company fails, the founders often simply vanish. Their social media goes dormant, their websites return a 404 error, and the vibrant public persona is replaced by an eerie silence. This disappearance is not just about personal shame; it is a strategic retreat from a community that has little vocabulary for failure beyond judgment.

The pressure to maintain this facade is immense, and the fear of public judgment is a powerful silencer. This fear is not just about personal reputation. For many African entrepreneurs, there is a deeper, more painful burden: the fear of letting down their community, or even their continent. Ghanaian entrepreneurs, for example, worry that speaking openly about their failures might "bring (more) shame to themselves and their kin or feed into racial stereotypes about Ghana and Africa as 'lacking'".6 This is a staggering weight to carry—the feeling that your individual business failure reinforces a negative narrative about your entire people. It transforms a personal setback into a perceived collective failing.

Thus, the celebrated Silicon Valley ethos of "building in public" becomes a high-risk, high-reward gamble in an African context. The very visibility required to secure funding and market share is the same visibility that ensures the failure will be public, painful, and socially consequential. It creates a powerful disincentive for transparency and vulnerability, the very qualities needed to foster a mature ecosystem where failure can be openly discussed and learned from. Instead of a shared learning experience, each failure becomes a private, isolating trauma, played out on a public stage for an audience that is often quick to judge and slow to forget.

Part II: The Ghost in the Machine - Cultural Autopsies of Failure Across Africa

Chapter 3: Nigeria - The Hustle, The Hype, and The Heavy Heart

Lagos. The very name conjures images of vibrant chaos, of relentless energy, of a hustle that never sleeps. It is the undisputed hub of African tech, a city where dreams are scaled on pitch decks and fortunes are sought in the frenetic dance of venture capital. But beneath the hype, behind the headlines celebrating multi-million dollar rounds, lies a brutal reality. In Nigeria, an estimated 80% of small and medium enterprises die within their first five years.12 This is not merely a consequence of market forces; it is deeply entangled with the country's unique socio-cultural fabric. Factors such as endemic corruption, norms around ownership, religious beliefs, and, most visibly, an "ostentatious life style" are cited as direct contributors to business failure.12

To understand failure in Nigeria, one must first understand the performance of success. Consider the satirical but all-too-real tale of Tunde the Tech Bro. Tunde, armed with a brilliant idea and a slick presentation, secures a $500,000 pre-seed round. The first thing he does is not to double down on product development, but to upgrade his life. He moves from his modest mainland apartment to a swanky new place in Lekki Phase 1. He trades his reliable Toyota for a newer, more impressive SUV. He is a regular at the city's trendiest spots, his social media a curated feed of success. Tunde is not necessarily reckless or malicious; he is playing a role demanded by the ecosystem. In Lagos, you must look like a winner to be treated like one. This performance, this "ostentatious life style," becomes a significant and unspoken line item in the company's burn rate. The pressure to "look the part" is immense, fueled by a culture that often conflates appearance with substance.

This performance culture creates what has been termed the "Always Up" delusion.7 Every founder is "redefining finance" or "empowering Africa's next billion." No one is talking about their dwindling runway, the co-founder disputes, or the fact that investors have stopped taking their calls. This enforced optimism makes the eventual, inevitable failures all the more jarring and shameful. When the money runs out and the performance can no longer be sustained, the response is not an open post-mortem but a sudden, deafening silence. As one analysis puts it, "When they fail, silence... founders disappear without a word. All we see is just a vanished website and a 404 error".7

This silence is a defense mechanism in an environment that views failure not as a learning opportunity, but as a definitive judgment on a founder's competence and character.7 The stories of what truly went wrong—the market miscalculations, the co-founder conflicts, the crippling effects of a devaluing Naira on dollar-denominated server costs—are buried along with the company.13 This buries the data, preventing the ecosystem from learning collectively. The great titans of Nigerian industry, like Aliko Dangote, preach that "tenacity of purpose is supreme".14 But the ghosts of Nigeria's startup graveyard whisper a different truth: tenacity alone cannot save you when your business model is flawed, your burn rate is unsustainable, and your market is not ready for what you are selling. The hustle is real, but so is the heartbreak.

Chapter 4: Ghana - When Your Family Unfriends You: The Agony of 'De-kinning'

In many Western cultures, the ultimate safety net is the state or individual savings. In Ghana, as in much of Africa, the primary social safety net has always been kinship. The family is the first investor, the loudest cheerleader, and the final refuge. It is a system built on reciprocal obligations and collective well-being. But what happens when a central pillar of that system—the expectation of upward mobility—is shattered by a failed business? In Ghana, the consequence can be a unique and devastating form of social death known as "de-kinning".6

