How to Know If Your Medical or Healthcare Startup Is Truly Worth Your Time, Energy, Resources, and Money

Most healthcare startups fail—not because the tech is bad, but because they solve the wrong problem. This in-depth guide shows founders how to decide if their medical or health-tech startup is truly worth their time, energy, resources, and money, and when they can be confident they’re attacking a problem that really matters, with special focus on Africa’s healthcare reality.

Abstract

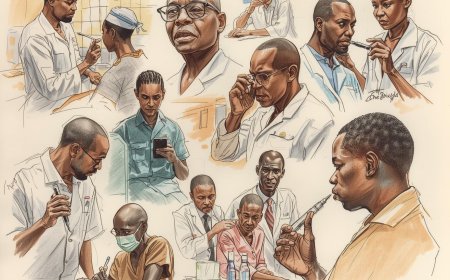

Around the world—and especially across Africa—healthcare is under intense pressure from workforce shortages, rising disease burdens, and chronic underfunding. Africa carries roughly 24–25% of the global disease burden but only about 3% of the global health workforce, creating fertile ground for innovation but also a brutal selection environment for weak ideas. Medical and digital health startups are emerging to fill gaps in access, quality, and efficiency, and the African digital health market alone is valued at around USD 3.4–3.8 billion, projected to grow at more than 15–23% annually through 2030.

Yet most startups in healthcare still fail, not only for lack of capital or technology, but because they do not solve a problem that is truly important to enough people who can and will pay—or at least sustain—the solution. For founders, clinicians, and investors, the central question becomes: How do you know if your medical or healthcare startup is really worth your time, energy, resources, and money? And closely linked: When can you feel confident that you are solving a worthwhile problem, not just building a clever but irrelevant product?

This paper synthesizes secondary research on healthcare innovation, digital health, startup success factors, and African health system realities. It provides a practical, structured framework to help founders and teams evaluate whether their startup idea merits serious commitment. The framework covers:

-

What makes a healthcare problem “worthwhile” (clinical, economic, and social dimensions).

-

Unique constraints of health and medical startups, including regulation, evidence, and ethics.

-

A four-lens evaluation model—Desirability, Feasibility, Viability, and Health Impact & Equity.

-

Specific signals that your idea is (or isn’t) worth the sacrifice, with examples from African health-tech ecosystems.

-

Practical tools: problem interviews, experiments, metrics, and checklists tailored to healthcare and African markets.

While the discussion is global, it repeatedly returns to Africa, where the combination of deep need and fragile systems raises the stakes of entrepreneurial choices. The paper argues that a healthcare startup is truly worth your effort when:

-

It targets a large, urgent, and repeatedly experienced problem,

-

For clearly identifiable stakeholders who are ready to change behaviour or spending,

-

In a way that is clinically safe and operationally realistic,

-

With a plausible path to economic sustainability and measurable health impact,

-

And where you, as founders, have authentic problem–founder fit—not just a passing interest.

1. Introduction

Healthcare is not like e-commerce or social media. It deals in pain, risk, trust, and life-or-death trade-offs. Mistakes have moral weight, regulations are strict, and adoption is slower because providers and patients are understandably risk-averse.

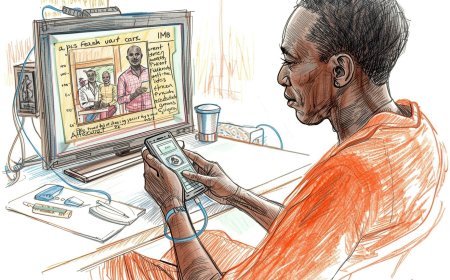

At the same time, the opportunity—and moral responsibility—for innovation is enormous. Sub-Saharan Africa’s health systems struggle with constrained budgets, workforce shortages, and infrastructural gaps. Yet mobile penetration, digital payments, and a young, tech-savvy population have sparked a wave of health-tech startups: telemedicine platforms, e-pharmacies, AI diagnostics, logistics for blood and vaccines, and more.

In this environment, many people are asking:

-

Should I start a healthcare startup now?

-

Is this problem I see at the clinic or in my community worth building a venture around?

