A Go-to-Market Blueprint for Telehealth Services in the African Market: A Strategic Framework for Entry, Growth, and Sustainable Impact

A comprehensive go-to-market strategy for launching telehealth services in Africa, a market projected to reach US$16.6 billion by 2030. This report outlines a phased, hyper-localized approach to navigate the continent's diverse regulatory and socio-economic landscape. It details a tiered market entry plan, a multi-modal technology strategy embracing both high-bandwidth apps and low-bandwidth solutions like USSD and SMS, and the critical importance of building strategic partnerships to achieve scale and sustainable impact in Africa's evolving healthcare ecosystem.

Executive Summary

The African digital health market presents a generational opportunity for investment and impact, with a projected valuation of US$16.6 billion by 2030, up from US$3.8 billion in 2023.1 This explosive growth is not merely a function of technological adoption but is fundamentally driven by profound, systemic deficiencies within the continent's traditional healthcare infrastructure. Chronic underfunding, a severe human resource crisis, and vast geographical barriers to access have created a compelling and urgent need for innovative care delivery models.2 Telehealth is uniquely positioned to fill this void, offering a scalable solution to democratize healthcare access.

However, the African continent is a complex mosaic of 54 distinct markets, each with its own technological, regulatory, and socio-economic realities. A monolithic, one-size-fits-all strategy is a blueprint for failure. Success in this landscape is contingent upon a hyper-localized, multi-tiered go-to-market (GTM) strategy that is both agile and deeply attuned to local context. This report outlines such a strategy, grounded in a rigorous analysis of market dynamics, competitive intelligence, and regulatory frameworks.

The central recommendation is a phased-entry approach. Initial efforts should concentrate on Tier 1 High-Readiness Hubs—such as urban centers in South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria—where digital infrastructure and consumer purchasing power are more developed. This allows for market validation and the generation of early revenue. The subsequent phases involve scaling into Tier 2 Emerging Adopter markets like Rwanda and Ghana, often through public-private partnerships, before tackling the immense access challenges in Tier 3 Frontier and Rural Regions.

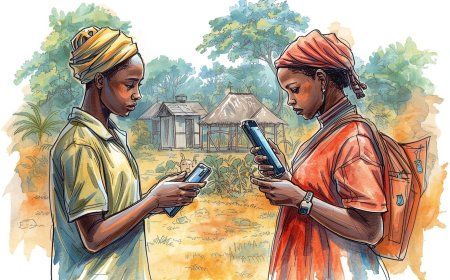

Critical to this strategy is the deployment of a multi-modal technology stack. While a feature-rich smartphone application is necessary for urban segments, true scale and inclusivity can only be achieved by embracing low-bandwidth and no-bandwidth solutions like USSD, SMS, and integration with ubiquitous platforms such as WhatsApp. This approach directly addresses the continent's significant "usage gap," where network coverage exists but is underutilized due to data costs and low digital literacy.

Furthermore, the competitive landscape reveals that the most successful ventures are not standalone technology platforms but are deeply embedded within the existing ecosystem. Therefore, this GTM plan places paramount importance on building a robust network of strategic partnerships with corporations, insurers, mobile network operators, and government bodies. Navigating the fragmented and evolving regulatory environment is not merely a compliance exercise but a core strategic function; building a reputation for trust and robust data security will be a key competitive differentiator. Ultimately, this report provides a comprehensive blueprint for any organization seeking to enter the African telehealth market, not just to achieve commercial success, but to build a sustainable and impactful presence within the continent's healthcare future.

Section 1: The African Digital Health Revolution: Market Dynamics and Opportunity Analysis

To formulate an effective go-to-market strategy, a foundational understanding of the market's size, growth drivers, and inherent challenges is imperative. The African telehealth market is characterized by a powerful confluence of factors: a rapidly growing digital economy, severe structural deficits in traditional healthcare delivery, and a complex set of barriers that demand nuanced solutions. This section dissects these dynamics to establish a clear and defensible business case.

1.1 Market Sizing and Growth Trajectory

The African digital health market is on a steep upward trajectory, signaling a significant and durable investment opportunity. In 2023, the market was valued at approximately US$3.8 billion, with projections indicating a more than fourfold increase to US$16.6 billion by 2030.1 The broader Middle East and Africa (MEA) telehealth market reinforces this trend, with an estimated size of US$4.51 billion in 2024 and a projected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 26.8% from 2025 to 2030.4

This growth is not speculative; it is a direct response to market forces catalyzed by recent global events. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a pivotal inflection point, compelling healthcare providers and patients to adopt remote care models out of necessity.5 This forced adoption broke down initial resistance and demonstrated the viability of telemedicine, creating a lasting shift in consumer and provider behavior. In South Africa, for instance, approximately 60% of patients now express a preference for virtual consultations, citing convenience and reduced travel costs.6 This momentum, born from crisis, has laid the groundwork for sustained expansion as digital solutions become integrated into the standard of care.8 The market's financial projections represent not just figures, but a fundamental transformation in how healthcare is conceived, designed, and delivered across the continent.1

1.2 Core Market Drivers: The "Push and Pull" Factors

The rapid expansion of telehealth in Africa is propelled by a dual set of forces: the "push" from the severe inadequacies of the existing healthcare systems and the "pull" from advancing technology and connectivity. Critically, the "push" factors are far more potent, framing telehealth not as a lifestyle convenience but as an essential service filling a critical void.

The "Push" from Healthcare System Deficiencies

The primary impetus for telehealth adoption is the systemic failure of conventional healthcare to meet the population's needs. This creates a powerful, demand-side driver for alternative solutions.

-

Chronic Underfunding and Fragmentation: The foundation of Africa's healthcare challenge is financial. Most African nations allocate less than 5% of their GDP to healthcare, a figure starkly below the 15% target set by the Abuja Declaration.2 This chronic underinvestment results in dilapidated infrastructure, frequent shortages of essential medicines and supplies, and a fragmented system where care quality varies dramatically between urban and rural areas.2 Telehealth offers a capital-efficient way to extend the reach of existing resources, bypassing the need for extensive physical infrastructure development.5

-

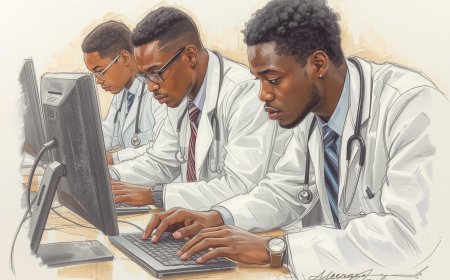

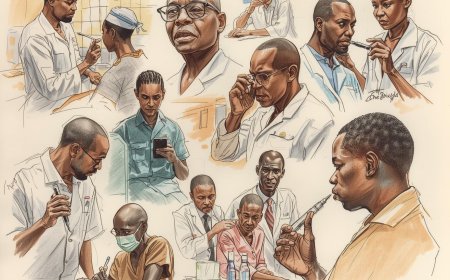

The Human Resource Crisis: The continent faces an alarming shortage of healthcare professionals. Africa shoulders 25% of the world's disease burden but is home to only 3% of its healthcare workers.2 The WHO reports an average of just one doctor per 5,000 people, far below the recommended ratio of one per 1,000.8 This crisis is exacerbated by the "brain drain" of trained professionals to higher-paying countries, leaving a critical void, especially in rural communities.2 Telehealth acts as a force multiplier, enabling a single doctor or specialist to serve a much wider geographic area and alleviating the strain on the limited workforce.8

-

Pervasive Infrastructure Gaps: Access to healthcare is profoundly unequal. Quality facilities are concentrated in urban centers, leaving rural populations geographically and economically isolated from care.10 For many, seeking medical attention involves long, costly, and often arduous journeys, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment.1 Telemedicine directly dismantles these geographical barriers, bringing care directly to patients via their mobile devices and mitigating the risks and costs associated with travel.13

-

The Double Burden of Disease: African healthcare systems are uniquely strained by a "double burden" of disease. They continue to combat high rates of infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS and malaria while simultaneously facing a rapid surge in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular conditions.2 NCDs, which now account for over 37% of deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, often require long-term, continuous management and monitoring—a care model for which telehealth is exceptionally well-suited.2 Remote patient monitoring (RPM) and regular virtual check-ups can significantly improve outcomes for this growing patient segment.