'De-kinning' is the slow, painful process of being excluded from the family's network of care and support.6 It is a social unfriending by the people who are supposed to be your last line of defense. This is not about a simple loss of face; it is about the failure to fulfill deep-seated cultural duties. For young Akan entrepreneurs, these expectations are clear. After university, they are given a "window of opportunity" to establish a middle-class career, often with the family's pooled resources.6 The expectation is that the investment will be returned, not just financially, but through fulfilling specific kinship roles. A successful son is expected to fund his younger siblings' education. He is expected to accumulate enough resources to pay a bride price and enter into a middle-class Christian marriage, thereby securing the family's status and continuity.6

When a startup fails, it is not just a personal financial loss; it is a default on this sacred social contract. The story of Kwabena Osei, a young Ghanaian entrepreneur, is a poignant illustration. After his startup collapsed, he felt he had failed to "return investment" to his family. The result was catastrophic: his family "ceased all contact with him in shame and disappointment," and he felt he could no longer rely on their care.6 He was, in essence, de-kinned. He was cast out precisely at the moment of his greatest need.

This intense pressure is compounded by a pervasive fear of financial inadequacy that haunts many aspiring Ghanaian entrepreneurs.15 The historical challenges for small businesses, coupled with bureaucratic hurdles and high interest rates, create an environment where the risk of failure is terrifyingly high.15 The failure is not just about losing money; it is about losing one's place in the most important social unit of all. It is the fear of being unable to afford marriage, of being unable to support one's siblings, of becoming a liability rather than an asset to the family name.

There is a powerful Ghanaian proverb that says, "The one who climbs a good tree gets a push".16 It speaks to the community's willingness to support a worthy endeavor. The tragic irony for many failed entrepreneurs is the unspoken corollary: when your tree falls, the community may not rush to help you replant. They may simply walk away from the wreckage, leaving you alone in the clearing, stripped not only of your business but of your belonging.

Chapter 5: South Africa - The Weight of 'Ubuntu': When Your Failure Shames the Village

'Ubuntu'—"I am because you are"—is one of South Africa's most profound philosophical gifts to the world. It is a concept of interconnectedness, of communal strength, of the idea that an individual's well-being is inextricably linked to the well-being of the group.5 It is the bedrock of a society that values the collective over the individual. In the context of building a community or a nation, it is a powerful, unifying force. But in the high-stakes, individualistic world of entrepreneurship, 'ubuntu' can manifest as a crushing weight.

The entrepreneurial journey, by its very nature, demands a degree of individualism—a willingness to take risks, challenge norms, and stand apart from the crowd. This is often in direct tension with a collectivist culture that prioritizes conformity and group identity.5 In South Africa, this tension comes to a head at the moment of failure. Because of the principle of 'ubuntu', a business failure is rarely seen as just an individual's misfortune. Instead, "the failure of an individual brings shame to the entire group".5 The entrepreneur has not just lost their own investment; they have, in a sense, tarnished the community's reputation. This transforms a private financial loss into a public social failing, stifling the very risk-taking that entrepreneurship requires.

This cultural pressure is then brutally reinforced by a systemic and institutional framework that actively penalizes failure. Unlike the American system, where Chapter 11 bankruptcy can offer a clean slate and a chance to start again, the South African system is far less forgiving. An entrepreneur whose business fails faces tangible, long-lasting consequences. They are likely to be blacklisted, making it nearly impossible to secure credit in the future. Approaching a bank for a second loan becomes an exercise in futility. Debt agreements can lead to being banned from obtaining further credit altogether.5 This creates what analysts call an "inappropriate risk-reward ratio".5 The potential rewards of success are weighed against the catastrophic and enduring penalties of failure, and for many, the risk is simply too great.

The statistics bear this out. South Africa suffers from a disturbingly high failure rate for small, micro, and medium enterprises (SMMEs), with over 70% folding within their first five to seven years.20 While these businesses are touted as the solution to the country's staggering unemployment, their high mortality rate means they cannot generate the economic growth or jobs required.20 This is not just an economic problem; it is a crisis of mindset and structure. The very philosophy of 'ubuntu' that should provide a supportive network can, in the context of failure, become a source of immense social pressure. When this is combined with a financial system that offers no second chances, the result is an environment that is profoundly hostile to the trial-and-error nature of innovation. The proverb "A person is a person because of other people" 19 is a beautiful ideal, but for the failed entrepreneur, it can feel like a verdict delivered by a jury of their peers.

Chapter 6: Kenya - The Land of "Inauma but Inabidi Uzoee" (It Hurts, but You Have to Get Used to It)

If there is a phrase that encapsulates the Kenyan approach to the relentless challenges of entrepreneurship, it is the Sheng (Nairobi slang) expression, "Inauma but inabidi uzoee".23 It translates to, "It hurts, but you have to get used to it." This is not a statement of defeat, but one of profound, pragmatic, and often darkly humorous resilience. It is the verbal shrug of a people who navigate a daily obstacle course of systemic failures with a characteristic blend of grit, ingenuity, and wit.