-

Is it worth leaving my clinical job, my government post, or my stable salary?

This paper is written for such founders, clinicians, and early-stage teams. It does not tell you what to build, but helps you decide whether your idea deserves serious commitment. Using secondary research and a structured lens, we try to answer two deeply personal but practical questions:

-

How do you tell your medical or healthcare startup is worth your time, energy, resources, and money?

-

When do you feel confident you are solving a worthwhile problem?

We first clarify what “worthwhile” even means in a healthcare context, then build a framework to assess your idea, and finally translate this into concrete steps and checklists you can use immediately.

2. What Makes a Problem “Worthwhile” in Healthcare?

2.1 Beyond “Cool Tech”

In many startup ecosystems, there is a bias toward solution-first thinking: a novel AI algorithm, a clever mobile app, or a hardware device, followed by a frantic search for a use case. In healthcare, this approach is especially dangerous. Evidence shows that many e-health and digital health projects fail not because the technology is weak, but because they are poorly aligned with real provider workflows, patient needs, and health system priorities.

A “worthwhile” problem, for a healthcare startup, must satisfy at least four conditions:

-

Clinically Meaningful

-

Does solving this problem significantly reduce mortality, morbidity, or suffering?

-

Or does it meaningfully reduce burden on an already overstretched workforce (e.g., administrative load for nurses and doctors)?

-

-

Systemically Relevant

-

Is this problem recognized by health system actors—ministries of health, major hospitals, insurers, donors—as a priority?

-

Does it align with key strategies such as Universal Health Coverage and the WHO Global Strategy on Digital Health?

-

-

Economically Material

-

Is the problem associated with significant costs, inefficiencies, or revenue loss for a clearly identifiable payer (government, insurer, providers, patients)?

-

Can your solution capture some of that value in a sustainable business model?

-

-

Emotionally Salient

-

Do the people affected (patients, clinicians, managers) feel strong enough pain or frustration that they are willing to change behaviour and adopt a new solution?

-

In other words, a worthwhile problem is not just interesting; it is urgent, expensive, and painful to the right people.

2.2 Painkiller vs. Vitamin (But in Healthcare Terms)

In startup language, founders are often told to build “painkillers, not vitamins.” In healthcare, the analogy is literal:

-

Vitamins – solutions that are “nice to have,” improving convenience or adding marginal benefits, such as yet another wellness tracker app that does not integrate into clinical workflows.

-

Painkillers – solutions that address acute or chronic pain points like lack of access to doctors, stockouts of essential medicines, or unsafe medical records.

However, healthcare also values preventive interventions that are not always felt as urgent by individuals today, such as hypertension screening or adherence support for chronic conditions. WHO and CDC digital health strategies explicitly emphasize prevention, data, and system-level strengthening as core goals.

So, in healthcare, “worthwhile” may include:

-

Acute painkillers – e.g., remote triage that safely decongests emergency departments.

-

Chronic painkillers – e.g., better management of diabetes or sickle-cell disease.

-

Preventive and system painkillers – e.g., vaccination reminders, workforce scheduling, supply chain optimization.

The key is that someone—a payer, patient, or provider—feels the risk or cost strongly enough to care.

3. The Healthcare Startup Context: Why the Bar Is Different

Before assessing whether your idea is “worth it,” you must understand why the bar for healthcare startups is higher than for many other sectors.

3.1 Regulation, Safety, and Evidence

Health interventions can harm as well as help. Therefore:

-

Many countries classify certain digital health tools (e.g., diagnostics, decision-support algorithms) as medical devices requiring regulatory approval.

-

Payers and providers demand evidence—clinical studies, pilots, regulatory clearances—before broad adoption. It is not enough to “move fast and break things.”

For African founders, regulations may be less clearly defined but are rapidly evolving, especially as regional bodies respond to data protection, telemedicine, and cross-border services.

Implication: A problem is only “worth it” if you can realistically meet the regulatory and evidence expectations for your target market.

3.2 Fragmented Markets and Complex Payers

Unlike direct-to-consumer apps, healthcare startups must navigate multiple overlapping stakeholders:

-

Patients and families

-

Clinicians and hospital managers

-

Insurers and employers

-

Government programs and donors

In Africa’s mixed public–private systems, the payer is often not the patient. Public facilities may be free at the point of care; donors may finance specific programs; national health insurance may cover limited services.