The "Pull" from Technological Advancement

While the need for better healthcare provides the "push," enabling technologies provide the "pull" that makes telehealth a viable solution.

-

Rising Mobile Penetration: The mobile phone is the primary digital gateway for the vast majority of Africans. While mobile internet penetration remains relatively low at 27-28% 16, smartphone adoption is steadily increasing and is projected to reach 90% in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region by 2030.4 This mobile-first environment is the fundamental infrastructure upon which mHealth and telemedicine services are built.13

-

Government and Private Sector Digital Transformation: There is a growing recognition among policymakers and business leaders that digital health is a critical component of national development. Governments are beginning to formulate digital health strategies, and private sector investment is flowing into the health-tech ecosystem, fostering collaborations that enhance infrastructure and expand service delivery.1 Initiatives like the Africa CDC's partnership with the GSMA to connect health facilities to the internet exemplify this top-down support for digital transformation.19

1.3 Significant Market Barriers and Headwinds

Despite the compelling opportunity, the path to market is fraught with significant challenges that must be addressed strategically.

-

The Digital Divide and Usage Gap: The most formidable barrier is the digital divide. This is not simply a matter of network coverage. A staggering "usage gap" of 60-64% persists across the continent, meaning the majority of people who live within an area of mobile broadband coverage do not actually use it.16 The primary reasons are the high cost of data plans and internet-enabled handsets, coupled with low levels of digital literacy.17 A telehealth strategy that relies solely on data-intensive smartphone apps will fail to reach the mass market.

-

Regulatory and Policy Fragmentation: The African regulatory landscape for telehealth is a patchwork of nascent, evolving, and often non-existent frameworks. There is no pan-African standard, forcing operators to navigate the unique legal requirements of each country concerning data privacy, physician licensing, and reimbursement.10 This legal ambiguity creates significant compliance burdens and operational risks.6

-

Socio-Cultural Barriers: Technology adoption is contingent on trust. A lack of public awareness about digital health solutions, patient skepticism regarding the quality of virtual care, and resistance to change among traditionally trained healthcare providers are significant hurdles.6 Overcoming this requires concerted efforts in patient education and provider training.23

-

Economic Realities: The high initial costs of developing and implementing robust telehealth platforms can be prohibitive.6 Moreover, in many markets, the absence of widespread health insurance coverage means that services must be paid for out-of-pocket. This reliance on direct consumer payments, in regions with low disposable income, limits the scalability and affordability of services, a challenge noted by innovators who are not yet integrated with government purchasing models.25

Section 2: Strategic Market Segmentation and Target Audience Prioritization

The African continent is not a single market but a collection of diverse regions and populations with vastly different needs and capabilities. A successful GTM strategy must abandon a monolithic view and instead adopt a granular, segmented approach. This allows for the efficient allocation of resources, tailored value propositions, and a phased rollout that mitigates risk. This section proposes a three-tiered framework for market entry, complemented by a detailed analysis of key user personas.

2.1 A Tiered Approach to Market Entry

To deconstruct the complexity of the African market, countries and regions can be categorized into three tiers based on their readiness for advanced telehealth adoption. This framework guides prioritization for market entry and product strategy.

Tier 1: High-Readiness Hubs

These markets represent the most immediate commercial opportunity and are ideal for initial market entry. They are typically characterized by major urban centers with more developed infrastructure, higher disposable incomes, and a more mature regulatory environment.

-

Defining Characteristics: Higher smartphone and internet penetration, a growing tech-savvy middle class, greater availability of private health insurance, and more established (though still complex) digital health regulations.

-

Exemplary Markets: South Africa, Kenya, Egypt, and the urban centers of Nigeria (e.g., Lagos, Abuja).

-

Strategic Focus: Launch feature-rich, app-based services targeting convenience, on-demand primary care, and specialized consultations. The value proposition for this tier is often about saving time and gaining access to specialists. Evidence shows South Africa has the continent's highest adoption rate, with a focus on specialist teleconsultations and chronic disease management.13 Kenya has demonstrated strong integration of mobile health (mHealth) solutions, and key cities like Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban are the epicenters of the South African market.6

Tier 2: Emerging Adopters

These markets are characterized by strong political will for digital transformation and rapidly improving infrastructure, but they often have lower per-capita income and less developed private sectors. Success in this tier is heavily reliant on partnerships.

-

Defining Characteristics: Proactive government support for digital health, improving connectivity, a strong focus on achieving universal health coverage, and a greater role for public-private partnerships (PPPs).

-

Exemplary Markets: Rwanda, Ghana, Uganda.

-

Strategic Focus: Deploy models that align with national health priorities, such as improving primary care access. Partnership-led approaches, particularly with government bodies and national insurers, are the most viable path to scale. Rwanda's national-scale partnership with Babyl, which integrated the service into its community-based health insurance scheme, is the quintessential example of this model's potential.25 Similarly, Ghana's successful adoption of Zipline for medical drone delivery showcases a government's willingness to embrace technological solutions to healthcare challenges.28

Tier 3: Frontier/Rural-Focus Regions

These regions represent the greatest need but also the most significant operational challenges. The primary goal in this tier is not direct monetization but achieving massive scale and social impact, which can later be leveraged through government or donor funding.

-

Defining Characteristics: Severe deficits in both healthcare and digital infrastructure, low digital literacy, minimal disposable income, and often, political instability.

-

Exemplary Markets: Rural areas across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), particularly in countries like Chad, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as underserved regions within Tier 1 and 2 nations.

-

Strategic Focus: Deploy lightweight, low-bandwidth, and highly affordable (or free) technology. Solutions must be extremely simple, relying on USSD and SMS rather than data-intensive apps.13 The GTM model must be deeply integrated with on-the-ground networks, such as community health workers (CHWs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), who can facilitate "assisted telemedicine" sessions and build local trust. The fundamental challenge here is bridging the gap for populations suffering from the most acute healthcare shortages.2

2.2 Defining Key User Personas

Within these market tiers, several distinct user archetypes emerge. A successful product and marketing strategy must speak directly to the unique needs, motivations, and constraints of each.

-

Persona A: The Urban Professional (Tier 1): This user is a salaried employee or entrepreneur living in a major city like Nairobi or Johannesburg. They are tech-savvy, own a smartphone, and have reliable internet access. Their primary pain point is the inconvenience of traditional healthcare: long waiting times, traffic, and taking time off work. They value on-demand access and are willing to pay a premium out-of-pocket for quick consultations for themselves and their families, particularly for primary care, mental health support, and wellness services.