The list of obstacles is long and well-documented. Kenyan startups grapple with limited access to capital, where high interest rates and risk-averse investors create a significant funding gap.24 They struggle with inadequate market research and a failure to validate demand before launch.24 They are ensnared in complex and often ambiguous regulatory and legal frameworks, where bureaucracy can stall progress for months.24 They are hampered by infrastructure gaps, from unreliable internet to inconsistent power, and face a constant battle to attract and retain skilled talent in a competitive market.24 It is a tough, unforgiving environment.

Yet, paradoxically, the Kenyan culture demonstrates a remarkable tolerance for uncertainty.26 An analysis of the national mood leading up to a contentious election showed that, unlike in many other parts of the world where such uncertainty would grind the economy to a halt, Kenyan consumers and businesses continued to operate with relative robustness.26 This speaks to a deep-seated cultural resilience, an ingrained ability to adapt and persevere in the face of instability. This is the spirit of "inabidi uzoee."

This attitude is reflected in the country's rich tapestry of witty sayings and entrepreneurial wisdom. The late, legendary industrialist Chris Kirubi's advice is a classic: "Many people either have results or reasons; decide today the kind of person you want to be – one who delivers results or always has reasons for not having results".27 It is a call to action, a rejection of victimhood. The Swahili proverbs found on traditional kanga cloths offer similar pearls of wisdom, like the hilariously practical, "Heri pancha ya pajaro kuliko rafiki mwenye kero"—"It is better to have a flat tyre on your Pajero than have a troublesome friend," a lesson easily applied to vetting co-founders and partners.28 The country's comedians frequently mine the entrepreneurial hustle for material, turning the daily struggles of business into shared moments of laughter and recognition, a testament to the national ability to find humor in hardship.29

However, this celebrated resilience may be a double-edged sword. While it is an indispensable survival tool for the individual entrepreneur, it may inadvertently perpetuate the very systemic problems they face. The culture of finding individual workarounds and "getting used to" the broken parts of the system can diffuse the collective pressure needed to demand fundamental change. If everyone is focused on navigating the obstacle course, who is demanding that the course be rebuilt? The very trait that allows Kenyan entrepreneurs to survive the harsh environment day-to-day might be what prevents the environment itself from becoming less harsh over the long term. It hurts, and they get used to it. But perhaps the next stage of the ecosystem's evolution will be to collectively decide that they no longer have to.

Part III: The Morgue and The Maternity Ward - Case Studies from African HealthTech

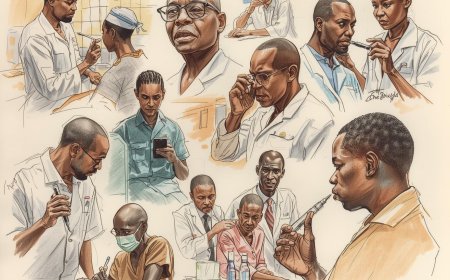

Chapter 7: Post-Mortem Report: The Ghost of 54Gene

In the world of African tech, few stories are as epic, or as tragic, as that of 54Gene. It was a venture born of a grand and noble vision, one that promised to correct a historic injustice at the very heart of modern medicine. Its death was not a quiet fizzle but a spectacular collapse that sent shockwaves through the continent's biotech and venture capital ecosystems. To understand its failure is to perform an autopsy on a dream, one that reveals complex pathologies of ambition, governance, and the brutal realities of building a deep-tech company in Africa.

The vision belonged to Dr. Abasi Ene-Obong. As a medical student in Nigeria, he was struck by a staggering fact: less than 3% of the genetic data used in global pharmaceutical research came from Africans.32 This data gap meant that the drugs and therapies of the future were being developed without Africa in mind, perpetuating a cycle of health inequity. Ene-Obong abandoned his path to becoming a doctor and dedicated himself to genetics and bioscience, eventually launching 54Gene in 2019—named for the 54 countries in Africa—with a singular, powerful mission: "to unlock the African genome and make Africa a significant contributor to global health research".32

The company's rise was meteoric. It attracted significant international investment and quickly became a beacon of African innovation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 54Gene stepped into a critical public health role, becoming a pivotal part of Nigeria's testing and sequencing response.33 It was a moment of validation, a demonstration of the immense potential of local scientific expertise.

But behind the scenes, the pressures were mounting. For the first time publicly, Dr. Ene-Obong has spoken of a "hostile takeover that blindsided him and eventually led to the collapse of the very company he built from the ground up".33 While the specific details of the internal power struggles remain complex, the outcome was clear. The founder, the visionary, was pushed out. The company, stripped of its original leadership and struggling to find a sustainable financial path, ultimately shut down, unable to "continue to operate financially".35