Implication: A problem can be clinically important, but not “worth it” as a startup if you cannot find a workable payer or business model around it.

3.3 Risk-Averse Adoption

Healthcare organizations are generally risk-averse. Decision-makers prefer proven vendors and technologies, which makes it difficult for startups—even with better solutions—to gain traction.

This is intensified in African settings where infrastructure is fragile and budgets limited: a hospital cannot afford a failed IT implementation or a device that breaks in six months.

Implication: A problem is more “worth it” if the path to early adopters is clear—perhaps through smaller, agile private clinics, NGOs, or mission hospitals before large government systems.

4. A Framework for Evaluating Whether Your Startup Is “Worth It”

To decide if your startup idea deserves your time, energy, resources, and money, it helps to use a structured framework. Building on innovation and healthcare literature, we can adapt four lenses:

-

Desirability – Do key stakeholders truly want this problem solved this way?

-

Feasibility – Can we build and deliver a safe, reliable, compliant solution?

-

Viability – Is there a sustainable business model?

-

Health Impact & Equity – Will this meaningfully improve health outcomes and fairness?

These map loosely onto widely used innovation frameworks and healthcare-specific models that highlight the need to align technical possibility, user demand, and system incentives.

4.1 Desirability: Does Anyone Truly Care Enough?

Ask yourself:

-

Who wakes up already worried about this problem?

-

How often do they experience it?

-

What workarounds are they using today?

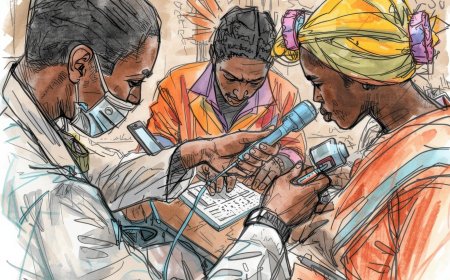

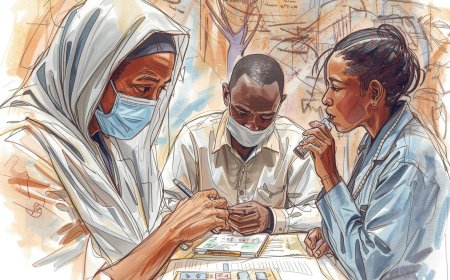

For example, African health workers frequently juggle paper records, stockouts, and multiple parallel data systems due to donor reporting requirements. These are not abstract annoyances—they cost time, lead to medication errors, and frustrate staff.

Strong indicators of desirability include:

-

Stakeholders bring up the problem unprompted in interviews.

-

They can quantify the pain (e.g., “We lose one day a week to paperwork,” “We run out of insulin every month”).

-

They have tried to hack solutions themselves: WhatsApp groups, shared spreadsheets, offline dashboards.

If, after dozens of conversations, people respond with polite interest but no urgency, the problem is unlikely to be worth betting your life on.

4.2 Feasibility: Can You Safely and Legally Deliver?

In healthcare, feasibility is not just technical; it includes:

-

Regulatory feasibility – Can you comply with device and data protection regulations?

-

Clinical feasibility – Do you have credible clinical oversight and pathways to test safety and efficacy?

-

Operational feasibility – Can your solution work with unreliable electricity, intermittent internet, and low digital literacy, which are common in many African contexts?

If your solution depends on perfect connectivity, expensive hardware, or specialist staff that simply do not exist in your target market, it may not be feasible—even if the problem is very real.

4.3 Viability: Who Pays, and Is the Math Realistic?

Healthcare startups can pursue several models:

-

B2G (business-to-government) – selling to ministries of health or national insurance schemes.

-

B2B (business-to-business) – selling to hospitals, labs, or insurers.

-

B2C (direct-to-consumer) – charging patients directly, often via mobile payments.

-

Donor or NGO-funded pilots – common in Africa, but risky as a sole source of revenue.

A problem is more “worth it” when:

-

There is a clear payer with budget authority.