-

Persona B: The Chronic Disease Patient (Tiers 1 & 2): This persona represents one of the most valuable and impactful segments. They live with a non-communicable disease (NCD) like diabetes, hypertension, or a cardiovascular condition, which are rapidly rising across the continent.2 Their need is not for one-off consultations but for continuous, long-term care management. They require regular monitoring, easy access to specialist advice, medication reminders, and adherence support. This persona is the ideal user for Remote Patient Monitoring (RPM) services and integrated care plans, representing a high-lifetime-value (LTV) customer who can achieve significantly better health outcomes through telehealth.13

-

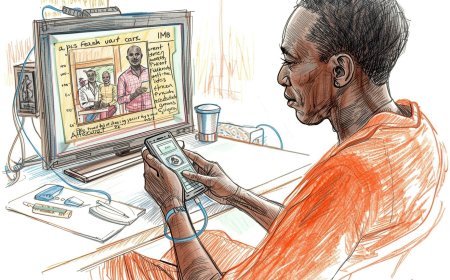

Persona C: The Rural Family (Tiers 2 & 3): This user, typically a mother, is the primary healthcare decision-maker for her family in a rural or remote area. She faces immense barriers to care, including long distances to the nearest clinic, prohibitive travel costs, and a lack of local specialists.10 Her digital literacy may be limited, and she may not own a smartphone. Her primary need is access to basic, affordable healthcare for common childhood illnesses, maternal health questions, and first-line treatment advice. She is best reached through low-tech channels (USSD/SMS) and trusted local intermediaries like CHWs.

-

Persona D: The Corporate Employee (Tiers 1 & 2): This user accesses telehealth not as an individual consumer but as a benefit provided by their employer. This B2B2C (Business-to-Business-to-Consumer) channel is a highly efficient acquisition strategy. The service is often positioned as a modern employee wellness benefit that reduces absenteeism and improves productivity. Zuri Health's "Zuri Care" for SMEs and corporates is a prime example of a product tailored specifically for this persona and the companies that employ them.29

-

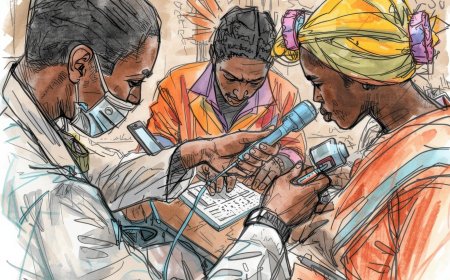

Persona E: The Healthcare Provider: This crucial user is often overlooked. Whether a doctor, nurse, or clinical officer, their adoption is critical for the platform's success. Their primary need is a system that is intuitive, integrates seamlessly into their existing workflow, reduces their administrative burden, and does not increase their workload without adequate compensation. Resistance to change among providers is a documented barrier 6, making it essential to design the platform with their needs in mind and provide comprehensive training and support.

The strategic sequencing of targeting these personas is critical. While Urban Professionals and Corporate Employees in Tier 1 markets provide the quickest path to revenue, the long-term, sustainable, and high-impact opportunity lies in building a robust platform for Chronic Disease Patients. The volume and need of the Rural Family represent the path to mass-market scale, typically unlocked through partnerships. A successful GTM plan will use the former to establish a beachhead while strategically building the capabilities to serve the latter.

Section 3: Crafting the Value Proposition and Service Offering

A clear understanding of the market and its target users must translate into a tangible product and a viable business model. For the diverse African context, this requires a modular service portfolio that can be adapted to different market tiers, a multi-modal technology strategy that ensures accessibility across the digital divide, and a flexible pricing structure that aligns with local economic realities.

3.1 The Core Service Portfolio

A successful telehealth platform in Africa cannot be a single-feature product. It must offer a spectrum of services that can be deployed modularly based on the target market's needs and maturity.

Foundational Services (Applicable to All Tiers)

These are the essential, non-negotiable components of any telehealth offering.

-

General Consultations: The core service is providing access to general practitioners (GPs) and clinical officers. This must be offered through multiple modalities to ensure accessibility: real-time interactions via video, audio, or live chat for users with sufficient bandwidth, and asynchronous "store-and-forward" services (e.g., sending a photo of a skin condition for later review) for low-connectivity environments.4

-

E-Prescriptions and Medication Delivery: A consultation is incomplete if it does not lead to a clear treatment path. The platform must have the capability to generate electronic prescriptions and, crucially, integrate with a network of local, vetted pharmacies for fulfillment and delivery. This closes the loop for the patient and is a key feature of platforms like Zuri Health and Vezeeta.30

-

Lab and Diagnostic Referrals: Since virtual consultations cannot perform physical examinations, a seamless referral system is essential. The platform must build a partnership network of trusted local laboratories and diagnostic centers to which patients can be directed for necessary tests, with results transmitted back to the platform.30

Advanced Services (Targeted at Tier 1 & 2)

These services cater to users with more specific needs and often represent higher-margin revenue streams.

-

Specialist Care: This is a major value proposition, as specialists are critically scarce outside of major urban hubs.2 The platform should focus on high-demand specialties with a strong business case for remote delivery. Key areas include teleradiology, telecardiology, teledermatology, and pediatrics.4 Telepsychiatry presents a particularly compelling opportunity, as it addresses both a shortage of mental health practitioners and helps overcome the social stigma associated with seeking in-person mental healthcare.4

-

Chronic Disease Management and Remote Patient Monitoring (RPM): This service targets the high-LTV Persona B. It involves structured programs for managing conditions like diabetes and hypertension, often incorporating data from connected IoT devices such as Bluetooth-enabled blood pressure meters and glucose monitors.4 This proactive model improves health outcomes and creates a "sticky" long-term relationship with the patient. DRO Health's sale of its own branded BP monitor is a clear strategic move into this space.33

-

Corporate Wellness Programs: This is a B2B offering tailored to Persona D. These are packaged services sold to companies on a subscription basis, typically including unlimited GP consultations, mental health support, nutritional counseling, and wellness workshops for their employees. Zuri Care's model demonstrates the demand for such comprehensive corporate health solutions.29

Rural-Focused Services (Essential for Tier 3)

These services are designed for maximum reach and accessibility in low-resource settings.

-

mHealth and Health Education: Leveraging the ubiquity of basic mobile phones, these services use SMS and USSD to deliver vital health information, vaccination reminders, medication adherence prompts, and maternal health tips.13

-

Assisted Telemedicine: This model addresses the digital literacy gap head-on. It involves equipping a local community health worker (CHW) or a nurse at a small clinic with a tablet and internet access. The CHW facilitates the consultation between the patient and a remote doctor, acting as a trusted intermediary who can help operate the technology and explain medical advice.

3.2 The Multi-Modal Technology Strategy

The choice of technology is the most critical determinant of market access. A platform built only for the latest smartphones will exclude the majority of the potential user base. A truly inclusive strategy must be multi-modal.

-

High-Bandwidth Channels: For Tier 1 users, a full-featured native smartphone app (for iOS and Android) and a comprehensive web-based platform are essential. These channels can support high-quality video consultations and a rich user interface.4

-

Low-Bandwidth Optimization: The platform must include a "lite" version of the app or a mobile-optimized website that functions effectively on slower 2G or 3G connections and uses minimal data.