The failure of 54Gene was not a simple case of a bad idea or a lack of market. The market need is undeniable. Instead, its collapse points to more complex issues. It highlights the immense challenge of building a capital-intensive, long-term scientific enterprise in a venture ecosystem that often prioritizes rapid, asset-light growth. It underscores the critical importance of robust corporate governance and founder alignment with investors, especially when the stakes are so high. The way the shutdown was handled drew criticism, with some analysts arguing that it was a "systemic failure rather than a natural consequence of experimentation," particularly given the millions in capital that were burned through.36 Dr. Ene-Obong's story is a cautionary tale about how a world-changing vision can be derailed by the terrestrial forces of boardroom politics and financial unsustainability. He has since founded a new venture, Syndicate Bio, to continue the mission.33 The ghost of 54Gene serves as a stark reminder that in the quest to solve Africa's biggest problems, having a brilliant idea is only the beginning of the battle.

|

Date/Year |

Event |

Capital Raised |

Key Narrative Point |

|

2019 |

Company founded by Dr. Abasi Ene-Obong |

Seed: $4.5M |

Vision articulated: to address the 3% African representation in genomic data.32 |

|

2020 |

Series A funding round |

$15M |

Company gains traction and international recognition for its mission.37 |

|

2020-2021 |

COVID-19 Pandemic Response |

N/A |

54Gene becomes a key player in Nigeria's testing and sequencing efforts, showcasing its capabilities.33 |

|

2021 |

Series B funding round |

$25M |

Peak of investment and public profile; expansion and new labs announced.35 |

|

Oct 2022 |

Founder Dr. Ene-Obong steps down as CEO |

N/A |

Reports of internal power struggles and a shift in leadership emerge.33 |

|

2023 |

Company struggles and downsizes |

N/A |

The company faces financial difficulties, leading to significant operational cutbacks.35 |

|

Sep 2023 |

54Gene announces shutdown |

N/A |

The company ceases operations, citing its inability to "continue to operate financially".35 |

|

Post-2023 |

Founder launches Syndicate Bio |

N/A |

Dr. Ene-Obong begins a new venture to continue the original mission, carrying forward the lessons learned.33 |

Chapter 8: The Patient is Bleeding Out: When Systems Fail Startups

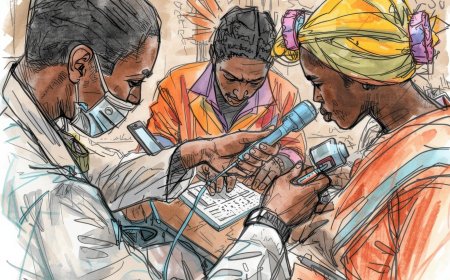

Sometimes, a startup's death certificate should list "complications from a toxic environment" as the cause of death. A brilliant product, a dedicated team, and a clear market need can all be rendered irrelevant when the ecosystem itself is fundamentally unhealthy. In the African HealthTech space, founders must contend not only with the standard challenges of building a business but also with the unpredictable and often arbitrary actions of state actors and the volatile whims of international capital. This external fragility, which can be called the "sovereignty risk of innovation," can be just as fatal as any internal misstep. Two cases, from Ghana and Kenya, illustrate this stark reality.

In Ghana, the case of Lightwave Health Information Management System (LHIMS) is a tragic story of a startup being starved to death by its most important partner: the government. For nearly a decade, LHIMS has been the "digital backbone" of Ghana's healthcare system, a locally built platform that digitized over 26 million patient records and connected hospitals across the country.38 Yet, this critical piece of national infrastructure is now on the brink of collapse. Why? According to reports, the Ministry of Health simply stopped paying. The company's contract expired in late 2024, and despite continuing to run the entire system—providing 24/7 technical support, maintaining servers, and even replacing fire-damaged hardware at its own expense—Lightwave allegedly has not received a single cedi from the Ministry for over nine months.38 Insiders are clear: this is a "governance failure, not a technical one".38 The potential consequence is not just the failure of one company, but the erasure of a decade of e-health progress for an entire nation, forcing hospitals back to paper records and jeopardizing patient care.38 The LHIMS crisis shows how a startup's survival can be entirely dependent on the whims of bureaucratic and political actors, a risk that is impossible to mitigate through a better product or a smarter business model.

In Kenya, Ilara Health faced a different kind of external shock, one that highlights the precariousness of relying on international funding. Ilara Health, founded in 2019, built a successful model providing affordable diagnostic devices and software to thousands of primary care clinics across Kenya, reaching millions of patients.39 The company was making steady progress, securing a $4.2 million funding round in early 2024 and a $1 million loan from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) in early 2025.39 Yet, by September 2025, the company was forced to announce significant layoffs and a major restructuring. The stated reason was a sudden and unexpected "reversal of funding commitments and delays in disbursements".39 Even with a proven model and a clear social impact, Ilara Health was crippled when the promised capital failed to materialize.

These two stories reveal a deeper truth about entrepreneurship in Africa. Founders are not just building companies; they are navigating deeply unpredictable political and geopolitical landscapes. The risk of a government partner defaulting on a contract or a foreign venture fund suddenly changing its strategy is real and ever-present. This forces founders to build for extreme fragility, to maintain contingency plans for scenarios that are entirely outside of their control. It reframes many so-called "startup failures" not as failures of entrepreneurship, but as casualties of a high-risk environment where the rules of the game can change without warning.