-

Your solution produces measurable cost savings or revenue uplift for that payer (e.g., fewer readmissions, lower stock wastage).

-

Unit economics can work at realistic price points and adoption rates.

Early-stage donors or grants can be excellent catalysts but should not be the only path to viability; many African health startups struggle when grant cycles end and no payer steps in.

4.4 Health Impact & Equity: Are You Making Health Better and Fairer?

Unlike many other sectors, healthcare carries an ethical obligation: first, do no harm. But there is also an opportunity: to advance equity—to ensure that digital health and innovation do not exacerbate existing inequalities. WHO’s Global Strategy on Digital Health explicitly emphasizes equity, accessibility, and alignment with national health goals.

Questions to ask:

-

Does this solution improve access for rural, low-income, or marginalized groups—or only for urban elites with smartphones and private insurance?

-

Could it unintentionally widen disparities (e.g., by diverting scarce clinicians into lucrative tele-consulting for wealthy clients only)?

-

Are you collecting data ethically, with informed consent and robust safeguards?

A problem is more “worthwhile” when solving it contributes not only to profit but to better, fairer health outcomes, particularly in regions like Africa where inequities are pronounced.

5. When Is a Healthcare Startup Worth Your Time, Energy, Resources, and Money?

Now we connect the framework to your personal decision: Should you, personally, invest years of your life and a significant share of your savings or reputation into this venture?

5.1 Founder–Problem Fit

“Founder–market fit” gets a lot of attention. In healthcare, you also need founder–problem fit:

-

Lived experience – Have you experienced this problem as a clinician, patient, caregiver, or administrator?

-

Access to the field – Can you easily talk to stakeholders, visit sites, and observe workflows?

-

Motivation – Does this problem connect to your values enough to keep you going through regulatory delays, pilot failures, and funding rejections?

Interviews with African health founders show that those addressing problems they personally experienced in clinics or communities are more resilient and better able to navigate complex health systems than those chasing abstract trends.

If you are only mildly interested in the problem, but mostly excited about “doing a startup” or “using AI,” that is a warning sign. The healthcare journey is too hard to sustain on weak motivation.

5.2 Opportunity Cost and Time Horizon

Healthcare startups typically have:

-

Longer sales cycles (months to years),

-

Higher evidence requirements, and

-

Slower, more gradual scaling curves than consumer tech.

Ask:

-

Can you afford 3–5 years of sustained effort before seeing large scale or exits?

-

What are you giving up—clinical practice, academic careers, stable government posts, family time—and is the potential impact and upside worth it to you?

Your startup is more “worth it” when you have explicitly weighed these trade-offs and still feel convinced.

5.3 Personal Risk and Ethical Comfort

In health, ethical questions surface quickly:

-

Are you comfortable deploying a tool that influences clinical decisions?

-

Do you have adequate indemnity, governance, and clinical oversight?

-

Are patients’ rights and privacy robustly protected?

If you constantly feel uneasy that your solution might cause harm or mislead vulnerable users—and cannot mitigate that risk—then the venture may not be worth your personal reputation and conscience.

6. When Can You Feel Confident You Are Solving a Worthwhile Problem?

True confidence is never absolute; healthcare is messy and uncertain. But there are signals that your problem is worthwhile enough to justify deep commitment.

6.1 Signal 1: Strong, Repeated Problem Validation

You have spent significant time listening before building:

-

Conducted dozens of problem interviews with clinicians, patients, managers, and payers.

-

Heard the same pain points over and over, in different words, across different facilities or countries.

-

Seen stakeholders emotionally react when describing the problem (frustration, anger, shame, or exhaustion).

Qualitative research in healthcare innovation emphasizes that deep understanding of workflows and context is a critical success factor, especially for digital health tools.

If you have not done this work yet, any sense of “confidence” is premature.

6.2 Signal 2: Stakeholders Try to Pull You In

You know you’re onto something when potential users start pulling the idea out of you, rather than you pushing it on them:

-

Clinicians offer to pilot your idea, even in rough form.

-

Hospital managers ask, “When can we try this?” or “Can you also solve X related problem?”

-

NGOs or government officials say, “This aligns with our program; let’s explore a pilot.”