-

No-Bandwidth Channels (USSD/SMS): For the vast population in Tier 3 without consistent internet access, Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) and SMS are vital. Users should be able to register, book appointments, receive prescriptions, and get health reminders through simple, text-based menus that work on any mobile phone.13 Babyl's initial success in Rwanda was built on its effective use of a USSD platform.27

-

Partnership-Based Channels (Super Apps): Instead of forcing users to download a new app, the service should integrate into platforms they already use daily. Leveraging the WhatsApp Business API is a powerful strategy, as demonstrated by Zuri Health and Praekelt.org's government service in South Africa.28 This dramatically lowers the barrier to entry for users.

-

Backend Infrastructure: The entire system must be built on a scalable, secure, and reliable cloud-based infrastructure.4 A core architectural principle must be interoperability—the ability to securely exchange data with external systems like Electronic Medical Records (EMRs), pharmacy management systems, and national health information systems is crucial for long-term integration into the healthcare ecosystem.18

3.3 Pricing and Monetization Models

Pricing cannot be uniform across the continent; it must be flexible and localized to reflect vast differences in purchasing power and payment habits.

-

Pay-Per-Consultation (B2C): This is the most straightforward model for individual, out-of-pocket users. Pricing must be highly sensitive to the local market. For example, a virtual consultation with Hello Doctor in South Africa is priced at R278 (approximately US$15) [36], whereas a consultation on DRO Health in Nigeria can be as low as ₦1500 (approximately US$1-2).33 This highlights the necessity of country-specific pricing strategies.

-

Subscription Models (B2C/B2B): Offering monthly or annual plans for individuals, families, or businesses can create a predictable, recurring revenue stream. This model is well-suited for chronic disease management programs and corporate wellness packages. Vezeeta and others have incorporated subscription options into their offerings.31

-

Corporate Contracts (B2B): A dedicated B2B sales effort targeting companies with per-employee-per-month (PEPM) pricing is a highly effective channel. This model, used by Zuri Care, provides stable revenue and acquires users in bulk.29

-

Freemium Model: This model can be a powerful tool for user acquisition and education. It involves offering basic services for free—such as an AI-powered symptom checker, access to a health content library, or simple text-based advice—while charging for premium services like live consultations with a doctor. Hello Doctor successfully employs a version of this, offering a free advice service to drive engagement for its paid virtual consultations.36

-

Public-Private Partnership (PPP) / Insurance Integration: This is the key to unlocking the mass market and achieving true scale. In this model, the government or a major insurer covers the cost of consultations for its members. The Babyl-Rwanda government partnership is the prime example 27, and Hello Doctor's deep integration with Momentum Health in South Africa demonstrates the viability of the private insurance route.36 Securing such a partnership is a complex, long-term endeavor but offers the greatest potential for widespread impact and sustainability.

Section 4: Competitive Intelligence and Strategic Positioning

The African telehealth market, while nascent, is becoming increasingly crowded with a mix of local innovators, regional champions, and international players. A successful GTM plan requires a sophisticated understanding of this competitive landscape to carve out a unique and defensible market position. Simply launching a generic teleconsultation app is no longer a viable strategy. Differentiation must be deliberate and rooted in a clear understanding of what competitors do well and where their weaknesses lie.

4.1 Analysis of Key Competitors

An analysis of the leading telehealth and health-tech players across the continent reveals distinct strategic approaches and business models. A new entrant must understand these archetypes to inform its own strategy.

-

Zuri Health (Kenya-based, Pan-African ambition): Zuri Health embodies the "Integrator" model. Its strategy is to become a comprehensive, one-stop-shop digital health platform. The service portfolio is broad, encompassing not only virtual consultations (via app and WhatsApp) but also at-home doctor visits, lab test booking, and pharmacy services.30 A key strength is its well-developed B2B offering, "Zuri Care," which targets corporates and SMEs with employee health packages, providing a stable revenue stream and an efficient customer acquisition channel.29 Zuri's approach is to build a horizontal platform that captures multiple points of the patient journey.

-

Babyl (Rwanda): Babyl represents the "Government Partner" model. Its path to scale was not through traditional B2C or B2B marketing but through a landmark 10-year partnership with the Rwandan government. This deep integration with the national community-based health insurance scheme (Mutuelle de Santé) gave it access to millions of citizens, making it a core part of the national healthcare delivery system.25 While this strategy achieved unparalleled scale, its recent reported winding down of operations highlights the risks of dependency on a single, large-scale contract and the challenges of long-term financial sustainability in a PPP model.40

-

Vezeeta (Egypt-based, MENA focus): Vezeeta's strategy is that of a "Marketplace." Originating as a doctor discovery and appointment booking platform, it has since expanded into telehealth, e-pharmacy, and at-home visits.31 Its core strength lies in its large, searchable database of healthcare providers, empowering patient choice. Operating primarily in North Africa and the Middle East, its model is focused on aggregating both supply (doctors) and demand (patients) and facilitating their connection, monetizing through booking fees, subscriptions, and other services.25

-

DRO Health (Nigeria): DRO Health is a prime example of a "Niche Specialist" focusing on building an integrated hardware-software ecosystem. While it offers general teleconsultations, its key differentiator is the sale of its own branded remote monitoring devices, such as a Bluetooth-enabled blood pressure monitor that syncs with its app.33 This positions DRO Health strongly within the high-value chronic disease management segment, creating a sticky product ecosystem and a defensible moat against competitors offering only consultations.25

-

mPharma (Pan-African): While not a direct competitor in teleconsultations, mPharma is a critical ecosystem player and a potential partner, representing the "Supply Chain Specialist" model. Its entire business is built around solving the problem of medicine affordability and accessibility. It achieves this through innovative financing, inventory management solutions for pharmacies and hospitals, and a patient savings program called Mutti.43 Its focus on the pharmaceutical supply chain makes it a powerful potential ally for any telehealth platform looking to ensure reliable e-prescription fulfillment.25

-

Hello Doctor (South Africa): Hello Doctor exemplifies the "Insurance Partner" model. Its primary distribution channel is its deep partnership with Momentum, a major South African health insurer.36 This provides immediate access to a large base of potential users. Its GTM strategy is further distinguished by a freemium model, where basic telephonic advice is free to members, which serves as a powerful top-of-funnel tool to upsell users to paid virtual consultations for diagnosis and prescriptions.37

4.2 Competitive Landscape Overview Table

The following table synthesizes the analysis of these key players, providing a scannable overview of their strategic postures. This tool is essential for identifying gaps in the market and opportunities for differentiation.

|

Competitor |

Key Markets |

Core Service Offerings |

Technology Platform |

Monetization Strategy |

Key Differentiator |

|

Zuri Health |

Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, etc. |

Virtual Consultations, At-Home Visits, Lab/Pharmacy Booking, Corporate Wellness |