Chapter 9: The Phoenix Protocol - Stories of Rebirth and Pivots

Out of the ashes of a failed venture, a stronger, wiser entrepreneur can emerge. This "phoenix effect" is not a myth; it is a documented phenomenon where the painful lessons of failure become the foundational blueprint for future success.2 The African startup landscape is filled with these stories of rebirth—founders who weathered the storm of collapse and returned to build more resilient, focused, and ultimately more successful businesses. Their journeys offer the most potent form of hope: the proof that an ending is often just a prelude to a new beginning.

William McCarren's story is a masterclass in learning and adapting. His first major venture, Zumi, a Kenya-based startup, endured a painful journey of over-experimentation. It began as a women-focused digital magazine, struggled with low ad revenue, pivoted unsuccessfully to B2B e-commerce, and finally shut down permanently in 2023 after burning through its funding and laying off 150 employees.42 It was a public and difficult failure. But McCarren did not disappear. He relocated to South Africa, a larger e-commerce market, and launched a new venture: FARO, a recommerce startup focused on making fashion affordable by transforming surplus and returned items.42 The difference was focus. Where Zumi had been scattered, FARO was "laser-focused" on a single, clear business model with strong unit economics. The result? Within a year, FARO achieved $2.3 million in revenue and secured $6 million in funding—a stunning rebound built directly on the harsh lessons of Zumi's collapse.42

Perhaps one of Nigeria's most influential tech figures, Iyinoluwa Aboyeji, co-founder of two billion-dollar companies, Andela and Flutterwave, speaks openly about the role of failure in his journey. He admits that his earliest angel investments taught him humility because "we lost money".43 His decision to leave Andela, a company he co-founded, to start Flutterwave was seen by many as "irrational on paper".43 It was a leap of faith, a pivot driven by a deep conviction that there was another, bigger problem to solve in Africa's fragmented payments landscape.44 That conviction, born from the experience and scars of his previous ventures, led to the creation of one of the continent's most valuable startups.

This spirit of turning adversity into innovation is particularly vibrant in the HealthTech sector, where founders often draw motivation from deeply personal experiences. In Nigeria, Virtue Oboro was inspired to create Crib A'Glow after her own newborn son suffered from severe jaundice and could not get timely treatment due to a lack of equipment.45 Her response was to invent a portable, solar-powered phototherapy crib designed specifically for rural and suburban communities with unstable electricity. She turned a moment of personal terror into a life-saving innovation. Similarly, in South Africa, Thato Schermer founded Zoie Health, a digital health platform for women, based on her own lived experience of a healthcare system that she felt was "expensive, fragmented, and impersonal".46 Her mission is to turn "pain into product," building a system rooted in the empathy and community support that she found lacking. These founders did not need to fail in business first; they transformed life's failures and frustrations into their founding mission, building companies that are resilient by design because they are forged in the fire of real, lived problems.

Part IV: The Art of the Second Act - A Practical Guide to Rebuilding

Chapter 10: From Grief to Grit - Hacking Your Psychology

The journey back from the brink of entrepreneurial failure is, first and foremost, a psychological one. Before a new business plan can be drafted or a new pitch deck designed, the founder must undertake the difficult work of rebuilding their own internal world. The grief, shame, and self-doubt detailed in the first part of this report are not weaknesses to be ignored, but wounds that require healing. Moving from grief to grit requires a conscious and proactive approach to mental and emotional recovery.

The principles of positive psychology offer a powerful framework for this process. The goal is to cultivate internal qualities like "resilience, optimism, and a quest for meaning," which can significantly enhance an entrepreneur's ability to withstand stress and bounce back from adversity.9 This is not about toxic positivity or pretending the pain doesn't exist. It is about actively re-evaluating the failure experience, not as a final verdict on one's worth, but as a source of valuable, albeit painful, data.2 The first step is to reframe the narrative. Instead of "I am a failure," the thought becomes "My business failed, and this is what I learned." This subtle but crucial shift separates the founder's identity from the venture's outcome, creating the psychological space needed for recovery and growth.

A critical component of this recovery is breaking the cycle of isolation. The instinct after a public failure is often to retreat, to hide from the perceived judgment of the world. This is the most dangerous thing a founder can do. Building resilience requires actively seeking out and leaning on support networks.2 This means reaching out to trusted mentors, connecting with other founders who have walked a similar path, and being vulnerable with investors who have a long-term perspective. These are the people who understand the journey and can offer not just sympathy, but strategic advice and a reminder that failure is not a fatal condition. As Dare Olarewaju, founder of Oxratech, argues, embracing this vulnerability is a sign of strength, cutting against the traditional view in many African work environments that one must always project an image of invincibility.2

Finally, it is essential to destigmatize the need for professional mental health support. The psychological toll of failure can be immense, leading to anxiety, depression, and burnout.2 Organizations like StrongMinds, which provides free, community-based group therapy in countries like Uganda and Zambia, are doing vital work to make mental healthcare accessible on the continent.47 Seeking therapy is not an admission of defeat; it is an act of strategic self-preservation. Just as an athlete needs a physical therapist to recover from an injury, an entrepreneur needs mental and emotional support to recover from the trauma of a business collapse. Hacking your psychology is about assembling a toolkit for resilience: reframing the narrative, building a strong support system, and seeking professional help when needed. It is the foundational work upon which any second act must be built.