In African health-tech stories, some of the most successful startups (e.g., logistics platforms for blood and medical supplies, telemedicine services integrated into insurers’ offerings) grew initially because partners kept asking them to expand into new sites or services.

If, instead, stakeholders consistently say, “Interesting… maybe later,” and no one actually offers time, data, or a pilot site, your problem may not be as burning as you think.

6.3 Signal 3: Early Behaviour Change, Not Just Praise

Healthcare professionals are polite. They will often say your idea is “good” or “important” even if they never plan to use it. The real test is behaviour change:

-

Do clinicians actually log into your tool regularly?

-

Do patients return for repeat use (tele-consultations, refills, adherence tracking)?

-

Do partners renew pilot agreements, expand, or allocate budget?

Research on digital health pilots in Africa highlights that many projects die after the pilot phase because they rely on donor-funded enthusiasm rather than sustained behaviour change and integration into routine workflows.

Early, modest but real behaviour change is a more reliable sign than enthusiastic quotes.

6.4 Signal 4: Emerging Evidence of Health or Economic Outcomes

As you mature, you should see signals of actual impact:

-

Reduced waiting times, fewer stockouts, better adherence, or improved health indicators.

-

Lower costs per patient, fewer unnecessary visits, or reduced readmissions.

Even small-scale case studies or observational data can be powerful, especially when they resonate with global priorities such as improving primary care, strengthening health workforces, and accelerating digital health transformation.

If, after pilots, you cannot show any plausible improvements, you may not be solving a truly important problem, or your solution may not be the right approach.

6.5 Signal 5: Alignment With Macro Trends and Policies

Your problem will feel more “worthwhile” when it sits at the intersection of micro pain points (clinic level) and macro priorities (policy level):

-

Does it support national strategies for Universal Health Coverage, digital health, or primary care?

-

Does it tap into growing markets such as Africa’s rapidly expanding digital health sector?

This alignment increases the odds of attracting supportive partners, funding, and favourable regulations.

7. Practical Tools: How to Test Whether Your Problem Is Worthwhile

Theory is useful, but founders need concrete steps. This section offers tools to de-risk your decision.

7.1 Step 1: Structured Problem-Space Research

Before you design screens or write code:

-

Stakeholder Mapping

-

List all affected parties: patients, nurses, doctors, pharmacists, lab staff, administrators, insurers, government agencies.

-

Map who feels the problem most acutely and who controls budgets or policy.

-

-

Problem Interviews

-

Conduct at least 30–50 interviews across multiple sites (urban/rural, public/private).

-

Focus on stories: “Tell me about the last time this happened.”

-

Listen for frequency, severity, and existing workarounds.

-

-

Shadowing and Observation

-

Spend time in clinics, hospitals, pharmacies, or community outreach programs.

-

Watch how people actually work, not how they say they work.

-

-

Document Review

-

Read national health strategies, digital health plans, and disease-specific roadmaps to see whether your problem is recognized as a priority.

-

The aim is to emerge with a rich, contextual problem statement, not a vague “healthcare is broken” narrative.

7.2 Step 2: Problem Scoring Matrix

Create a simple matrix where you score your problem (1–5) on:

-

Clinical severity (impact on mortality/morbidity)

-

Frequency and reach (how many people, how often)

-

Economic impact (costs, inefficiencies)

-

Emotional salience (strength of frustration)

-

Policy alignment (fit with national or donor priorities)

For example, an African tele-ophthalmology idea targeting diabetic retinopathy screening might score:

-

High on clinical severity (blindness risk),

-

Moderate on frequency (prevalence varies by region),

-

High on economic impact (costs of blindness),

-

Moderate on emotional salience (less visible than acute emergencies),

-

Strong on policy alignment if integrated into NCD strategies.

If your total scores are consistently low, you may be in “nice to have” territory.

7.3 Step 3: Lean Experiments in Healthcare (Ethically!)

Rather than building a full product, run small, ethical experiments to test demand and feasibility:

-

Service experiments – e.g., manually coordinating tele-consults through WhatsApp and a spreadsheet before building a full platform.

-

Paper prototypes – showing clinicians mockups of workflows and asking them to walk through how they would use it.