App, Web, WhatsApp |

B2C Pay-per-use, B2B Subscriptions (Zuri Care) |

Comprehensive, one-stop-shop service integration 29 |

|

Babyl |

Rwanda |

AI Triage, Virtual Consultations |

USSD, App |

Public-Private Partnership (Gov't Insurance) |

Deep national government integration and scale 25 |

|

Vezeeta |

Egypt, Nigeria, Kenya |

Doctor Booking, Telehealth, e-Pharmacy, Home Visits |

App, Web |

B2C Pay-per-use, Subscriptions |

Strong doctor discovery and booking marketplace model 25 |

|

DRO Health |

Nigeria |

Virtual Consultations, EMR for Providers, Wellness, RPM Devices |

App, Web |

B2C Pay-per-use, B2B, Direct Product Sales |

Integrated hardware-software ecosystem for chronic care 25 |

|

mPharma |

9 African countries |

Medicine Financing, Inventory Management, Patient Savings Program (Mutti) |

B2B Platform |

B2B Service Fees, Patient Financing |

Focus on pharmaceutical supply chain and affordability 25 |

|

Hello Doctor |

South Africa |

GP Advice, Virtual Consultations, e-Prescriptions |

App, USSD |

Freemium (basic advice free), Insurance Partnership (Momentum) |

Freemium model and deep integration with a major insurer 36 |

This competitive analysis reveals that the market is not monolithic. Instead, several distinct and potentially successful strategic paths are being forged. A new entrant cannot simply replicate an existing model but must consciously decide which path to pursue or how to create a novel blend. For example, a company could attempt to combine Zuri's integrated service model with DRO Health's niche focus on chronic care, creating a powerful offering for a high-value patient segment. Alternatively, it could focus its entire effort on securing a government partnership in a Tier 2 country, following the Babyl playbook. This strategic choice is fundamental and will dictate priorities across hiring, product development, and capital allocation. Trying to be an integrator, a government partner, and a niche specialist simultaneously is a recipe for diluted focus and market failure.

Section 5: Navigating the Regulatory and Compliance Landscape

Beyond market forces and competitive pressures, the single most critical factor determining the viability of a telehealth operation in Africa is the ability to navigate its complex and fragmented regulatory landscape. Each country presents a unique set of rules governing medical practice, data privacy, and consumer protection. Treating compliance as a mere legal hurdle is a strategic error; instead, it must be embraced as a core business function and a source of competitive advantage. The platform that builds the deepest trust with regulators, providers, and patients will ultimately win.

5.1 Country-Specific Regulatory Deep Dives

A pan-African rollout requires a country-by-country approach to compliance. The legal frameworks in key Tier 1 and Tier 2 markets illustrate the diversity of the challenge.

-

South Africa: The regulatory environment here is among the most mature on the continent, which also makes it one of the most stringent. Telehealth practice is primarily governed by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) through its "General Ethical Guidelines for Good Practice in Telehealth".46 A key requirement is that any practitioner providing telehealth services must be registered with the HPCSA. This extends to cross-border consultations; a doctor in another country serving a South African patient must be registered in their home country and with the HPCSA, creating a significant barrier to using international doctor networks.46 Furthermore, all handling of patient data is subject to the rigorous Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013 (POPIA), which mandates strict protocols for data safety, consent, and cross-border data transfer.46

-

Nigeria: Nigeria represents a more fragmented landscape, currently lacking a single, dedicated piece of telehealth legislation.48 Compliance is a matter of navigating multiple intersecting laws. The Constitution of Nigeria guarantees a right to privacy for communications, which extends to telehealth consultations. The Nigeria Data Protection Act 2023 (NDPA) is the primary law governing patient data, requiring telemedicine platforms to register with the Nigeria Data Protection Commission (NDPC) as data controllers/processors and to implement robust security measures like encryption.48 The National Health Act 2014 provides the legal framework for the healthcare system and mandates the protection of patient records from unauthorized access. Finally, the Code of Medical Ethics explicitly recognizes telemedicine, underscoring the need for patient confidentiality.48 Operationally, this requires local company incorporation and adherence to multiple legal statutes.

-

Kenya: Kenya is in the process of formalizing its e-health framework through legislation like the County E-Health Bill, 2021.50 This proposed law signals the government's direction, placing a strong emphasis on creating an integrated national e-health system. The principles guiding this framework are clear: guaranteeing patient information rights and confidentiality, ensuring the security of data exchange, and requiring explicit patient consent for the delivery of e-health services. The policy aims to integrate e-health into the existing public health system at both national and county levels, indicating that future success will likely depend on a provider's ability to interoperate with government systems.50

-

Rwanda: Rwanda has emerged as the most progressive and clear regulatory environment for digital health in Africa. The landmark Law N° 026/2025 fundamentally modernizes the country's healthcare framework and, crucially, formally ushers it into the digital age.51 Articles 37-39 of this law explicitly recognize, permit, and regulate digital health and telemedicine. A key provision is the mandate in Article 38 that any entity providing healthcare services through digital means must obtain a specific license to do so.51 Article 39 imposes a direct legal obligation on providers to ensure the security and confidentiality of patient data, which is classified as "sensitive personal data" under Rwanda's comprehensive data protection law (Law N° 058/2021).51 This clear, forward-looking legal framework reduces ambiguity and provides a stable foundation for investment and operation.

5.2 A Pan-African Compliance Framework

While country-specific rules must be followed, a set of core principles can guide the development of a scalable, pan-African compliance engine.

-

Data Sovereignty and Privacy by Design: The platform's architecture must be built on the principle of "privacy by design." Assume that all health data is sensitive and must be handled according to the strictest applicable local law, whether it be South Africa's POPIA or Nigeria's NDPA. A critical consideration is data sovereignty; plan for the possibility of data localization laws that require patient data to be stored on servers within the country's borders. Compliance with international standards like HIPAA, as marketed by Zuri Health 30, can serve as a strong baseline, but local laws are paramount.

-

Rigorous Physician Licensing and Verification: The credibility of the entire platform rests on the quality and legitimacy of its healthcare providers. This is the cornerstone of trust and legality.

-

The Challenge: Manually verifying the credentials of thousands of doctors across 54 different national medical councils, each with its own standards and processes, is a monumental operational task.

-

Best Practice Framework: A multi-step, auditable verification process is non-negotiable. This should include: 1) Primary Source Verification: Directly confirming a provider's registration and good standing with the relevant national medical and dental council. 2) Background Checks: Conducting checks for any history of malpractice or ethical violations. 3) Platform-Specific Training: Mandating that all onboarded providers complete training modules on telehealth best practices, platform usage, and local digital health regulations. 4) Phased Recruitment: To mitigate risk, the initial strategy in any new market should be to recruit and license doctors who are physically located and licensed within that country. This avoids the immediate complexities of cross-border practice regulations, such as South Africa's dual-registration requirement.46

-

Explicit and Documented Informed Consent: Consent cannot be buried in lengthy terms and conditions. The platform must obtain explicit, informed consent from the patient for two distinct things: consent for the medical treatment itself, and consent for the use of a digital platform to deliver that care.47 This process must be clear, presented in simple language, and securely documented for every consultation.

-

Compliant E-Prescription Workflows: The rules governing electronic prescriptions vary significantly. A viable strategy cannot assume that a digital prescription generated on the platform is automatically valid everywhere. The solution is to build a closed-loop system through partnerships. This involves integrating with a network of certified local pharmacies that can receive, validate, and dispense medications in full compliance with local pharmaceutical regulations.47

By proactively building a robust compliance infrastructure, a telehealth company can transform a potential liability into a powerful asset. Marketing materials should prominently feature commitments to data security and patient privacy. The ability to demonstrate a deep understanding of and adherence to local regulations will build trust not only with patients but also with potential government and corporate partners, paving the way for deeper, more strategic collaborations.