Chapter 11: The Resilient Founder's Playbook

After the psychological rebuilding comes the strategic reboot. The lessons learned from the morgue of failed startups—both one's own and others'—must be synthesized into a new playbook for building a more durable, adaptable, and context-aware business. The post-2023 funding winter and the high-profile collapses across the continent have fundamentally shifted the definition of a "good" startup in Africa. The era of celebrating "growth at all costs" is over.48 The new ideal is not the mythical unicorn, but the resilient "cockroach"—a business built to survive anything the harsh environment can throw at it. This playbook is for building cockroaches.

Lesson 1: Context is King. The single greatest mistake a founder can make is to build for a theoretical market instead of the one that actually exists. This means designing for Nigerian realities: erratic power, high infrastructure costs, low consumer purchasing power, and extreme regulatory volatility.13 A successful business model must be stress-tested against the "Lagos stress test": Can your app work on a 2G connection? Can your pricing be sustained by someone earning a civil servant's salary? Does your logistics plan account for apocalyptic traffic? [Planetweb.ng insight]. As Iyinoluwa Aboyeji notes, African founders must tackle global problems but with "unusually creative and resilient solutions" forged by local constraints.43

Lesson 2: Cash Flow is Your Chi. There is an Igbo proverb: "When a man says yes, his chi (personal god) says yes also".49 In the world of business, your chi—your guiding spirit, your life force—is positive cash flow. Investors have fallen back to basics; they want to see the numbers, not just the story.48 Aboyeji puts it bluntly: "Profit is proof of life".43 Capital should be treated like "oxygen, not fireworks".43 The goal is to design a business that can reach break-even quickly and survive without the next funding round, using revenue as its primary fuel [Planetweb.ng insight].

Lesson 3: Failure is Data, Not a Disgrace. A resilient founder must actively fight against the cultural stigma of failure and cultivate a culture of experimentation within their organization. Every failed experiment, every flawed feature, every missed sales target is a piece of valuable data.2 The key is to "fail small, fast, and cheaply".2 This requires creating crisis management and contingency plans before they are needed and having transparent conversations with the team about what is not working.2 This approach turns failure from a source of shame into a strategic asset.

Lesson 4: Build a Company, Not a Cult of Personality. In an ecosystem that often elevates charismatic founders, it is tempting to build the entire brand around one individual. This is a fatal mistake. A truly resilient business must be able to survive the founder's departure, whether due to burnout, illness, or a new opportunity [Planetweb.ng insight]. This requires intentionally building strong systems, documenting processes, and empowering a deep bench of leadership talent. The founder should be the face of the company, not its entire foundation.

Lesson 5: Your Network is Your Net Worth. In the collectivist societies of Africa, community is a superpower. A founder's ability to build and leverage a strong network of mentors, peers, advisors, and even friendly competitors is a critical determinant of success. This network is the source of advice during moments of doubt, the first line of defense in a crisis, and the web of relationships that can unlock unforeseen opportunities.2 Proactively building these connections is not a distraction from the "real work" of building a product; it is an essential part of building a resilient enterprise.

Conclusion: Praising the Lizard After the Fall

In the vast and varied anthology of African wisdom, there is a Nigerian proverb that speaks directly to the lonely aftermath of a great fall. It says: "The lizard that jumped from the high Iroko tree to the ground said it would praise itself if no one else did".49

This is the final, most essential lesson for the African entrepreneur. After the business has died, after the public funeral and the private grief, after the de-kinning and the blacklisting, after the silence of friends and the judgment of strangers, you may find yourself alone in the clearing. The ecosystem, with its short memory and obsession with the next big thing, may not applaud your survival. Your family, hurt and disappointed, may not understand the scars you carry. The world will have moved on.

In that quiet moment, the proverb offers not just solace, but a command. You must praise yourself. You must be the one to acknowledge the audacity it took to climb the Iroko tree in the first place. You must be the one to recognize the immense courage it took to jump, to take the leap of faith that is entrepreneurship. You must be the one to honor the wisdom gained from the brutal, dizzying fall. And you must be the one to celebrate the sheer, stubborn resilience it takes to pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and walk away, not broken, but forged anew.