-

Price tests – offering the service at different price points to see willingness to pay (where appropriate and ethical).

Remember: in healthcare, “move fast and break things” is not acceptable when safety is at stake. Experiments must respect privacy and clinical governance.

7.4 Step 4: Early Metrics That Matter

Track early indicators such as:

-

Engagement – active users, repeat sessions, time saved per task.

-

Health process indicators – vaccination completion, prescription adherence, follow-up visit rates.

-

Operational indicators – reduction in data entry duplication, fewer stockouts, lower waiting times.

Compare these against benchmarks or historical data where possible. Emerging improvements—even small—can give you justified confidence that your problem and solution are worth continuing to pursue.

8. Special Considerations for Africa and Other Resource-Constrained Settings

Given the user base and context, it is essential to zoom in on African realities.

8.1 Structural Constraints That Shape “Worthwhile”

Africa’s health systems face:

-

Severe workforce shortages (projected shortage of 6.1 million health workers by 2030).

-

High disease burden (around 25% of global diseases with only 3% of health workers).

-

Unequal distribution of services, particularly in rural areas.

These realities mean that “worthwhile” problems often focus on:

-

Extending reach – telemedicine, mHealth, community health worker tools.

-

Supporting overburdened staff – task shifting, automation of routine tasks, clinical decision support.

-

Strengthening systems – supply chain, information systems, workforce planning.

If your idea does not intersect with these pain points, it might still be interesting, but you should question whether it addresses the highest-value opportunities in the region.

8.2 Donor Influence and Sustainability

Donor funding plays a significant role in African health programs. This creates both opportunities and distortions:

-

Donors may fund innovative pilots in areas like HIV, TB, or maternal health.

-

However, projects often stall when donor funding ends unless they have institutional buy-in and a sustainable model.

A problem is more “worthwhile” when:

-

It aligns with donor priorities and has a path to long-term integration into government budgets or private payers.

-

You design from day one for post-donor sustainability.

8.3 Leapfrogging and Local Adaptation

African health startups sometimes benefit from leapfrogging: skipping legacy infrastructure and moving straight to mobile or cloud-based solutions.

But local adaptation is critical:

-

Offline capability and data-light designs are often non-negotiable.

-

Integration with existing paper processes or low-tech workflows can be more valuable than building from scratch.

Your solution is more “worthwhile” when it respects and extends local realities rather than ignoring them.

9. Common Red Flags: When Your Startup Is Probably Not Worth It

Some patterns, if you recognize them early, should prompt serious reconsideration:

-

Problem defined by buzzwords, not users – e.g., “We want to use AI/blockchain in healthcare,” with no clear, validated pain point.

-

Funding-first mentality – designing the startup around the latest grant call rather than a stable, long-term problem.

-

No clear payer – everyone agrees the problem is sad, but no one can or will pay to solve it.

-

Ignoring regulation and ethics – assuming that because regulation is “weak” you can skip clinical standards or data protection. This will eventually catch up with you, and can harm patients.

-

Purely urban-elite focus in a context where the greatest health burdens are rural and among the poor, unless your explicit strategy is to start there and then cross-subsidize other segments.

If several of these are true, you may still choose to experiment or learn—but think twice before staking your career and savings on the idea.

10. A Founder’s Checklist: Is This Worth My Time, Energy, Resources, and Money?

You can use the following as a “pre-commitment checklist”:

-

Problem Clarity

-

I can explain the problem in one sentence without mentioning my solution.

-

At least 30–50 stakeholders (across multiple sites) have confirmed they experience this problem frequently and painfully.

-

-

Stakeholder Buy-In

-

At least 3–5 clinicians, managers, or partners have offered to pilot, not just praise, the idea.

-

I know who the payer is and have had serious discussions with them.

-

-

Clinical and System Relevance

-

The problem affects core health outcomes or system performance (e.g., workforce, supply chain, data, access).

-

It aligns with at least one national or global health priority, such as digital health, primary care strengthening, or NCD control.

-

-

Feasibility

-

I have a realistic plan for regulatory compliance and clinical validation.

-

The solution can function in real-world African conditions (connectivity, infrastructure, staffing).