Section 6: The Go-to-Market Action Plan: Channels, Marketing, and Partnerships

A sound strategy is only as good as its execution. This section translates the preceding analysis into an actionable plan for reaching, acquiring, and retaining customers. The approach must be multi-channeled and deeply integrated, recognizing that customer acquisition in Africa is rarely a simple digital transaction. It requires a blend of modern marketing techniques, on-the-ground community engagement, and a robust ecosystem of strategic partnerships.

6.1 Distribution and Customer Acquisition Channels

The channels used to reach customers must be as diverse as the target personas themselves, tailored to the infrastructure and media consumption habits of each market tier.

-

Digital Marketing (Primarily for Tier 1): For reaching the Urban Professional (Persona A) in cities like Lagos, Nairobi, and Cape Town, a sophisticated digital marketing strategy is effective. This includes targeted advertising on social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn), search engine marketing (SEM) to capture users actively searching for healthcare solutions, and content marketing. A content strategy focused on a health and wellness blog, offering tips on prevalent local health issues, can build brand authority and attract organic traffic.

-

B2B Corporate Sales (Tiers 1 & 2): This is one of the most efficient and scalable acquisition channels. A dedicated enterprise sales team should be established to target SMEs and large corporations with tailored employee wellness packages, as done by Zuri Health.29 This B2B2C approach (selling to the business to reach the consumer) provides access to a large pool of users (Persona D) at once and generates stable, recurring revenue. The value proposition for employers is clear: reduced absenteeism, increased productivity, and a modern, attractive employee benefit.

-

Community-Level Engagement (Tiers 2 & 3): Reaching the Rural Family (Persona C) requires a high-touch, trust-based approach that goes far beyond digital ads.

-

Community Health Worker (CHW) Partnerships: CHWs are a trusted and established part of the healthcare fabric in many rural communities. Partnering with them is essential. This involves equipping CHWs with tablets, data plans, and training, empowering them to become facilitators for "assisted telemedicine" sessions. They can onboard new users, assist with the technology, and help translate medical advice into a local context.

-

Collaboration with Local Leaders and NGOs: Building trust at the community level requires engaging with local influencers such as village elders, religious leaders, and community associations. Partnering with health-focused NGOs that already have a presence and trusted relationships in these areas can significantly accelerate adoption and lend credibility to the service.

-

Mobile Network Operator (MNO) Partnerships: MNOs are perhaps the most powerful potential distribution partners in Africa. A strategic collaboration can address the critical barrier of data affordability. This can take several forms: negotiating zero-rated data access for the telehealth app (so usage does not consume a user's data plan), bundling telehealth subscriptions with mobile or data plans, and leveraging the MNO's established billing infrastructure for easy payment. The GSMA is actively fostering such partnerships to advance mHealth initiatives across the continent.19

6.2 Culturally-Aware Marketing and Communications Strategy

Marketing messages cannot simply be translated; they must be culturally adapted to resonate with local values, languages, and health concerns. The central theme of all communication must be building trust.

-

Leading with Public Health Messaging: The most effective marketing campaigns will focus on education and empowerment rather than just technological convenience. A powerful case study is the campaign supporting South Africa's sugary drink tax.52 The campaign, "Are You Drinking Yourself Sick?", first focused on raising public awareness of the health harms of sugary drinks. Only after establishing this foundation of understanding did it pivot to advocating for the policy solution. This approach built broad public support and demonstrated the power of leading with a relatable public health message. For telehealth, this means launching mass media campaigns on widely consumed channels like radio and local television, in local languages, that address prevalent health issues (e.g., hypertension management, malaria prevention, maternal health) and position the service as an accessible, trustworthy solution.

-

Hyper-Localization of Content: All user-facing materials—from the app interface and website copy to marketing advertisements and health education content—must be professionally translated and culturally adapted for each target market. Support for multiple local languages is not an optional feature but a core requirement for inclusivity and usability.53

-

Leveraging Social Proof and Testimonials: Trust is built through shared experience. A key part of the marketing strategy should be to collect and promote testimonials from real, local patients and doctors. These stories, shared through video or text, can demystify the service, demonstrate its real-world benefits, and provide the social proof needed to overcome skepticism among new users.

6.3 Building a Strategic Partnership Ecosystem

In the African context, no telehealth company can achieve significant scale in isolation. Success is a team sport, requiring the creation of a deeply integrated ecosystem of partners.

-

Public Sector Engagement: Building relationships with Ministries of Health, national health insurance funds, and public health agencies is a long-term strategic imperative. While complex and time-consuming, a formal Public-Private Partnership (PPP) offers the greatest potential for scale and impact, as the Babyl-Rwanda model showed.10 Engaging with pan-African bodies like the Africa CDC, which is actively promoting digital health solutions through initiatives like the Africa HealthTech Marketplace, can also provide credibility and strategic alignment.19 The private sector has a significant and growing role in health service delivery, and formal engagement is a priority for many governments.55

-

Private Sector Alliances:

-

Insurers: Integrating with private health insurance companies allows for direct billing and co-payment, making the service more affordable and accessible for insured individuals. The Hello Doctor-Momentum partnership is a benchmark for this model's success in acquiring a large user base.36

-

Pharmacies and Laboratories: As previously mentioned, a robust, nationwide network of fulfillment partners for prescriptions and diagnostic tests is operationally essential. These are not just vendors but critical partners in delivering a complete patient experience.

-

Mobile Network Operators (MNOs): These are the gatekeepers to the mobile-first consumer. Partnerships are critical for distribution, marketing reach, and solving the data affordability problem.

-

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs): Health-focused NGOs often have deep roots and high levels of trust within the rural and underserved communities that are hardest to reach. Partnering with them can provide immediate access and credibility, allowing the telehealth service to be integrated into existing community health programs.

The analysis strongly suggests that a B2B2C model, executed through these diverse partnerships, is the most effective and capital-efficient path to scale. While direct-to-consumer digital advertising has its place in Tier 1 markets, the real growth engine lies in leveraging the established customer bases, distribution channels, and brand trust of corporate, insurance, and telecommunications partners. This strategic focus requires building a world-class partnership and enterprise sales team, shifting the primary growth metric from "individual app downloads" to the more strategic "number of lives covered by partnerships."

Section 7: Strategic Recommendations and Implementation Roadmap

Synthesizing the comprehensive analysis of the African telehealth market, this final section provides a clear, actionable, and phased implementation plan. This roadmap is designed to de-risk market entry, allow for iterative learning, and build a sustainable foundation for long-term growth and impact. It is underpinned by a set of critical success factors that must remain at the core of the strategy throughout its execution.

7.1 Phased Implementation Roadmap

A sequential, three-phase approach is recommended to manage capital, navigate complexity, and build capabilities over a five-year horizon.

Phase 1 (Year 1): Market Entry and Validation

This initial phase is focused on establishing a beachhead in a single, high-potential market to validate the product, business model, and operational playbook.

-

Geographic Focus: Launch operations in one Tier 1 city with a favorable combination of infrastructure, market size, and regulatory clarity (e.g., Nairobi, Kenya, or Lagos, Nigeria).