This report has been an autopsy, a cultural critique, and a guide. But its ultimate purpose is to serve as a witness. A witness to the silent grief, the public shame, and the arduous journey of rebuilding. It is a call to action for founders to reclaim their narratives, to tell the true, unvarnished stories of their failures, not as confessions of incompetence, but as chronicles of experience. And it is a challenge to the broader African ecosystem—to investors, to mentors, to the media, to all of us—to finally stop burying our dead. We must learn to see the ghosts of failed startups not as specters of shame, but as ancestors whose stories hold the lessons we need to build a more resilient, more empathetic, and more prosperous future. The scars of failure are not a mark of disgrace. They are the hard-won badges of honor, earned in the brutal, beautiful arena of African entrepreneurship. Praise the lizard.

Works cited

-

Facing TOUGH TIMES! No Rain That Rains For Ever! An African Proverb! - Medium, accessed October 29, 2025, https://medium.com/@josephchege222/facing-tough-times-no-rain-that-rains-for-ever-an-african-proverb-b46b0d72a004

-

Failing does not mean losing– lessons African founders can learn from failure, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.foundersfactory.africa/blog/lessons-african-founders-can-learn-from-failure

-

Business failure is stigmatised in Africa, we need to move away from that if we're going to grow. - YouTube, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1XC6V2zrWEk

-

Rethinking fear of failure GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.gemconsortium.org/news/rethinking-fear-of-failure

-

Too scared to fail: barriers to small business growth | Leader.co.za, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.leader.co.za/infocentrearticle.aspx?s=5&c=137&a=3135&p=2&title=Startups

-

Digital Start-Up Nightmares: Failure and Fractured Families in ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://africanarguments.org/2025/05/digital-start-up-nightmares-failure-and-fractured-families-in-ghana/

-

Dead Startups Don't Talk What Founders Won't Say About Nigeria's Tech Winter, accessed October 29, 2025, https://techeconomy.ng/dead-startups-dont-talk-what-founders-wont-say/

-

Influence of Knowledge and Failure Experience on Entrepreneurial Intentions in East African Businesses - RSIS International, accessed October 29, 2025, https://rsisinternational.org/journals/ijriss/Digital-Library/volume-8-issue-12/2370-2384.pdf

-

(PDF) Psychological Resilience of Entrepreneurial Failure: An ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376589145_Psychological_Resilience_of_Entrepreneurial_Failure_An_Application_of_Positive_Psychology_to_Entrepreneurial_Failure_Repair

-

Do entrepreneurs always benefit from business failure experience? - White Rose Research Online, accessed October 29, 2025, https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/127679/3/JBR%20Accepted%20-%20Final.pdf

-

How do Entrepreneurs Experience Business Failure (Rawal and Sarpong)_Revised v3_FINAL.pdf, accessed October 29, 2025, https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/34478/1/How%20do%20Entrepreneurs%20Experience%20Business%20Failure%20%28Rawal%20and%20Sarpong%29_Revised%20v3_FINAL.pdf

-

SMALL AND MEDIUM SCALE BUSINESS ... - IJRDO Journal, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.ijrdo.org/index.php/sshr/article/download/2035/1790/

-

Failed Nigerian Startups: Lessons, Mistakes & What to Avoid ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://planetweb.ng/failed-nigerian-startups/

-

20 Inspirational Quotes From Entrepreneurs In Africa - Piggyvest Blog, accessed October 29, 2025, https://blog.piggyvest.com/money-tips/quotes-from-entrepreneurs/

-

Finance and Fear: The Unseen Barriers to Ghana's Entrepreneurial Growth, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.modernghana.com/news/1329896/finance-and-fear-the-unseen-barriers-to-ghanas.html

-

10 Powerful Ghanaian Proverbs About Life: Timeless Wisdom for Inspiration, accessed October 29, 2025, https://lifeinspiration4all.com/2024/10/05/amazing-inspirational-ghanaian-proverbs-about-life/

-

The 50 Most Important Akan Proverbs - Adinkra Symbols & Meanings, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.adinkrasymbols.org/pages/the-50-most-important-akan-proverbs/

-

Powerful Ashanti Proverbs About Life, Wisdom, and Culture to Share Across Generations | Explore Kumasi, accessed October 29, 2025, https://explorekumasi.com/ashanti-proverbs-wisdom-culture/

-

African proverbs to celebrate Black History Month | YouAlberta, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.ualberta.ca/en/youalberta/2024/02/african-proverbs-to-celebrate-black-history-month.html

-

The causes and impact of business failure among small to micro and medium enterprises in South Africa, accessed October 29, 2025, https://apsdpr.org/index.php/apsdpr/article/view/210/365

-

The causes and impact of business failure among small to micro and medium enterprises in South Africa, accessed October 29, 2025, https://apsdpr.org/index.php/apsdpr/article/view/210/364

-

The Factors influencing SME Failure in South Africa - University of Cape Town, accessed October 29, 2025, https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/25334/thesis_com_2017_leboea_sekhametsi_tshepo.pdf