-

-

Early Traction and Metrics

-

In at least one pilot, I have seen actual usage and behaviour change, not just positive feedback.

-

There are early signs of health or operational improvements, even if small.

-

-

Personal Fit and Commitment

-

I have personal reasons—professional, ethical, emotional—that connect me to this problem.

-

I have honestly evaluated the opportunity cost and am prepared for a 3–5 year journey.

-

If you can tick most of these boxes with evidence, not just optimism, your startup is much more likely to be worth your time, energy, resources, and money—and more likely to be solving a genuinely worthwhile problem.

11. Conclusion

In medicine and healthcare, problem choice is ethics and strategy combined. When you decide which problem to build your startup around, you are not just placing a financial bet; you are choosing which patient stories, which frustrations, and which system failures will fill your next decade.

Secondary research on healthcare innovation, digital health strategy, and African health systems highlights that successful, impactful startups tend to:

-

Focus on deep, widely felt problems that matter to clinicians, patients, and payers.

-

Navigate regulation, evidence, and ethics thoughtfully, rather than treating them as afterthoughts.

-

Build models that are both financially viable and aligned with health equity, particularly in under-resourced regions like Africa.

Ultimately, your startup is worth it when:

-

The problem is clearly defined and repeatedly validated.

-

Stakeholders are willing to change behaviour and pay (or allocate budgets) to address it.

-

The solution is feasible within regulatory, clinical, and infrastructural constraints.

-

The business model is realistic, not dependent forever on grants.

-

The expected health impact and equity benefits justify the effort and risk.

-

And you, personally, feel that spending years of your life on this is not just a clever career move but a meaningful contribution.

You will never have 100% certainty. But by using the frameworks, questions, and tools outlined in this paper—and by grounding your choices in both data and lived reality—you can move from vague hope to informed conviction that your medical or healthcare startup is genuinely worth your time, energy, resources, and money, and that you are fighting a problem that truly deserves to be solved.

References

AfriQuire. (2025). The rise of health tech startups in Africa: A new era.afriquire.com

Arielle for Africa. (2025). The rise of healthtech in Africa: Startups transforming access, affordability and outcomes.arielleforafrica.com

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Global digital health strategy.CDC

Grand View Research. (2024). Africa digital health market size & trends.Grand View Research

IQVIA. (2024). Digital health system maturity in Africa (White paper).IQVIA

McKinsey & Company. (2024). Overcoming sub-Saharan Africa’s health workforce paradox.McKinsey & Company

Research and Markets. (2024). Africa digital health market insights, trends & growth analysis to 2030.Research and Markets

ScienceDirect. (2023). Critical success factors of startups in the e-health domain.ScienceDirect

The BMJ Global Health. (2022). Projected health workforce requirements and shortage for addressing the disease burden in the WHO African Region by 2030.bmj.com

The BMJ Global Health. (2022). The health workforce status in the WHO African Region: Findings of a cross-sectional study.bmj.com

The Lancet. (2023). Addressing the issue of a depleting health workforce in sub-Saharan Africa.The Lancet

The Research Insights. (2024). Africa digital health market 2024–2030.theresearchinsights.com

Villgro Africa. (2024). From obstacles to opportunities: How health startups are redefining Africa’s healthcare ecosystem.Villgro Africa

World Health Organization. (2020). Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025.

World Health Organization. (2025). Key findings of need-based health workforce requirements to address the disease burden in the WHO African Region by 2030 (Factsheet).files.aho.afro.who.int

World Health Organization. (2025). Global health workforce statistics database.World Health Organization

World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. (2025). The health workforce status in the WHO African Region.bmj.com

World Health Assembly. (2025). Resolution extending the global strategy on digital health to 2027.globalsante.org

FasterCapital. (2025). Healthcare startups: Challenges and solutions.FasterCapital

Forbes Technology Council. (2025). 20 hurdles for healthcare tech startups in scaling solutions.Forbes

MedTech Pioneers. (2024). 5 key factors to consider when building a healthtech startup.MedTech Pioneers

Bio-Focus. (2025). Overcoming startup challenges: Key strategies for healthcare.bio-focus.org

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0