-

Core Actions:

-

Legal and Regulatory: Establish a local legal entity, secure all necessary business and health-tech licenses, and ensure full compliance with local data protection laws (e.g., NDPA in Nigeria).

-

Team Building: Recruit a core local team, including a country manager, a head of medical operations, and a partnership lead. Begin the rigorous process of recruiting and credentialing an initial cohort of local doctors.

-

Partnership Network: Build an initial network of partner pharmacies and laboratories within the launch city to ensure a closed-loop service for prescriptions and diagnostics.

-

Product Launch: Deploy a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) featuring the core service portfolio: pay-per-use GP consultations delivered via a smartphone app, a web portal, and, critically, a WhatsApp channel.

-

Customer Acquisition: Focus on two primary channels: targeted digital marketing to acquire early-adopter Urban Professionals (Persona A) and a dedicated B2B sales effort to secure the first 5-10 corporate clients (Persona D).

-

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): Number of completed consultations, number of active users (patients and providers), provider satisfaction rate, Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), Average Revenue Per User (ARPU), and number of B2B contracts signed.

Phase 2 (Years 2-3): Expansion and Service Deepening

With a validated model, this phase focuses on scaling within the initial country and expanding the product's value proposition to increase user retention and lifetime value.

-

Geographic Focus: Expand services to other Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities within the launch country. Begin formal market analysis for entry into a second Tier 1 country.

-

Core Actions:

-

Service Expansion: Launch advanced service modules, prioritizing high-demand specialist care such as telepsychiatry and teledermatology.

-

Monetization Evolution: Introduce subscription plans for individuals, families, and corporates to build a recurring revenue base.

-

Chronic Care Pilot: Pilot a chronic disease management program for hypertension or diabetes, incorporating integrated remote monitoring devices. This targets the high-LTV Persona B.

-

Strategic Partnerships: Actively pursue a large-scale strategic partnership with a major national health insurer or a leading MNO to dramatically expand reach and address affordability.

-

KPIs: Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR), subscription revenue as a percentage of total revenue, chronic care patient enrollment and adherence rates, user retention and churn rates, and number of lives covered by insurance/telco partnerships.

Phase 3 (Years 4-5): Scaling for Access and Impact

This phase marks the transition from a commercially focused urban service to a mass-market platform aimed at achieving significant scale and social impact, particularly in underserved areas.

-

Geographic Focus: Achieve nationwide coverage in the initial country/countries. Execute entry into a second and potentially third country, including a Tier 2 market.

-

Core Actions:

-

Technology for Inclusion: Roll out and heavily promote USSD-based services for registration, booking, and health information to bridge the digital divide.

-

Government Engagement: Formalize Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) with Ministries of Health or national health insurance schemes to integrate the service into the public healthcare system.

-

Rural Expansion Model: Deploy the "assisted telemedicine" model at scale by building a formal network of trained and equipped Community Health Workers (CHWs) in partnership with local NGOs.

-

Platform Ecosystem: Evolve the platform to become a central piece of digital health infrastructure, with robust APIs for integration with other health-tech solutions (e.g., EMRs, supply chain platforms like mPharma).

-

KPIs: Percentage of user base in rural areas, number of government- or donor-funded consultations, geographic coverage percentage, and key impact metrics (e.g., patient travel costs saved, reduction in clinic wait times).

7.2 Critical Success Factors and Final Recommendations

To successfully execute this roadmap, the organization must embed the following principles into its culture, strategy, and operations:

-

Embrace Hyper-Localization: A "one-size-fits-Africa" approach will fail. Every element of the strategy—from the pricing of a consultation and the language of a marketing campaign to the choice of technology and the structure of a partnership—must be meticulously tailored to the specific context of each country, city, and community.

-

Prioritize Trust Above All: In healthcare, trust is the ultimate currency. This requires an unwavering commitment to the highest standards of data security, transparent communication with patients about their data, and a rigorous, auditable process for verifying and training all healthcare providers on the platform. "Trust and Safety" should not be a compliance function but a core, marketable product feature.

-

Build for the "Usage Gap," Not Just the Coverage Gap: The greatest barrier to scale is not a lack of network towers but the affordability of data and devices, and low digital literacy. A technology strategy that does not prioritize multi-modal access through low-bandwidth and no-bandwidth channels like USSD and WhatsApp is a strategy that willingly ignores the majority of the addressable market.

-

Lead with Partnerships: The most sustainable and capital-efficient path to scale is through a B2B2C model. Building a world-class team dedicated to forging deep, long-term partnerships with corporations, insurers, MNOs, and governments is more critical than building a massive direct-to-consumer marketing engine.

-

Adopt a Long-Term Vision: The challenges in African healthcare are profound, and the solutions will not be built overnight. Success in this market is a marathon, not a sprint. It demands patience, operational resilience, a deep-seated cultural understanding, and a genuine commitment to solving fundamental healthcare access problems. The ultimate strategic objective should be to transcend being merely a technology application and become an indispensable, integrated part of each nation's healthcare infrastructure.

Works cited

-

How Digital Networks Are Reshaping Healthcare in Africa, accessed October 27, 2025, https://ehealthafrica.org/how-digital-networks-reshaping-healthcare-africa/

-

The Future of Healthcare in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities ..., accessed October 27, 2025, https://accessh.org/opinions/the-future-of-healthcare-in-africa-challenges-and-opportunities/

-

Bridging the gap: Strengthening health systems through a resilient ..., accessed October 27, 2025, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/health/Bridging-the-gap-Strengthening-health-systems

-

Middle East And Africa Telehealth Market Size Report, 2030, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/middle-east-africa-telehealth-market-report

-

Digital Health Innovations in Africa: Harnessing AI, Telemedicine, and Personalized Medicine for Improved Healthcare - Frontiers, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/62391/digital-health-innovations-in-africa-harnessing-ai-telemedicine-and-personalized-medicine-for-improved-healthcare

-

South Africa Telemedicine Market | 2019 – 2030 | Ken Research, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.kenresearch.com/south-africa-e-health-and-telemedicine-market

-

Middle East and Africa Telehealth Market Report – Industry Trends and Forecast to 2029, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.databridgemarketresearch.com/reports/middle-east-and-africa-telehealth-market

-

Telemedicine as a Catalyst for Change in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evaluating Organizational, Technological, and Social Factors, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.texilajournal.com/thumbs/article/21_TJ2978.pdf

-

Africa's Health Financing Gap | Think Global Health, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/africas-health-financing-gap

-

Telemedicine in rural Africa: A review of accessibility and impact - World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, accessed October 27, 2025, https://wjarr.com/sites/default/files/WJARR-2024-0475.pdf

-

African Development Bank and Partners Unveil Guidance to Transform Healthcare Infrastructure in Africa, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/african-development-bank-and-partners-unveil-guidance-transform-healthcare-infrastructure-africa-79525

-

There is an urgent need for a global rural health research agenda, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/43/147/full/

-

Telemedicine Adoption and Prospects in Sub-Sahara Africa: A ..., accessed October 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11989057/

-

Telemedicine: Opportunities and developments in Member State ..., accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/telemedicine-opportunities-and-developments-member-state

-

Telehealth & Telemedicine Market Size, Growth Drivers & Restraints - MarketsandMarkets, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/telehealth-market-201868927.html