-

What are your favorite quotes/phrases in Kenya? - Reddit, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Kenya/comments/195jo0r/what_are_your_favorite_quotesphrases_in_kenya/

-

Exploring the 7 Challenges Faced by Kenyan Startups | by Rensyl Integral | Medium, accessed October 29, 2025, https://medium.com/@rensylintegral/decoding-startup-failure-exploring-the-7-challenges-faced-by-kenyan-startups-1cd3b71d4dee

-

The Top Reasons Why Businesses Are Failing in Kenya and How to Avoid Them, accessed October 29, 2025, https://stratexalign.com/the-top-reasons-why-businesses-are-failing-in-kenya-and-how-to-avoid-them/

-

How cultural differences affect business operations, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/lifestyle/society/how-cultural-differences-affect-business-operations-2129018

-

Business Quotes - Biashara Leo Digital, accessed October 29, 2025, https://biasharaleo.co.ke/business-quotes/

-

Learn Swahili: 21 Inspirational Kanga Sayings - Google Arts & Culture, accessed October 29, 2025, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/learn-swahili-21-inspirational-kanga-sayings-national-museums-of-kenya/9gVBlAZer2a1Lw?hl=en

-

Eugene Mbugua on Money, Media & Making It Big - YouTube, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h_ShdwFlWYo

-

070 - THE BUSINESS OF BEING FUNNY - EOTWE (FT BASHIR HALAIKI) - YouTube, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gvdoy-KizpA

-

3 Lessons For Small Business Owners From Stand-Up Comedy - Kuza Biashara, accessed October 29, 2025, http://www.kuzabiashara.co.ke/blog/comedy/

-

54gene's CEO Wants to Fix Health Data's Racial Imbalance | TIME, accessed October 29, 2025, https://time.com/6204230/54gene-racial-imbalance-genetic-data/

-

The untold story about 54gene | A chat with Dr Abasi Ene-Obong ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGaSVynzBtg

-

Increasing sequencing and analysis capabilities in Africa and enhancing COVID-19 testing in Nigeria - BioTechniques, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.biotechniques.com/whole-genome-studies/abasi-ene-obong-bringing-sequencing-and-analysis-to-africa-and-enhancing-covid-19-testing-in-nigeria/

-

15 African tech startups that shut down in 2023: Why they did it ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://afridigest.com/15-african-tech-startups-shut-2023/

-

More Nigerian startups shut down amid supportive policies, accessed October 29, 2025, https://punchng.com/more-nigerian-startups-shut-down-amid-supportive-policies/

-

Dr Abasi Ene - Obong, CEO of 54 Gene - YouTube, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gUoG43ygnPo

-

Ghana's Digital Health Backbone Collapsing Over Ministry ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://thechronicle.com.gh/ghanas-digital-health-backbone-collapsing-over-ministry-negligence/

-

Kenya's Ilara Health cuts staff as funding crunch forces restructuring, accessed October 29, 2025, https://techcabal.com/2025/09/25/kenyas-ilara-health-cuts-staff-in-restructuring/

-

Kenyan Healthtech Ilara Health Announces Significant Layoffs - TechTrendsKE, accessed October 29, 2025, https://techtrendske.co.ke/2025/09/25/ilara-health-layoffs/

-

Ilara Health lays off staff amid restructuring in Kenya - Techpoint Africa, accessed October 29, 2025, https://techpoint.africa/insight/techpoint-digest-1189/

-

Five Times African Founders Rebounded from Startup Failures ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://launchbaseafrica.com/2025/01/17/five-times-african-founders-rebounded-from-startup-failures-and-what-they-did-differently/

-

Build for the 94%: Nigeria's Iyinoluwa Aboyeji on business and ..., accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.howwemadeitinafrica.com/build-for-the-94-nigerias-iyinoluwa-aboyeji-on-business-and-investing/182913/

-

Report: Flutterwave Business Breakdown & Founding Story | Contrary Research, accessed October 29, 2025, https://research.contrary.com/company/flutterwave

-

Meet the Healthcare Start-ups That Won the Africa Innovation Challenge 2.0, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.jnj.com/innovation/meet-the-healthcare-start-ups-that-won-the-africa-innovation-challenge-2-0

-

Thato Schermer (Zoie Health): Reshaping Women's Healthcare in South Africa | Mashstartup Podcast - YouTube, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyNlFJVvCOY

-

StrongMinds, accessed October 29, 2025, https://strongminds.org/

-

African startups face tougher scrutiny as investors seek returns, accessed October 29, 2025, https://african.business/2025/10/finance-services/african-startups-face-tougher-scrutiny-as-investors-seek-returns

-

African Proverbs - CogWeb, accessed October 29, 2025, http://cogweb.ucla.edu/Discourse/Proverbs/African.html

-

8 Business Lessons from African Proverbs - Businessday NG, accessed October 29, 2025, https://businessday.ng/bd-weekender/article/8-business-lessons-from-african-proverbs/

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0