-

The Mobile Economy Africa 2025 - The Mobile Economy - GSMA, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-economy/africa/

-

Powering Progress through Connectivity: GSMA's Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa Report Calls for Action to Close the Digital Divide, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.gsma.com/newsroom/press-release/powering-progress-through-connectivity-gsmas-mobile-economy-sub-saharan-africa-report-calls-for-action-to-close-the-digital-dividenew-report-highlights-opportunities-in-ai-5g-and-satellite-connectivit/

-

Adoption of Digital Health Technologies in Sub-Saharan Africa - Didida, accessed October 27, 2025, https://didida-health.eu/adoption-of-digital-health-technologies-in-sub-saharan-africa/

-

GSMA signs agreement with Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, to harness the power of mobile to combat disease in Africa - Africa CDC, accessed October 27, 2025, https://africacdc.org/news-item/gsma-signs-agreement-with-africa-centres-for-disease-control-and-prevention-to-harness-the-power-of-mobile-to-combat-disease-in-africa/

-

Digital Transformation Drives Development in Africa - World Bank, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2024/01/18/digital-transformation-drives-development-in-afe-afw-africa

-

Accelerating Digital Literacy to Benefit Education Systems in Africa | Mastercard Foundation, accessed October 27, 2025, https://mastercardfdn.org/en/articles/accelerating-digital-literacy-to-benefit-education-systems-in-africa/

-

africa human capital - heads of state summit - The World Bank, accessed October 27, 2025, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/3eb99d2c0a89888a7d1292898cce4651-0010012023/original/004-Digital-Skills-to-Accelerate-Human-Capital-for-Youth-in-Africa.pdf

-

Telehealth during COVID-19: why Sub-Saharan Africa is yet to log-in to virtual healthcare?, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.aimspress.com/article/doi/10.3934/medsci.2021006?viewType=HTML

-

(PDF) Telemedicine Adoption and Prospects in Sub-Sahara Africa: A Systematic Review with a Focus on South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria - ResearchGate, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390346452_Telemedicine_Adoption_and_Prospects_in_Sub-Sahara_Africa_A_Systematic_Review_with_a_Focus_on_South_Africa_Kenya_and_Nigeria

-

Healthtech Companies in Africa Were Founded in Droves Amidst the ..., accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.salientadvisory.com/insights/health-tech-companies-in-africa-were-founded-in-droves-amidst-the-pandemic-what-are-companies-doing-and-where/

-

Revolutionizing Digital Health in Rwanda: Progress Toward Universal Health Coverage, accessed October 27, 2025, https://digitalshowcase.lynchburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=jipa

-

Government of Rwanda, Babyl partner to provide digital healthcare to all Rwandans, accessed October 27, 2025, https://rdb.rw/government-of-rwanda-babyl-partner-to-provide-digital-healthcare-to-all-rwandans/

-

4 Healthcare Companies in Africa Leveraging Technology to Drive Innovative Solutions, accessed October 27, 2025, https://empowerafrica.com/4-healthcare-companies-in-africa-leveraging-technology-to-drive-innovative-solutions/

-

Zuri Care | Comprehensive & Affordable Healthcare Plans, accessed October 27, 2025, https://zuri.health/zuri-care

-

online medical consultation: a day in the life of a zuri patient, accessed October 27, 2025, https://zuri.health/blog/online-medical-consultation-a-day-in-the-life-of-a-zuri-patient

-

Online Healthcare Software | Vezeeta's Smart Health Solution, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.cmarix.com/vezeeta-online-healthcare-software.html

-

DRO Health - Apps on Google Play, accessed October 27, 2025, https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.seadvocacy.docsrchout

-

DRO Health | EMR, Telemedicine & Wellness Solutions in Nigeria, accessed October 27, 2025, https://drohealth.com/

-

mHealth Ecosystem Partnership - GSMA, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/mhealth-ecosystem-partnership/

-

Digitization Directorate General (DDG) - MOH-Rwanda, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.moh.gov.rw/digitization-directorate-general-ddg

-

Expert advice from a doctor | Hello Doctor | Momentum Healthcare, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.momentum.co.za/momentum/personal/medical-aid/hello-doctor

-

Hello Doctor - Home, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.hellodoctor.co.za/

-

East African trailblazers in telemedicine boost healthcare access - World Health Expo, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.worldhealthexpo.com/insights/telemedicine/east-african-trailblazers-in-telemedicine-boost-healthcare-access

-

Find a Doctor Online | Book Trusted Medical Consultations - Zuri Health, accessed October 27, 2025, https://zuri.health/doctor-at-home

-

Babylon Health - Wikipedia, accessed October 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylon_Health

-

Vezeeta - Products, Applications, Solutions, Service - HealthTech Alpha, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.healthtechalpha.com/venture/vezeeta/product

-

Vezeeta For Doctors - Apps on Google Play, accessed October 27, 2025, https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.drbridge.Doctors

-

What is mPharma's business model? - Vizologi, accessed October 27, 2025, https://vizologi.com/business-strategy-canvas/mpharma-business-model-canvas/

-

mPharma, accessed October 27, 2025, https://mpharma.com/

-

Hello Doctor+ - Student Healthcare, accessed October 27, 2025, https://studenthealthcare.co.za/local/lifestyle-benefits/hello-doctor

-

Telehealth around the world - DLA Piper Intelligence, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.dlapiperintelligence.com/telehealth/countries/handbook.pdf?c=ZA

-

IBA Healthcare and Life Sciences Law Committee Telemedicine Survey – SOUTH AFRICA, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.ibanet.org/document?id=Healthcare-Telemedicine-Survey-South-Africa

-

TELEMEDICINE PRACTICE IN NIGERIA: NAVIGATING ..., accessed October 27, 2025, https://chambers.com/articles/telemedicine-practice-in-nigeria-navigating-compliance-data-protection-and-licensing

-

chambers.com, accessed October 27, 2025, https://chambers.com/articles/telemedicine-practice-in-nigeria-navigating-compliance-data-protection-and-licensing#:~:text=Section%2027%20of%20the%20NHA,personal%20data%20of%20a%20patient.&text=The%20Code%20expressly%20recognizes%20telemedicine,transfer%20of%20patients'%20personal%20data.

-

39—county E-Health Bill, cover, 2021 - Parliament of Kenya, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.parliament.go.ke/sites/default/files/2022-02/The%20County%20E-Health%20Bill%2C%202021.pdf

-

Rwanda 2025 Healthcare Law: Reform, Rights & Risk Lines, accessed October 27, 2025, https://stabitadvocates.com/legal-news/rwanda-2025-healthcare-law-reform/

-

Vital Strategies Shares Examples of How to Use Social Marketing to ..., accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.vitalstrategies.org/vital-strategies-shares-examples-of-how-to-use-social-marketing-to-benefit-public-health/

-

Best Telemedicine App for Doctors in Africa 2025 - Yapita Health, accessed October 27, 2025, https://yapitahealth.com/en/blog/articles/telemedicine-apps-in-africa-for-doctors

-

A New Digital Health Platform for Africa – Africa CDC, accessed October 27, 2025, https://africacdc.org/news-item/a-new-digital-health-platform-for-africa/

-

The governance of private sector engagement in health in the African Region: a descriptive case study, accessed October 27, 2025, https://joghep.scholasticahq.com/article/129034

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0